For three decades the tower supporting the screen of the Ypsi-Ann Drive-In Theatre loomed over Washtenaw Ave. between Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, a monument to the days when Chevys had bench seats and In the Heat of the Night was more than just a movie.

The Ypsi-Ann operated only in the summertime until electric heaters were installed—and even then, a snowstorm sometimes canceled a showing. Valusek recalls that the heaters’ wiring sometimes generated a different kind of buzz.

Mention the Ypsi-Ann to anyone who came of age here in those years and you’re likely to get a knowing smile. Maybe even a story or two. But projectionist Al Valusek remembers it from a different vantage point: a squat little building planted in a field of speaker posts.

He started at the Ypsi-Ann in 1968, when the theater was twenty years old: It opened on May 29, 1948, with the Roy Rogers film Springtime in the Sierras. Early newspaper ads promised audiences a whole new way to watch movies. “Come As You Are—Smoke In Your Car,” said one. “No Parking Worries,” said another—there was space for 600 cars. And children of all ages were welcome: “Babies’ Bottles Warmed Free,” said a third.

In an indoor theater like the Michigan, the projectionist was isolated in a booth high above the audience. But a drive-in booth typically shared a modest building with the concession stand on the same level as the audience. A microphone allowed the projectionist to engage the people in every car—and unlike an indoor theater, each car came with a perfect device on the steering wheel for giving it right back.

Valusek used the microphone mainly to remind people to replace the speakers on their posts before driving away. But when I talked to Valusek recently, he recalled an exercise in drive-in democracy.

Because the show didn’t start until dusk, in midsummer his shifts began about 9:45 p.m. and often ran past 2 a.m. Even then it could be difficult to see the beginning of the first film of a double feature, so, at the end of the night, he was supposed to rerun the first forty minutes. However, one night, after showing Bullitt starring Steve McQueen, with its celebrated San Francisco car-chase sequence, he had another idea.

“I said, ‘I’m going to give you two choices, and you beep your horns for which one you want,” he recalls. “Now, how many of you want to see that first forty minutes [again]?’”

The response was the weak sound of a few horns.

“‘Now how many of you want to see the chase scene, with the cars and everything, instead?’”

Valusek imitated the sound of a chorus of horns.

“So that’s what we did.”

At intermission, he also sometimes earned a few appreciative honks with bawdier announcements such as this: “Would those of you who are going to come from the back of the field to the concession stand please make sure not to slip on the used rubbers?”

—

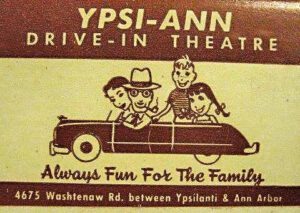

Free matchbooks reinforced advertisements that invited audiences to “Come As You Are—Smoke In Your Car.”

Since admission depended on the number of people in the car, some drivers would try to smuggle in additional passengers. Valusek remembers that “putting five or six people into the trunk of their car … was common.”

Hard to believe, but keep in mind that this was the era of bloated vehicles such as the Imperial LeBaron. Meanwhile, students were competing to see how many could wedge into a Volkswagen Beetle. (Depending on your source, the record is between seventeen and twenty.)

Like most theaters of its day, the Ypsi-Ann used thirty-five-millimeter film loaded onto twenty-minute reels. This required a pair of identical projectors. While the film was running on machine number one, Valusek would prepare the other by threading the next reel through a series of sprockets. Two minutes before the end of the reel, a bell would alert him to get ready for the “changeover.”

He’d turn on power to the lamp in machine number two, “strike” the lamp by touching two copper-clad carbon rods together, then back them off to create an intense “carbon-arc” beam. Next, he would move to the window next to that machine and watch for the first of two cues—usually dark circles—that would flash in the upper right corner of the screen.

“If you know what to look for, you’ll see it,” he says. “But people who watch movies generally don’t even know it unless it’s pointed out.”

On the first cue he would start the motor on projector number two and open a heavy damper that had been shielding the film from the heat of the lamp. On the second cue he would push a button on the front wall of the booth and a pedal on the floor that instantaneously switched the sound and picture from one machine to the other.

Thanks to such delicate choreography, “the projectionist job used to be a highly regarded, highly skilled job, handed down from father to son, and paid good money,” Valusek says.

In these years, local projectionists belonged to a union that assigned them to various indoor and outdoor theaters, often rotating between several in a year’s time. Valusek learned the ropes at the Ypsi-Ann from Peter Wilde, who was legendary for his knowledge of the art of film projection. Wilde’s innovative use of lighting and rear (behind-the-screen) projection also earned him jobs in the 1970s touring with bands such as KISS and Grand Funk Railroad.

Hubert (“my friends call me Hu”) Cohen, longtime U-M professor of film, television, and media, recalls inviting Wilde to talk to his classes about lighting and editing—“these wonderful little tricks that only a specialist … would understand and talk about. I can’t describe the value of that to me, and the influence it had on enlarging my understanding of film.”

—

The projectionists reminded drivers to replace their speakers because if they didn’t, they’d rip them from the posts when they drove away. Other drivers would simply toss them onto the ground, which caused a different problem.

The projectionists reminded drivers to replace their speakers because if they didn’t, they’d rip them from the posts when they drove away. Other drivers would simply toss them onto the ground, which caused a different problem.

“The plastic casing over the volume control would break, and that would leave an entrance to the speakers,” Valusek says. “And using that entrance wasps would fly in, and they would actually build nests there. … I don’t know if anyone ever got stung, but [drivers] were putting speakers inside the windows of their cars that had wasp nests with live wasps in them.”

To protect themselves, he says, before making repairs, “We would cut the speakers loose from the cords, and we would spray [them with] lighter fluid, and then we’d light them things up, and we’d toss them as far as we could real fast.”

At first the Ypsi-Ann closed in the winter, but by the time Valusek started, in-car electric heaters had been installed. They generated a different kind of buzz.

“Peter Wilde discovered that the field had been wired improperly, and those heaters could really [give] people a shock,” he says. “I think Peter mentioned it to somebody in the upper echelon of the company, and they said, ‘Yeah, we don’t have any money to [fix] that.’”

—

By the 1970s the concession stand had become a favorite target of burglars with a taste for cigarettes and ice-cream sandwiches. In August 1970 the Ann Arbor News reported that one thief “who apparently loves movies” had made off with 23,026 tickets and $100 cash from the front office.

When the Ypsi-Ann opened, that stretch of Washtenaw was a two-lane rural road. By the time Valusek started, however “housing projects [had been] dropped in on either side of it.” As development drove up property values, “it was obvious that that land was too valuable to be left alone as a drive-in.”

Starting in the 1970s, the spread of cable TV and the invention of the VCR encouraged more people to watch movies at home. In 1988, a Kentucky owner told the Los Angeles Times that he blamed the demise of drive-ins “solely on Daylight Saving Time.” (Congress adopt-ed DST nationwide in 1966; Michiganders voted to exempt the state in a 1968 referendum but reversed course four years later.) Others pointed to everything from the decline of the “car culture” to the rise of the “mall society.”

Meanwhile, the switch from carbon-arc to Xenon-bulb lamps and the development of projector platter systems—which involved splicing the whole film into one continuous strip—eliminated the need for twenty-minute changeovers and opened the door for multi-screen indoor theaters.

“The first multiple-screen theater in Ann Arbor was at the Briarwood [mall], and it was four screens at the time,” Valusek says. “And one person could handle all four when it was on a platter system. You just stopped and started [the films] at different times.” In 1973, he was among the first projectionists to work there.

The Ypsi-Ann, the first drive-in theater to open in the Ann Arbor–Ypsilanti area, was also the first to close. On December 12, 1978, an Ann Arbor News photo showed workers tearing down the iconic screen tower. Go to 4675 Washtenaw Ave. today and you’ll find the Glencoe Crossing shopping center.

—

This article has been edited since it was published in the June 2023 Ann Arbor Observer. Al Valusek’s first name has been corrected.

To the Observer,

Regretfully, I forgot to write you after seeing (and reading) the article about my friend Al Valusek. My twin brother Bob, briefly a fellow projectionist with Al in the ‘70s, called him “Floxie.” I’ve forgotten why, but that’s how I lovingly referred to him … and now seeing the correction of his name in the July Observer, I must tell you that Al died a few months ago. I have no details, only that he was in poor health and died at home, alone.

He was a wonderful person and friend: unique in every essence of the word, funny, brilliant, quirky, kind. Al was the shirtless (in the summer) thin man you’d see running or riding his bike up and down Newport Rd. pretty much day in and day out for years and years. His non-conventional appearance and running posture caused people to wonder, “Who the heck is that guy?”

Floxie collected and tinkered with stereo equipment, to the extent that he was seen as a hoarder. His modest house was filled to the brim with it, along with all kinds of electrical parts and equipment. For a while he had a side gig as a party deejay, putting his equipment to good use, as well as his fabulous taste in music and sense of humor.

So thank you for the article, for the reminder of what a great cinema town Ann Arbor once was, and for giving Al credit for his role in keeping the projectors running.

Sincerely,

Vicki Honeyman