When he wrote the stories that would ruin his life, Emilio Gutierrez Soto had no concept of their significance. He didn’t realize they would set him on the grim path walked by journalistic martyrs who’ve risked everything for their profession, from Jamal Khashoggi to Marie Colvin to countless lesser-known compatriots of his in Mexico. He certainly didn’t expect they would transform him into an international symbol of press freedom in the age of Trump–or lead him to a new start in a university town in the distant north.

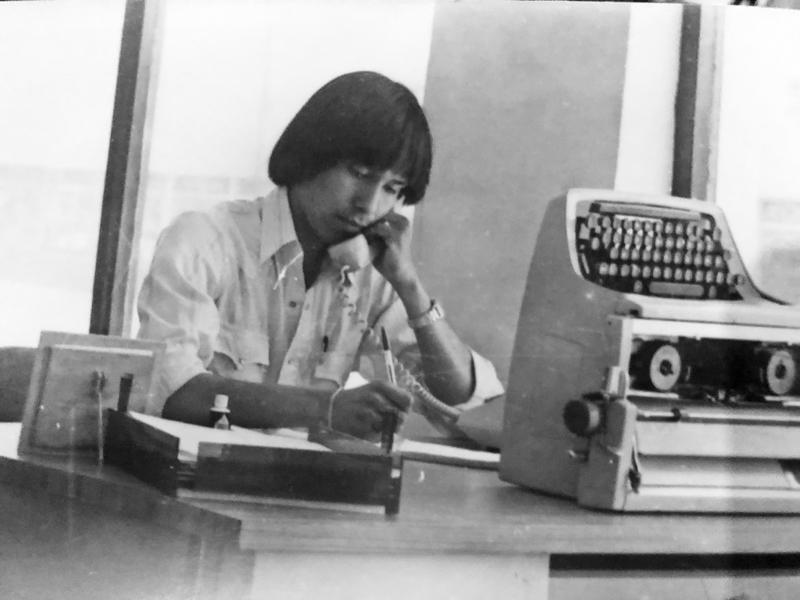

A reporter at a small newspaper in Ascension, a town of some 13,000 in the state of Chihuahua near the U.S. border, Gutierrez Soto covered local news, including crime and sports. In 2005, he wrote three articles on a series of assaults and robberies, and quoted victims who said the perpetrators were members of the military.

“When I wrote that, I was thinking of doing my duty at work,” he recalls in Spanish. “I did not think it would have these long and painful repercussions.”

He hadn’t expected to make powerful enemies. “If I had known,” he admits, “I would not have written it.”

He was summoned to a meeting with a Mexican general. Backed by a large group of soldiers, the general threatened to kill him because of his reporting and informed him that he was being placed under surveillance. The climate of fear grew worse in subsequent years, as the military’s role in fighting Mexico’s drug war expanded–along with attacks on the journalists who documented both sides’ abuses.

Gutierrez Soto filed complaints with the police and with Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission. He even published an article–without his byline–about the threats. But his actions only served to increase his peril, which culminated with a panicked late-night drive to the border in 2008 after he was warned of an impending plot to kill him.

He left everything but his then-teenage son Oscar behind. He hoped that they could start a new life in the U.S. “I thought I would meet with a nation that would be more humane, with laws that would be more flexible,” he says. He believed that, thanks to his “vastly credible reason that we had to leave everything behind in Mexico and ask for support and safety,” his case for asylum would be clear-cut. But his ordeal was far from over.

Gutierrez Soto and Oscar arrived legally in the U.S. in May 2008 and applied for asylum. They were immediately separated and detained in different facilities. They were only allowed to speak on the phone a few times over the two and a half months that Oscar was held before being released to live with some friends. Gutierrez Soto was not released until the following January, after President Obama’s inauguration.

Father and son spent nearly a decade in New Mexico, working odd jobs, operating a food truck, staying out of trouble–and attempting unsuccessfully to resolve their asylum case. But though those years were marked by growing support from the American journalistic and legal communities, it wasn’t the life Gutierrez Soto had planned. “I was making good money” in Mexico, he says. “I didn’t change that life to come here to wash dishes, to clean yards, to sell corn or ice cones–these are not denigrating jobs, but I did not change that to do this.”

But he knew his antagonists in Mexico hadn’t forgotten him, especially as his public profile–and his criticisms of his country’s government–grew. “The military is present in all institutions of power in Mexico–in the senate, congress, all secretariats, in all of them,” he says. “Mexico does not move if the military does not approve it–the military is everywhere!”

Even phone calls home came to seem risky. “After I requested political asylum, the telephones that my family members in Mexico had began to sound differently, with an echo,” he says. “So that made us think that they were being watched.” He decided the contact could put them in danger and cut off communication. Yet at least he was with his son. At least they were safe.

—

In July 2017, an El Paso immigration judge denied their asylum claim. The judge expressed doubts that Gutierrez Soto was in danger in Mexico and even questioned whether he actually was a journalist.

The decision and its timing, just six months after the inauguration of President Trump, sparked anger in journalist advocacy groups in the U.S. Many had come to support his long struggle for asylum and saw the decision as a reflection of the new administration’s animus toward both the press and immigrants.

While the judge’s decision was under appeal, the National Press Club invited Gutierrez Soto to accept its Press Freedom Award on behalf of journalists in Mexico. At the October 2017 event, he delivered a blistering, heartfelt speech attacking corruption in the Mexican government–and hypocrisy in the U.S. on the issues of human rights and freedom of the press.

A few weeks later, during a routine check-in with immigration, officials detained him and Oscar. Their wrists and ankles were cuffed and they were told they would be immediately deported, without waiting for the outcome of their pending appeal. His pro bono lawyer’s emergency intervention prevented that, but the two were put in a holding camp and left there for almost eight months.

“From the first to the last day it was like living in madness, like living in limbo, living in fear,” Gutierrez Soto says, choking up at the memory. He recalls the filthy living quarters and foul food, the humiliating lack of privacy, the anguish of seeing his son in a prison uniform, the cruelty of the guards. At one point immigration officials threatened to send Oscar to a different camp, only relenting when a camp doctor warned that it could dangerously worsen Gutierrez Soto’s already high blood pressure.

“What they seek is to destroy you so that you go back to your country,” he says. “The guards are trained to do that, to make your life miserable.” But knowing he faced death if he returned to Mexico, he held out.

This past April, Gutierrez Soto was visited at the Texas detention facility by Lynette Clemetson, director of the U-M Wallace House. She’d gotten involved in his case in March, after the National Press Club invited Wallace House to join an amicus brief signed by some of the country’s top journalism organizations. She was there to interview him for a possible Knight-Wallace Fellowship, which brings mid-career journalists to Ann Arbor for a year of academic study.

He told Clemetson that he still wanted to return to journalism even after his long exile from the profession. She vetted the quality of his work and made sure that she could legally offer a fellowship to someone with an uncertain immigration status. Then, on May 3–World Press Freedom Day–she announced the fellowship at the National Press Club in Washington. “I announced that we were offering him the fellowship there, intentionally, publically, in a different way than we do for other people, hoping that the attention around the announcement might prompt some change,” she explains.

Gutierrez Soto and his son were released from detention a few months later. But Clemetson doesn’t think the involvement of Wallace House and its journalistic peers had anything to do with the government’s change of heart.

“I think they got out of detention for the most cynical of reasons,” she says, “because there were FOIAs in their case that showed that they were intentionally targeted [for deportation]. A judge had ordered that those emails be turned over–and right before the emails were supposed to be turned over, they were miraculously released.”

Clemetson expects that, like all Knight-Wallace fellows, Gutierrez Soto will develop his skills during his time here. But she also hopes “that the fellowship will help settle any dispute that the judge has that Emilio wasn’t really a journalist … that his life wasn’t really in danger. The validation of the fellowship and the university helps address those things.”

The fellowship isn’t the only support Gutierrez Soto has gotten from the Ann Arbor community. After a researcher at the University of New Mexico did an exhaustive search to compile more than 100 of his newspaper stories–which weren’t digitized or easily accessible–his legal team needed the documents translated on short order to submit to the court. “The Language Resource Center, here at the university, have this thing every year called a ‘translate-a-thon,'” Clemetson explains. “And they translated more than eighty of Emilio’s stories in one weekend, so that we could submit them to the court in early October by the deadline.”

Zingerman’s also got involved, training Oscar as a cook. “My son wants to become a chef,” Gutierrez Soto says. “He was learning about hospitality and services in Mexico. So now, he is going to learn at Zingerman’s. He is happy, very happy.”

Gutierrez Soto himself seems most struck by Ann Arbor’s diverse learning opportunities. “The spectrum of educational support that is offered here …” He laughs. “If someone wanted to get a doctorate in ‘enchiladas,’ they could get one. Enchiladas are from Mexico, but there are specialized people here who would find the formula to make the tastiest enchiladas in the world. Here everyone has an educational opportunity for whatever they want. It’s a nice city … and the people are very supportive, very attentive, very in tune with social justice issues.

“What is happening, the [anti-immigrant] phenomenon that is occurring, has not happened with all Americans,” he continues, choking up again. “And I have had the fortune to meet very good people, people with very big hearts. They have shown us a lot of solidarity, in a very humane way, and that is something that’s truly valuable.”

—

But it’s not yet clear if the efforts of Gutierrez Soto and his supporters will make any difference. At a hearing in October, it appeared that the judge had lost some of the evidence that had been submitted to the appeals court, including the translated newspaper articles and hundreds of pages from the Board of Immigration Appeals ruling. The judge went ahead with the hearing anyway, and said he would issue a ruling in January.

In the eyes of Gutierrez Soto’s allies, the mishap is one more sign that he was not getting a fair hearing. “They’re not interested in evidence,” says Clemetson, who testified at the October session, accompanied by another Knight-Wallace Fellow who went to support Gutierrez Soto and represent the fellowship class. “They’ve decided pretty much what the outcome will be.”

Even if the judge rules against him, Gutierrez Soto vows, he’ll appeal again, all the way to the Supreme Court if necessary. In the meantime, he’s moving ahead with his fellowship, attending events with students and colleagues, and considering his next steps–which may include writing a book.

“We have 140 journalists that have been murdered [in Mexico] since 2000,” he says. “That is something catastrophic for global journalism, not only for Mexico but for the world. But they don’t realize that even though they kill the messenger, the message arrives.”

—

This article has been edited since it was published in the December 2018 Ann Arbor Observer. The status of Gutierrez Soto’s court case has been corrected.