The University of Michigan is celebrating its bicentennial this year–just eighty years after it celebrated its centennial.

The odd arithmetic reflects some confusing early history: the university was stillborn in Detroit and only later transplanted to Ann Arbor. It took two state Supreme Court rulings (in 1856 and 1930) to certify 1817, rather than 1837, as its founding year. Which somehow didn’t stop the university from celebrating its centennial in 1937.

The university got the timeline straightened out in time to celebrate its sesquicentennial in 1967. This year’s bicentennial will mix celebration with soul-searching, including discussions about how to properly heed the fact that money from the sale of Native American land went into the funds that established the university.

—

Public education was a part of the original charter of the Northwest Territories, but it wasn’t till August 1817, that judge Augustus Woodward fleshed out a scheme for publicly funded academies, libraries, museums, and schools in the Michigan Territory. He called his creation the “Catholepistemiad” (a “system of universal science”); at its center was to be the University of Michigania, where such subjects as “anthropoglossica,” “physiognostica,” and “polemitica” would be taught. If none of those terms rings a bell, it’s because all were original coinages of the Greekophile Woodward.

Unlike most colleges out East, run by religious denominations, the system would be nonsectarian, and science and economics would be taught alongside the classical curriculum. And Woodward’s scheme followed the Prussian system of state-supervised primary, secondary, and university schools–not the British model of academies and universities for the children of the upper classes only.

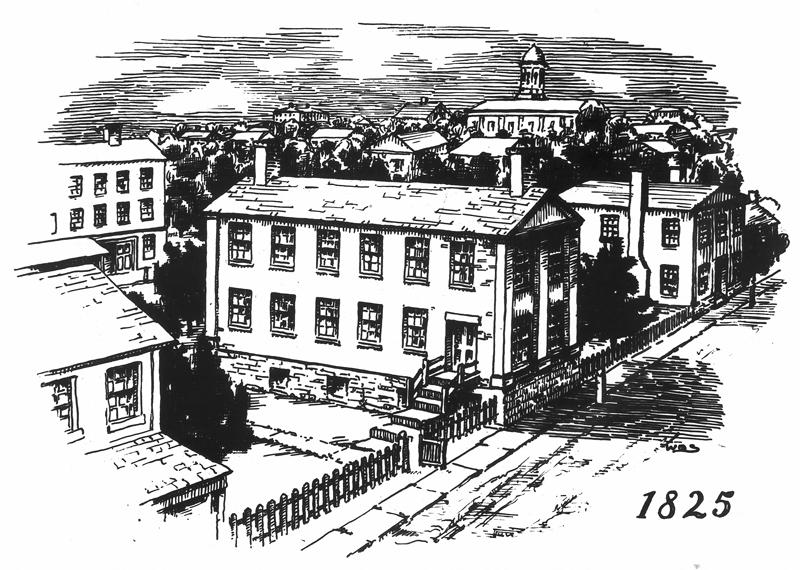

Thirteen professorships were designated, to be divided between a Catholic priest, Fr. Gabriel Richard, and a Protestant minister, the Rev. John Monteith. On September 24, 1817, a cornerstone was laid in Detroit, on the west side of Bates near Congress, and that fall a two-story building was erected there. The school and its employees’ salaries were underwritten by an award of $180 from the territorial government, but primarily by donations from Detroiters, including Woodward, and from Woodward’s Masonic lodge.

Five days after the laying of the cornerstone, territorial governor Lewis Cass signed the Treaty of Fort Meigs, in which the Native American tribes of the Ohio Valley gave up the rest of their land conquered in the French and Indian War and the War of 1812 to the U.S. government. A provision in the treaty specified that 640 acres near Monroe and other Native land in Detroit be given to the “new college in Detroit” and to St. Anne’s church across the street because some Indians were “attached to the Catholic religion” and might wish to have their children educated at the college. Sales of these lands benefited both the church and college, but there is no record of any Native children ever taking classes at the building on Bates.

Two hundred years ago, the concept of a government-sponsored college was still new. Because no students in the territory were sufficiently prepared to enter a university, Woodward’s vision was never fully realized.

Neither Richard nor Monteith ever taught at the Detroit building. Instead, its upper floor was an “academy,” roughly equivalent to a high school, for the study of Latin, Greek, and science. The first floor was a “Lancasterian school,” where older students helped teach younger ones.

When it opened on August 10, 1818, the building had just eleven students. By the following April, 130 students were paying tuition of $2.60 a quarter. Though enrollment at its peak approached 200, according to Farmer’s Detroit history, “most of the trustees and directors paid but little attention to the school.” Teachers came and went, and paper was so scarce that students learned to write by tracing letters in a box of sand.

By 1827, both the primary school and the academy had closed. After that, the building was available for rent by independent teachers hoping to get enough tuition-paying students to make a go of it.

—

In 1837, Michigan became a state. The new legislature approved a comprehensive public school system along the lines first envisioned by Woodward twenty years earlier. The assets and records of the Detroit school were turned over to a new board of regents, and Ann Arbor was selected as the new site for the university.

The financial Panic of 1837 hit the new state hard, and the Ann Arbor campus was slow to get off the ground. Meanwhile, the building on Bates was repaired, and in 1838 it reopened as a boys-only college with tuition of $5 a term. Fifty-nine students enrolled for the first term of 1839, dropping to twenty-five by the end of 1840.

The Ann Arbor campus held its first classes in 1841 with two professors and six students. That was the only year the U-M had official campuses in both Ann Arbor and Detroit–college classes on Bates ended after 1841.

The regents then leased the Detroit building to the city’s board of education. A high school opened there in 1844, but it too soon closed. In 1858, the building was demolished. In its thirty years, it had housed college classes for just three.

—

For more than a century, there were few traces of the university in its original hometown. But a dozen years ago, the U-M opened a “Detroit Center” on the corner of Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. and the street named after Judge Woodward. Though not an official campus, like those in Dearborn and Flint, it’s home to a variety of things Wolverine–an admissions office, a Hall of Fame for Detroit alumni, a School of Public Health project encouraging neighborhood “walking groups,” and the Michigan Engineering Zone, where Detroit high school students build and test robots.

An annual awards ceremony inducts new members into the Hall of Fame (the photos hanging on the wall include one of surgeon-turned-presidential candidate Ben Carson, now head of HUD). The Detroit Center also confers annual “Emerging Leader” awards for under-forty Detroiters and “outstanding service” awards for faculty and staff who’ve worked in the city.

The Detroit Center also serves as the home base for the U-M “Semester in Detroit,” where thirty students at a time live, study, and work in the city. U-M Dearborn runs an AmeriCorps “public allies” program there, and the center joins in community events such as Noel Night, when midtown Detroit cultural institutions open their doors for holiday caroling.

To mark the university’s bicentennial in September, Detroit Center acting director Feodies Shipp III says the center is hoping to unveil a documentary based on videotaped interviews with older Detroiters who are U-M grads conducted during its recent “Voices of Detroit” oral history project.

Of course, the U-M has always had informal ties to Detroit, with countless student and faculty research projects in a myriad of disciplines subjecting all manner of urban complexities to academic analysis. The Detroit Center’s efforts to flesh out a formal presence in the city for U-M are earnestly centered on putting the “public” back in “public university”–though in comparison to the grant-fueled behemoth in Ann Arbor, it’s not very well funded or highly prioritized.

Detroit is just an hour’s drive away from main campus, yet in many ways it’s a world apart. Grand ideas and scant resources–in a way, for U-M in Detroit, it’s 1817 all over again.