To the pioneer settlers of Washtenaw County and Ann Arbor in 1829, a newspaper was much more than a chin-wag tabloid that told tales out of school about neighbors. What was needed was a publication for promoting the new community in order to draw more settlers and increase the village’s population. Hence the title of the weekly Western Emigrant, first published on November 18 of that year. In addition to passing important information to and from outlying towns, the county’s first newspaper carried business advertisements touting goods and services and was a vehicle where political news and personal views were voiced.

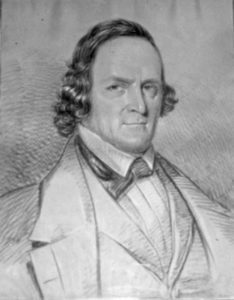

Thomas Simpson launched the Western Emigrant in 1829, but sold it after just five issues to two men with vested interests in the county’s growth: Ann Arbor cofounder John Allen (right), and Dexter founder Samuel Dexter (far right). Dexter soon became sole owner, and likely penned a two-page editorial urging “the possibility and necessity” of building a transcontinental railroad. | Photos courtesy of U-M Bentley Historical Library

First published on November 18, 1829, The Western Emigrant was the creation of Thomas Simpson. Simpson had zealous political opinions—he once drunkenly punched George W. Bullock square in the face because he thought that Bullock, a Whig, was about to disparage the Democratic party—but he kept them out of the Emigrant. The paper was looked upon as “neutral” in the respect that it made no claim to any political faction.

Below the masthead, Simpson stated that subscribers could pay $3 per year in advance, $3.50 at the end of the year, or in country produce, if delivered.

Typical of the journalism of that era, most of the four-page first issue consisted of articles previously published elsewhere: A piece on hemp was credited to the Western Tiller and one on tobacco exports to the Niles Weekly Register. A complete copy of the Declaration of Independence graced page one directly below the terms of subscription. As the only paper in the area, the Emigrant was also paid by the state to publish new territorial laws.

By Simpson’s fourth issue, dated December 16, the paper included advertisements promoting a tannery, a distillery, a school for young ladies and gentlemen, and Ann Arbor cofounder John Allen’s new mercantile store. But while the new publication was breathing life into the Ann Arbor business community, it apparently was not a paying proposition: Simpson published just one more edition, on December 23, where he introduced Allen and Dexter founder Samuel Dexter as the paper’s new owners.

—

They did not share Simpson’s professed political neutrality.

The Emigrant’s first issue under their new ownership carried a somewhat firebrand editorial endorsed by both Allen and Dexter, affirming in no uncertain terms that the newspaper would be a spirited voice against Freemasonry.

Though Allen himself had hosted Ann Arbor’s first Masonic meeting in 1824, like many Americans he had turned against the group after the 1826 kidnapping and disappearance of a New York man who had threatened to publish its secret rituals. Only a handful of convictions ensued, all for lesser offenses, and when it was revealed that witness tampering had occurred—and that some of the judges and jurors involved were Freemasons—many Americans became convinced a vast Masonic conspiracy was afoot.

With that editorial, eighty subscribers terminated their subscriptions. But the paper maintained its anti-Masonic position; apparently subscription income was not as important as its political tenets. The paper received support from the editor of the Middlebury Free Press, a Vermont newspaper, when on March 25, 1830, he wrote that “the Western Emigrant is a sterling anti-Masonic newspaper, edited with skill and talent.”

The same month, the Emigrant added a freelance Washington correspondent: Ebenezer Reed, a previous owner of the Detroit Gazette, now employed there by General Duff Green’s proto news service, the United States Telegraph. Despite the name, the Telegraph was still in its cradle—Reed delivered his column via U.S. Mail.

“I like it well,” he wrote to Allen and Dexter, of the Emigrant “—the only fault I find is, that it has too much anti-Masonry—one column a week is enough in all conscience. Too much of any one thing is sure to beget satiety, whether exhibited to the mental or physical appetite.” His criticism fell on deaf ears; the paper continued its anti-Masonic tirades until the fervor subsided several years later.

Allen and Dexter didn’t limit themselves to anti-Masonry. They also made the Emigrant an organ for the temperance movement, while acknowledging that it sometimes conflicted with their promotional agenda. When the paper featured Anthony Doolittle’s announcement on the innovation of a new distilling process, they explained in an editorial: “We are decidedly opposed to the practice of converting corn or any other kind of grain, into the liquid poison (called whiskey), yet, so far as this discovery tends to the advancement of the arts and sciences, we wish it success.”

—

Delivering the Emigrant was no small task. The papers were bundled and sent via the post to consignees, who would then deliver them in their area. Roswell Root, who served as postmaster for the now-defunct town of Borodino in Wayne County, reported that a package of Emigrants had been delivered addressed to a William Packard, but no person was there with that name. Often, a number of subscribers wrote Allen stating they had not received their paper.

In the May 19, 1830, edition of the Emigrant, it was announced that George Corselius would officially take over as editor. But other changes were on the horizon. A notice in the June 23 issue stated that Allen was turning all his interest in the Western Emigrant over to Dexter.

Under Dexter’s sole ownership, the newspaper’s circulation area grew as far as Oakland (Pontiac), Monroe, and Adrian. With this growth, the Emigrant advertised for an apprentice a number of times. It must have eventually found one, because three months following the final advertisement, the Emigrant shared the news that its apprentice, Mark Howard, had lost an eye due to a Fourth of July fireworks mishap.

With the start of volume II on November 24, 1830, the title of the Western Emigrant was officially truncated to The Emigrant. The anti-Mason editorials faded away, as did the party after Andrew Jackson’s reelection as president in 1831. The paper now aligned with the Whigs, who opposed efforts by Jackson’s Democratic Party to strengthen the executive branch. But the paper’s pro-temperance stance remained just as dogged as ever.

The Emigrant remained a cheerleader for progress, especially insofar as it might benefit the local community. On February 8, 1832, a page-two editorial entitled “Something New” strongly urged “the possibility and necessity of the [transcontinental rail] road.” The anonymous writer, most likely Samuel Dexter, hoped to see Michigan served by such a railroad. That wish was fulfilled in 1839 when the Michigan Central Railroad linked Ann Arbor to Detroit, reaching Dexter two years later.

In December 1834, the Emigrant was renamed the Michigan Whig. A policy statement confirmed its commitment to the party’s positions, which saw Congress as the rightful center of national power.

By then, the ambitions of its town-founder owners were well on their way to being realized: Between the censuses of 1830 and 1840, the county’s population grew nearly six-fold, from 4,042 to 23,571.