“Their lives are characterized by travel, hard work and a richness of experience uncommon to the average American.”

—Dylan Strzynski

Helen Gotlib and one of her nature-inspired prints. (All photos courtesy of the artists.)

Growing up in Ann Arbor, Helen Gotlib loved the art fair. Even as a little kid, “I thought it was super cool,” she says. “I thought, ‘maybe one day I can be in this.’ ”

She studied printmaking and scientific illustration at the U-M, but once she graduated in 2003, she was on her own.

“Art academia sometimes suggests that showing work in Europe and having that long list of museum and gallery shows and openings is what matters,” says Gotlib. But there was no clear pathway for a newly minted BFA to do that. “There were no answers as to how to make a living.

“That’s the fallacy of art school,” she says. “Nobody said, ‘You should be in galleries,’ or ‘You should do this.’ It was just ‘You should go to grad school and figure that out.’ ”

She was selling her work at the Sunday Artisans Market when one of her teachers suggested she try art fairs. So she and her fellow artist and life partner, Dylan Strzynski, joined the circuit. Attending as many as sixteen shows a year, they traveled the country, “staying at other artists’ houses, going camping with them, checking out national parks with them, going to museums with them.

“We’re doing all of these shared experiences. It’s so much more than just going to the art fair.”

That’s also the message of The Life We Make, a documentary by Strzynski and independent filmmaker Padrick Ritch. “The whole time when Dylan and I were doing our shows all over the country, he was always filming,” Gotlib recalls. There are scenes of artists in their homes and studios, on the road, at fairs, framing an artwork on an unmade bed in a hotel room—“just all these little snippets of life,” Gotlib says.

Strzynski and Ritch are currently showing The Life We Make at film festivals. Meanwhile, the direct experience comes to Ann Arbor July 21–23, when hundreds of artists and thousands of art lovers descend on Ann Arbor’s downtown.

Here are some of their stories.

William Kwamena-Poh’s detailed, realistic watercolors depict the world of Ghana’s traditional fishermen. There’s more to it than fish and boats. “The fishermen have children, and they have wives, and they take their fish to market, and so that is how my story is told,” he says.

William Kwamena-Poh paints in his Savannah studio. (All photos courtesy of the artists.)

Born in Ghana, Kwamena-Poh has lived in Savannah, Georgia, for many years and has sold his work at Ann Arbor’s State Street District Art Fair since 1994. One reason he chose it is because he’s allowed to sell prints of his work.

“I focus on making sure that the average person, especially people of color, who have never had that kind of financial wealth, are able to buy pieces,” he explains.

Kwamena-Poh likes being able to “go around, show your work, and get a response for it. You grow, because there’s always a challenge: If you’re going to do art shows, that means you have to keep producing, year after year, all the time.”

As a black man, “it’s difficult driving across country, with all this animosity,” he adds. “I’ve been stopped a few times, but at the end of the day, I know how to act.” Still, he hopes that he doesn’t meet the wrong cop. “What if one says, regardless of what you say, you’re wrong?”

The pandemic shutdowns “affected me really hard,” Kwamena-Poh says, but “I’ve been blessed, and I’ll be OK.

“Right now, I have my health. Let me work as hard as I can. Let me be as creative and productive as I can. I’m sixty-two … but you do your work just as hard as you always did, until your body tells you otherwise …

“As an art fair artist, you have to have faith—because you never know if your work is going to sell.”

In March 2020, Gotlib and Strzynski did a show in Florida. Then Covid hit. The show the following weekend was canceled—and then the one after that. They wouldn’t do another for fifteen months.

Yet people still wanted art. Gotlib makes mixed-media pieces inspired by nature, and “all of a sudden, I had collectors buying things off my website,” she recalls. “And the gallery I work with on the west side of the state, they were having their best year ever and selling work of mine.

When the fairs resumed, “last year was insane,” Gotlib says. “Every show we went to, in every city, it was the first time the people there were getting out and going to a large event.

“Everyone was so happy to be out! And sales were up. It was my best year by far.”

This July, Gotlib will have a single booth in the Ann Arbor Street Art Fair, the Original. Strzynski is “working on a new body of sculptural work, and so he’s taking the year off of shows to get that work ready for next year’s show,” she says.

“When you’re selling art to make a living, you’re not just an artist. You are a business person, too,” Gotlib points out. Everyone who purchases a piece goes on her mailing list, and “I’ll post on social media before the show, saying, ‘Hey, the show’s coming up, hope to see you down here’ and post some pictures.”

She still loves the fair experience. “It’s like this family of people,” she says. “It’s always moving and changing, [but] every show you go to, all over the country, you’re seeing your friends from different places, and there’s so much camaraderie.”

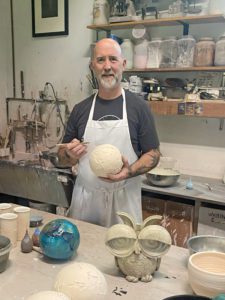

This will be Stan Baker’s forty-fourth fair—and he’s hoping his ninety-nine-and-a-half-year-old mentor, J. T. Abernathy, will stop by. (All photos courtesy of the artists.)

Potter Stan Baker is not in the film, but he knows the fair artist’s life intimately.

“This will be my forty-fourth year at the art fair,” says Baker from his Ann Arbor studio. “When I started, I was the youngest person in the art fair.” He began making pots and buying clay from pottery guru J.T. Abernathy while still a student at Community High School. By sixteen, he knew that it “was my chosen path in life.”

In 1978, he graduated from high school, started apprenticing with Abernathy, joined the Guild of Artists & Artisans, and did his first Ann Arbor art fair “because that was a way to make money and sell my art.” He’s been with the Guild ever since, chairing its board for the last decade.

Baker says he’s made a “very good living. I have a nice house and all the amenities I want.” But “it’s still a tough life,” he says. Artists “never know whether we’re going to do a show or not,” because they have to re-apply every year. “It’s like you have to put in your resume thirty or forty times a year, every year, to see if you’re going to make money.

“Just this year I applied to a show, and submitted an image of this beautiful blue pottery that I made.” He got in, and the jurors “commented on how beautiful the work was, and that they loved the colors.

“Three years ago I got rejected from the very same show, with the very same image—they said it was outdated. So it went from being outdated to being extremely gorgeous in three years.”

During the pandemic, “I had zero income for eighteen months,” Baker says. Even with pandemic unemployment benefits, “I pretty much just used up a lot of my savings.”

Now in his sixties, he’s booked more than thirty fairs this year. This month, he’ll be back in the Guild fair on Main St. He’s hoping that J.T. Abernathy, now ninety-nine-and-a-half, will stop by.

When Joachim Knill watched The Life We Make for the first time, he thought, “Oh I look so goofy!” The second time, though, “I felt better about it. I really liked the movie. It’s a portrait of people.”

Dylan Strzynski shoots video for The Life We Make. “The whole time when Dylan and I were doing our shows all over the country, he was always filming,” Gotlib recalls. (All photos courtesy of the artists.)

Knill grew up in Switzerland and came to the U.S. with his family when he was seven. As a kid, he created a world with “all these stuffed animals,” making “maps where they lived and pictures of their houses—I even made portraits.”

That’s now come full circle. He describes his booth at the Ann Arbor Street Art Fair, the Original, as an “installation of a shipping crate containing a portrait room of oil paintings, stolen, acquired, and traded from some place inhabited by stuffed toy animals”—they’re the regal figures in the portraits.

The reaction at other art fairs, he says, “was kind of what I was looking for— ‘Oh, how cute!’ and ‘Oh, how creepy!’ ”

Joachim Knill says the response to his portraits of stuffed animals “was kind of what I was looking for—‘Oh, how cute!’ and ‘Oh, how creepy!’ ”

Knill, fifty-six, has a BFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and has been coming to the Original fair since 1994. He lives in Hannibal, Missouri, with artist Janice Ho.

They met at an art fair. In the film, Ho recalls that she was married at the time but “got unmarried,” asked Knill out, and “got him to hang out with me after that.” At the end of The Life We Make, the couple was expecting their first child.

The documentary took years to shoot and assemble, then was delayed by the pandemic: Knill reports that their son Idi is now eight, and daughter Zana will turn five this year.

“I had been considering taking a year off while our two kids are still young and needy, so the pandemic was a sort of welcomed forced sabbatical,” he emails. “I have been keeping plenty of savings for unforeseen down years,” and “pandemic unemployment assistance also was a big help.”

While the Ann Arbor fair used to be one of his best in terms of sales, it hasn’t been as lucrative lately. “It’s one of the shows I sometimes consider cutting,” he admits. “But then I think, ‘That’s home, and I go there every year … friends are there.’ ”

Though Ho won’t be showing her art this year, the whole family will travel to Ann Arbor with him. They’ll stay with Gotlib and Strzynski.

“We love going there because we get to visit Helen and Dylan,” says Knill. “Their house in the country feels like a vacation place.”

The 2022 Ann Arbor Art Fair runs Thursday, July 21, through Saturday, July 23.

Hours are 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Thurs. & Fri., and 10 a.m.–8 p.m Sat..

Parking in city structures is $18 per day, $9 after 5 p.m., and Park & Ride shuttles are available—see theannarborartfair.com/parking-shuttle for information.

Maps are available at fair information booths.

Performances on the Ingalls Mall Fountain, the Ark, and Ann Arbor Civic Theatre stages are listed under “Art Fair Entertainment” in the Observer’s daily Events listings—see p. 62.

Website for all three fairs: theannarborartfair.com.

The Ann Arbor Street Art Fair, the Original will include 193 artists from around the country, showing only original work. Director Angela Kline is new this year; former director Maureen Riley is helping with the transition as artist coordinator.

Centered on the U-M’s Ingalls Mall, the Original fair has arms on North University and E. Washington.

The Michigan Guild of Artists &Artisans Summer Art Fair expanded its footprint last year to encompass the former South University Art Fair. The new section on South U. from State to S. Forest (with some booths on East University) joins sections on S. Main, E. and W. Liberty, and State from William to Madison to showcase close to 400 artists in all. Guild executive director Karen Delhey emails, “we are really looking forward to more of a return to our normal activities this year.”

The State Street District Art Fair will have about 200 artists showing their work along Liberty, Maynard, E. William, and North U., while stores, restaurants, and crafters sell from tents on State.

The ongoing reconstruction of State St. will pause during the fair. Emails executive director Frances Todoro-Hargreaves, “we are … getting back to a pre-COVID atmosphere.”