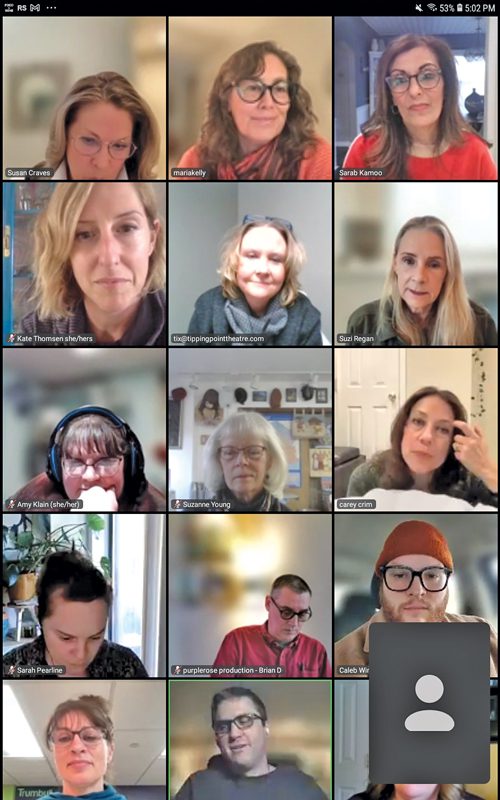

Playwright Carey Crim (middle row, right) says the virtual reading of What Springs Forth made it better—but it doesn’t always work that way. | Photo courtesy of Purple Rose Theatre Company

It was July of last year, and she had to finish What Springs Forth for a Zoom reading. It would be her first chance to hear her play—about “middle-aged friends who head for what they think will be a spa retreat and wind up battling [the elements], each other, and their inner demons”—read aloud.

She finished the draft, and the reading helped her pinpoint problems she had vaguely sensed: Two of the characters weren’t fully developed, “the second act wasn’t structurally sound, and it was too long,” she recalls. Crim fleshed out those characters, and made changes in act two that affected act one. “This allowed me to tighten the entire play.”

What Springs Forth opened at the Purple Rose on June 21 and runs through August 31.

Related: Purple Rose in Full Bloom: Jeff Daniels Reflects on his theater’s twenty-fifth anniversary

Play development has been a cornerstone of the Chelsea theater since the get-go. Artistic director emeritus Guy Sanville recalls that it began with private readings. “Then we forged a relationship with the Chelsea District Library, and we did public readings, probably eight times a year.” Readings were rehearsed once, on Friday, and presented Saturday mornings. Some were given a second reading, often at the Ann Arbor District Library.

The reading of What Springs Forth helped Crim make it better—but it doesn’t always work that way. In 2010, Sanville recalls, the playwright attended a rehearsal reading of one of her plays and decided it was hopeless. “We started the read-through,” Sanville says. “Carey said, ‘Can I talk to you? I f..king hate this. I don’t want to work on this anymore. I have another idea.’”

“The next day, Carey had act one of a new play, and that’s what they read,” recalls Rhiannon Ragland, the theater’s co-artistic associate. The unrehearsed reading impressed everyone, and the Rose produced Crim’s Some Couples May the next season.

Covid closed the theater in March 2020. Readings resumed in October of that year with Jeffry Chastang’s Under Ceege—not in the library but online. They’ve been virtual since.

Alvaro Saar Rios, who teaches playwriting at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, had a reading for his play Piggsville in May 2021. He says he was trying to create “a poetic language inspired by Shakespeare,” but “could only imagine what it sounded like in my head.” After the reading, he knew which lines sounded clunky. Audience questions in the chat box helped him see what was missing, and he added folk songs that tied scenes together.

Rios says Zoom conferences before the reading with Sanville helped everyone stay on the same page. “It was a great substitute for in-person conversations, and we were able to have more than one [even though] I was in Chicago.”

Rios also appreciated the chance to have a diverse company who read from different cities and to hear comments from people from across the country. “That play is set in a brewery and very influenced by the Wisconsin history of brewing,” says Rios, so feedback was particularly valuable from those who weren’t from the Midwest and had questions.

Ragland notes that in-person readings had to be done by local actors, usually those who were performing in or rehearsing a Purple Rose play at the time. Zoom allows the theater to cast from anywhere in the world.

Playwrights also appreciate the larger audiences. The room at the Chelsea District Library seats seventy-six—and those seats were usually all filled. Now many more people attend the Zoom readings.

One downside is the nature of the audience response. Resident playwright David MacGregor finds that although audiences are encouraged to register concerns in the chat box, many fall into their usual Internet habits: Either they’re “kind and supportive,” he says, or just snarky. And unlike in-person readings, “people don’t typically respond to what other people are saying in terms of agreeing or disagreeing or expanding on a point someone else has made. An in-person reading is a shared, collective experience for the performers and the audience.”

To get that, “you have to read plays out loud in front of an audience,” says Sanville, who was at the helm when the theater transitioned from in-person to Zoom. Online, “you read something that was so beautiful, and it just lay there.”

“I find it so difficult to get a sense of rhythm or anything else without the audience there and the actors in the same room,” Crim reflects.

Lucas Daniels, the theater’s other co-artistic associate, notes that technical issues can arise, too. Because readers are in different locations, “it’s hard to do overlapping dialogue with time delays.”

Daniels says bringing casts together from all over the country can be a scheduling nightmare, but it’s also a plus. Not only can the readings be cast with ideal actors for the roles, it gives the Rose a chance to audition actors who don’t live nearby. A New York–based actor who participated in a recent reading will appear in an upcoming production.

“I think the ideal situation for me would be actors in the same room with a camera so that anyone anywhere can watch the reading, but the actors would be together and maybe even have a small audience just to get that live audience feedback and feel,” says Crim.

Does she feel it was worth the pressure to finish a draft for that Zoom reading? Absolutely. “One thing that’s great about reading,” Crim says, “is the deadline.”

Next up is Surrogate by playwright/actor Lauren Knox Mounsey on July 13. To participate, sign up at bit.ly/SurrogateReading.