A bird’s-eye view of the U-M campus in the early 1900s. Photograph courtesy of Bentley Historical Library

If one Googles “University of Michigan student riot,” two of the first three links point to the notorious 1908 Star Theater Riot. On that occasion, students, outraged at rumors that the theater owner had tried to bribe a football player to throw a game, demolished the theater, leading to sixty-five arrests. The other is to the 1969 South University riot, which an AADL page describes as “a series of confrontations between local law enforcement and factions of Ann Arbor’s counterculture population.”

Other links about those clashes reappear farther down Google’s list. But the search engine finds nothing about the worst conflict in the town’s history: the two-day melee in November 1890 that resulted in the death of one person and injuries to a number of others.

It started on the evening of November 11, when students lined up at the campus post office to get their mail. A bit of restless jostling led to a little pushing and shoving. In the eyes of the police, some students were becoming a bit too raucous. According to Ann Arbor Courier’s November 19, 1890 edition, a number of arrests were made. The evening ended with rumblings from the students percolating just below the surface.

On the following evening, students fired up by the arrests were milling around campus. According to the November 14, 1890, edition of the New York Times, everything seemed pretty quiet until about 9:30 p.m., when gunfire was heard.

The Courier later explained the shooting came from George Stoll’s wedding celebration: his fellow members of Company A of the state militia were giving him a military salute.

Though its members were volunteers, this was not the self-appointed “Michigan Militia” of recent years—it was an official branch of the state, the precursor to today’s Michigan National Guard.

Against orders, militiamen fired a salute at a member’s wedding, causing students to descend on the scene. In the melee, freshman Irving Dennison was hit on the head with a rifle butt; he died at University Hospital. Photograph courtesy of Bentley Historical Library

The militiamen had been told they could join the celebration, but without weapons. However, when a number of Stoll’s brothers-in-arms trooped to the wedding site at 9 p.m., they were carrying their rifles, loaded with blank cartridges, which they fired in celebration.

That volley drew students from campus. A Captain Armstrong, who was attending the ceremony, ordered his men to march to their armory, but an ever-growing body of jeering students followed. Enraged, quartermaster sergeant C. F. Granger ordered the militiamen to charge.

Standing on the sidelines observing the fracas was freshman Irving Dennison of Toledo. According to the Saline Observer, Dennison was struck on the head with a blunt object, possibly the butt of a rifle.

The Detroit Free Press reported that initially the injury did not appear to be that serious: Dennison was able to walk to the University Hospital on Catherine St., where he received stiches to close the wound over his eye.

But Dennison soon felt lightheaded and unwell. Upon further inspection, physicians discovered the side of his skull was crushed. Wood splinters in his brain confirmed that he’d been struck by a wooden gun butt. Dennison died at 5:05 the next morning.

With this tragic turn of events, the students became outraged. Fearing more violence, U-M president James Burrill Angell addressed Dennison’s death in a chapel ceremony, urging students to “be self-restrained,” according to a diary entry by law student Enoch Price. The Ann Arbor Courier reported that 1,500 students escorted Dennison’s remains to the Ann Arbor Railroad depot for his trip back home to Toledo, and a small contingent was chosen to attend the funeral.

—

The Saline Observer subsequently reported that the militiaman who struck Dennison incriminated himself while under the influence of whiskey, displaying Dennison’s watch and confessing to striking him. The man had purportedly hightailed it for Seattle, and a summons had been issued to bring him back to Ann Arbor. But his name was never given, and it appears that nothing further came of it.

According to the Neligh Leader’s November 20, 1890 edition, during the melee Sgt. Granger was also seriously injured. Struck in the head with a brick, he, too, suffered a fractured skull, and the paper gave only “even chances for his recovery.” Adding insult to injury, he was arraigned in his sickbed for his part in the fatal riot.

The Ann Arbor Courier criticized both the “boyish thoughtlessness” of the students and the “hot headed impetuosity” of the militiamen. But the Free Press opined that if the militiamen had not charged the students, they would have arrived at their armory without serious injury to either side.

The following May, the Columbus Daily Telegram stated that seven militiamen were arrested for the murder of Dennison, and Michigan

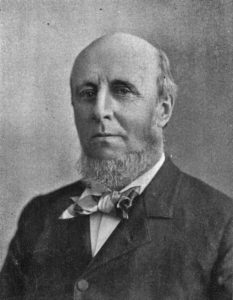

In the aftermath, U-M president James Burrill Angell (top) urged students to “be self-restrained,” while governor Edwin Winans (bottom) took away the company’s arms and ejected its members. Murder charges against seven militiamen were dropped for lack of evidence. Photographs courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

governor Edwin Winans had ordered the guard’s quartermaster general to take away Company A’s arms and equipment and to strike the names of its members from the state roster. But the same month, the Alma Record reported that the Washtenaw County prosecutor had dropped the charges against the militiamen, saying he lacked the evidence to convict anyone. Most students had left campus at the end of winter term in late April, leaving no witnesses to call.

—

As horrific as the 1890 riot was, it could have been worse. Had the militiamen’s rifles been loaded with live ammunition, many more students might have died.

The danger of wielding military weapons in mass protests was tragically demonstrated during the urban riots of the twentieth century, when hundreds were killed. But it took eighty years and another fatal campus protest to bring about systemic change.

At Kent State University in 1970, National Guardsmen fired on an antiwar protest, killing four and wounding nine. No state charges were filed, and though eight guardsmen were charged federally with violating the students’ civil rights, none were convicted.

According to Wikipedia, however, “In the years that followed, U.S. military and National Guard personnel began using less lethal means of dispersing demonstrators (such as rubber bullets), and changed its crowd control and riot tactics to attempt to avoid casualties amongst the demonstrators. Many of the crowd-control changes brought on by the Kent State events are used today by police and military forces in the United States when facing similar situations, such as the 1992 Los Angeles riots, and civil disorder during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.”

I hope this message makes it to Dave McCormick…Excellent article, The Forgotten Riot. I really enjoyed how you uncovered details from so many different and wide-reaching sources!