Senior Claudia Virgen says she “definitely dealt with the impostor syndrome—doubting my skills and successes, wondering if I deserved to be here.” | Photo by J. Adrian Wylie

This year, the U-M saw a 24.5 percent increase in applications from first-generation students; they currently make up 12 percent of the undergraduate population. But the university’s relationship with first-gens hasn’t always been supportive.

On a bitterly cold but sunny day in January 2009, five students visited the registrar’s office. They wanted to know how many first-gen undergrads were enrolled at the U-M so they could invite them to their new club: First Generation College Students @ Michigan (FGCS@M). “The university doesn’t release this information,” they were told by a well-intentioned staffer, ‘because being first-gen is a ‘negative stigma’ at the University of Michigan.”

Stunned, they left.

FGCS@M had been founded the previous year as a place for students to share experiences as the first in their immediate families to attend college. Our motto was: “We may be the first, but we won’t be the last.” Dwight was their faculty advisor. A first-generation student himself when he enrolled at St. Patrick’s College in California in 1968, he was deeply invested in nurturing these students, meeting their needs, and helping them attain their goals. Not only was FGCS@M the first such group on campus, it was the first at any U.S. college.

Their experience at the registrar’s office left the students deeply hurt.

“Does Michigan want us to be here?” they asked at our next meeting. “Are first-gens supposed to be quiet and invisible?”

We were disappointed but not surprised. We tried to be strong for them, and Dwight assured them that the sociology department was proud of them and would support their efforts to be visible and thrive.

First-generation students have always been present on college campuses, but the term “first-generation students” is relatively new. It was coined in the late 1970s, when Congress reauthorized the Higher Education Act, to help clarify admission criteria for academic assistance programs.

In the U-M’s early days, most of its students were the sons of Michigan farmers. “In 1886, the university polled 1,406 students about the professions of their parents,” emails Kim Clarke, senior writer for the Bentley Historical Library. “502 were farmers, 171 retail and wholesale merchants, 93 lawyers, 83 physicians, 54 mechanics, 52 manufacturers, 51 clergymen, 41 lumbermen and builders, 33 real estate and insurance agents, 28 bankers, and 26 teachers.”

A college education would remain a rare accomplishment in the U.S. until the mid-twentieth century. In 1940, more than half the population left school after eighth grade, and just 6 percent of men and 4 percent of women had a college degree.

But after WWII the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act—the “GI Bill”—opened the door to higher education for veterans from all social classes. College enrollment increased by half in the 1950s and more than doubled in the 1960s. Government programs created new opportunities for economically disadvantaged students: work-study jobs in the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, and guaranteed student loans in the Higher Education Act of 1965.

But in our personal experience, first-gens were still invisible. If we found one another on campus, it was without institutional encouragement or support. Being first-gen was simply unrecognized by campus administrators.

In the decades that followed, more student loans and grants, affirmative action, and the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 opened more doors to traditionally underrepresented students. But although expanded institutional initiatives helped bring more first-gen students to campus, once they arrived they found themselves in uncharted terrain.

“The first-gen identity can be an invisible, even lonely identity,” says Rosario Ceballo. Herself a first-generation student, she’s now dean of LSA. | Erin Kirkland, Michigan Photography

LSA dean Rosario Ceballo exudes confidence. But like so many first-generation students, she says she’s struggled with impostor syndrome—feelings of self-doubt and inadequacy, and the sense that you’ve somehow tricked everyone into thinking you belong.

“Since so much of the academic world and social life in college was new to me and my family, I’ve come to accept that a small part of me always wonders about my place in academia,” Ceballo admits. “Your logical mind can tell you all the reasons why you belong here as much as anyone else, but doubt can easily sneak up on you when something doesn’t go well.”

Although there have been strides in making first-gens feel welcome since Ceballo was a student, feelings of doubt are still common.

“When I started Michigan, I didn’t feel like I belonged,” says senior and FGCS@M president Claudia Virgen. “I definitely dealt with the impostor syndrome—doubting my skills and successes, wondering if I deserved to be here.”

Other first-gens say they feel like they’re living on an island surrounded by peers with very different backgrounds: at the U-M, two-thirds of students come from families making more than $110,000 per year.

“I’ve always felt proud to be the trailblazer in my family, and I feel that I was able to ‘open the eyes’ of those with whom I connected with a little bit by giving them introspection to a situation different from their own,” says alum Pablo Garcia Moreno, a former FGCS@M vice president. Still, “I didn’t have a safety net, as many of my more affluent peers seemed to have.

“My father had very good advice about crossing class boundaries,” he adds. “I shouldn’t leave any opportunity or money on the table. Take advantage of any available income, grants, and loans. Don’t stand back and be afraid to compete.”

It is good advice, but it also reflects a disparity between first-gen students and their continuing-generation counterparts: parents with a college degree can share the lessons they learned at school, but parents of first-gens are sending their children into a wholly unfamiliar environment.

“Even though my parents always encouraged me to go to college, they didn’t know how to help me after I got here,” says current FGCS@M vice president Abdullah Ahsan.

And while upward mobility is rightly celebrated, many first-gens are concerned about how college will impact their relationship with their families and the communities where they grew up. Some, like Virgen, fear that they’ll “disappoint community and family.” Others, like alum and former FGCS@M president Anabelle Dally, put pressure on themselves.

“When I started at Michigan, I only saw one option—to succeed,” Dally says. “I tried to not think about the risk of failure.”

Others feel a sense of distance. First-gen and LSA administrator Norris Chase says the upward mobility “polishing process” can leave students “feeling more disconnected from their home communities and their sense of identity, while working to survive and thrive in a unique and competitive academic environment.”

This can put first-gens in what’s known in sociology as a liminal state—suspended between two worlds, neither one nor the other. How does one remain connected with one’s past as the present is encountered and the future is envisioned? First-gen inner identity and family history often clash with a slowly emerging middle-class self—as if college weren’t hard enough on its own!

Some students, like Nahomi Gonzalez, who is earning a master’s in social work, push back against the implication that education is “a progression, a transition to something ‘better’ or more ‘refined.’”

Higher education “values assimilation, inherently push[ing] you away from your upbringing environments,” she says. “For me, and for many other first-gens, upward mobility or becoming more ‘successful’ within a system that will never accept us isn’t a goal. It’s about rejecting that system, questioning the very notion of hierarchy, and resisting the idea that we need to ‘pass through’ some predefined threshold to prove our worth.”

Alum Yadah Ramirez says she’s adapted by “code-switching”—presenting “one representation of self in more affluent, educated, White spaces, and another representation of self in non-affluent, less educated, non-White spaces.”

But “when this becomes a daily practice, you start to question who you are,” Ramirez observes. “With all the switching, you end up changing a little.”

“I don’t see code-switching as a negative,” says Moreno. “Rather, I am comfortable and empowered using it. As I find myself crossing class boundaries, I use code-switching as a method, not to alienate either side, but rather to build bridges.”

In addition to the struggle to maintain or define identity, the stress of not being able to draw on their parents’ experience, and the pressure of expectations both external and internal, first-gens may also feel the sting of being misunderstood.

“As a graduate student in the School of Social Work, where most are passionate about helping the impoverished, I often find myself met with puzzled looks when discussing my experiences—particularly around the impact of social class,” Gonzalez says.

But it would be an incomplete picture of the first-gen experience to simply list its challenges. For some, it’s simply not a big deal—even when financial constraints made it harder to pursue certain opportunities. “As someone with limited financial security,” Moreno says, he had to work during the summers. “Nonetheless, when others told me they were getting internships, I would congratulate them. … They were always empathetic to my situation and it was never a big deal, rather just another part of my path.”

And, true to his father’s advice, he got a scholarship and grant money to study abroad.

“Boundary crossing and learning to navigate different spaces simultaneously [are] the largest strengths first-generation students bring with them to campus,” says Terra Molengraff. A first-gen student as a U-M undergrad, she went on to get a master’s at Michigan and a PhD at the University of Minnesota.

The enrichment of higher education and the opportunities it yields are powerful rewards.

“I’m succeeding, and my parents and grandmother are proud of me,” says Virgen. “I’m helping my family and repaying what they’ve given me.”

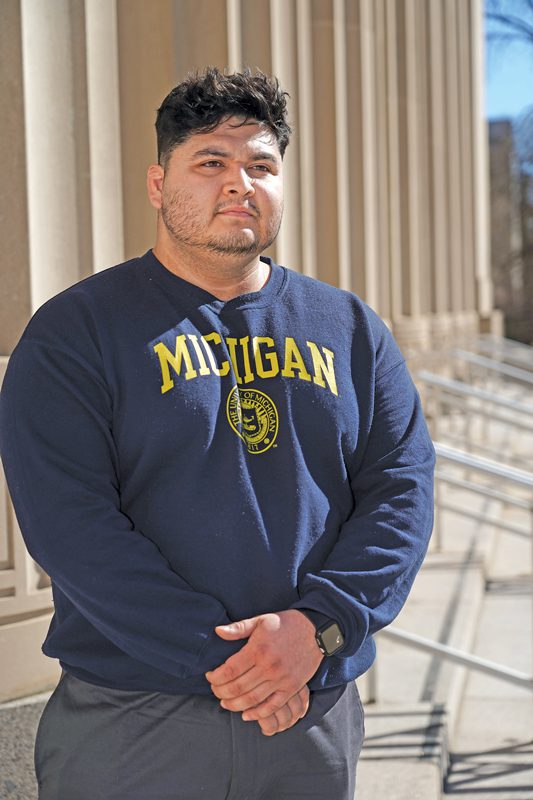

Pablo Garcia Moreno worked summers while other students did internships. “I didn’t have a safety net, as so many of my more affluent peers seemed to have.” | Photo by J. Adrian Wylie

Year after year, FGCS@M worked to recognize, raise awareness of, and resolve challenges faced by first-gen students. With these core values in mind, students set up information tables at FestiFall and Winterfest and organized first-gen dinners in the Michigan League Ballroom and Union Rogel Ballroom. The small first-gen graduations that we held in our home on Wells St. grew into annual events with hundreds of students and their families.

There were other institutional strides in supporting first-gen students. In 2017, the university established the First Generation Student Gateway, where Molengraff now leads first-generation initiatives. It supports students as they negotiate academic and social campus life, raises awareness of first-gen experiences, and empowers first-gens to be confidently visible. The LSA First-Generation Commitment, where Chase serves as director, provides additional supports for first-gens. The Kessler Scholars Program awards $15,000 to $25,000 per year for first-gen students. And the Go Blue Guarantee, introduced in 2018, has made it easier for Michigan first-gens to attend by giving qualifying students from families earning less than $125,000 free or reduced tuition.

Today, of the U-M’s 34,454 undergrads, more than 4,000 are first-gen. And first-gens aren’t found only in the classrooms—they’re also in the administration.

“I think it’s so important that we, as first-gen faculty and administrators, share our experiences with students,” says Ceballo. “The first-gen identity can be an invisible, even lonely identity, but when we publicly proclaim our first-gen identity we help each other recognize the pride, courage, and resilience in being first-gen.”

Still, some feel the university could do more to increase visibility.

“I’m still not always proud to say I’m first-gen,” says Ahsan. “The university needs to use social media to make first-gens more visible. … There should be more focus on first-gen experiences and struggles. This would help first-gens deal with their hesitancy to talk about their

social-class backgrounds.”

“First-generation students make the university better, because they bring insights from their home communities and use their experiences at Michigan to make the world a better place,” says Molengraff. “For many, it’s never only about them. It’s about them and their community.”

And just like other college students, their classmates are an essential part of that community.

“As students we all find ourselves in the same stage of life … despite the different paths we take to arrive to this stage and the different strategies we use to meet the same goal,” observes Moreno. “For me, after starting Michigan, all social-class differences seemed to melt away. We students were all in this together.”

Dwight Lang is first-gen, a sociologist, and a retired lecturer in the Sociology Department at U-M Ann Arbor.

Sylvia Wanner Lang is first-gen, a sociologist, and a retired researcher in several colleges at U-M Ann Arbor.

Thank you for this enlightening article on first-generation college students. As a first-gen student in 1975, I remember feeling incredibly insecure. Now, I understand—like Dean Rosario Ceballo—that I was experiencing imposter syndrome. Reading about how different first-gen students have adapted over time is both insightful and revealing of broader cultural dynamics.

I particularly appreciated Nahomi Gonzalez’s powerful reflection: “For me, and for many other first-gens, upward mobility or becoming more ‘successful’ within a system that will never accept us isn’t a goal. It’s about rejecting that system, questioning the very notion of hierarchy, and resisting the idea that we need to ‘pass through’ some predefined threshold to prove our worth.” Her perspective, along with Mr. Moreno’s mention of students facing “limited financial security,” raises an important question:

How can a student with limited financial means embrace the outlook of “rejecting the system,” when, in reality, they must function within it—especially given the ever-increasing cost of higher education?

Mary, your insight and personal experience being a first gen are well taken! You tell an important story that happened 50 years ago for you and is persistent: often still alive and well for current first gens in 2025. Indeed, overcoming financial strain coupled with strong feelings of questioning their right to a college education are conditions that make first gens the amazing boundary-crossers and risk-takers they become on the path to success. And you are one of them! The UM has Go Blue Guarantee, and more programs that now help with the cost, and a forum for finding fellow first-gens is just as important emotionally. The Gateway, first gen groups in schools/colleges across campus, and a growing number of administrators at UM are helping to raise awareness about first gens as vital to campus diversity.

Thanks for your insightful comments Mary. Yes the imposter syndrome is always present for first-gens – even now in 2025. And this will likely persist as first-gen continue enrolling in college beyond the high school years. Hopefully colleges like Michigan will recognize this challenge and establish effective program to enable first gens to thrive and succeed. Nahomi’s comments are accurate as she questions the effectiveness of college systems that have not always been structured to recognize and support first-gens. But things are changing now at Michigan. Even the problem of limited financial security is now being addressed here in Ann Arbor.

I absolutely love this work and the way this article captures the historic and contemporary elements of first-generation work at the university. The students, faculty, and staff are collaborators in creating more accessible environments for students to thrive and this article captured this perfectly. Thank you Sylvia and Dwight for your tireless work and investments in this crucially impactful sector of the University of Michigan. The legacy of the foundational work is key, and we, in LSA are “standing on the shoulders of giants” as the old adage goes.

Norris, we are honored to have been able to present first generation awareness, work, and evolution happening at the University to the broader Ann Arbor community as well to the UM in this Ann Arbor Observer publication. We are grateful to have been able to work with the Observer editors to make this much needed story happen.

Christopher, a sincere “thank you” for sharing your insightful understanding of what the work world can hold for first gens nearly a decade after graduation! We solute you! Indeed, first gen superpowers including code-switching to communicate across social class boundaries are, and always have been, incredible abilities first gens know and use throughout many relationship arenas in life. It is most impowering to know, well into retirement years, that as first gens we can and do skillfully cross social “walks of life” to get the job of building communication bridges done and completed well.

Norris, You’re so correct to say that support for Michigan’s first-gens is a campus-wide, collaborative effort of students, faculty, and staff. When first-gens know this they’re much more likely to thrive on a campus where they’re in a distinct minority. This is critical. When first-gens know that support systems exist. when they know that people understand they’re present they’re more likely to succeed and realize their potential. Thanks for all you do for Michigan’s first-gens. Go Blue!

This piece, another great one by Dwight, Sylvia, and the FGCS@M community feels more timely than ever. As a First Gen student myself (B.S.E. ’16, M.S.E. ’17), I vividly recall the challenges described herein. In my time, we wrote articles that focused on the challenges, and perhaps then ended with a nice “triumphant” message of graduation.

This article, however, gets to the deeper meaning behind being a First-Gen that it’s taken me even many years to begin to understand. We never talked about these key “superpowers” the first-gens, by overcoming obstacles, obtain! I resonant very much with Alum Yadah Ramirez and the comments on “code-switching”. I’ve been hailed in my career, as an engineer, who can build lasting relationships with people from all walks of life. I often chalked it up to just my interpersonal skills, but in reality it’s built from years of “code-switching” between my upbringing (blue-collar) and my higher-education path.

Thank you so much, Dwight and Sylvia, for giving students a voice and always looking at what’s next in this ongoing story. I note this is especially timely because of the need for leadership in our world to be able to communicate effectively across all social boundaries. Too often, upper-middle/upper class persons talk in a very different language that, even if the message is good for underrepresented persons, may be just misunderstood or even worse give the opposite impression of the movement, legislation, or initiative. Perhaps we could all learn a thing or two about the superpowers that first-gens gain, by overcoming great adversity, to be able to communicate across all levels of society, understand impacts of policy to a variety of classes, and building community.

Or…to put it in my “code-switched” language – Higher-education could learn a thing or two about speaking in plain and simple terms that is easy to understand and doesn’t waste peoples time trying to translate the message! Speak in a language ALL people can understand!

Christopher, a sincere “thank you” for sharing your insightful understanding of what the work world can hold for first gens nearly a decade after graduation! We solute you! Indeed, first gen superpowers including code-switching to communicate across social class boundaries are, and always have been, incredible abilities first gens know and use throughout many relationship arenas in life. It is most impowering to know, well into retirement years, that as first gens we can and do skillfully cross social “walks of life” to get the job of building communication bridges done and completed well.

Chris, Thanks for your insightful comments about challenges of being first-gen at Michigan. Yes student/staff comments in this essay get to important core aspects – often hidden – of subtle first-gen experiences. Indeed, “code-switching” is always present for first-gens as they adjust to campus life Being on campus is much more than academics for first-gens – it is often about adjusting to a world very different from where they were raised and grew up. Being on campus is usually/also about being upwardly mobile, something middle and upper and middle class students aren’t dealing with. And yes “code-switching” is pat of this and extends beyond the four short years on campus. It’s a life-time undertaking as first-gens willing move into very different social worlds. And yes using words that everyone can understand is an important suggestion that would help facilitate better communication across constructed social class boundaries and divisions. This is why first gens – once they graduate and move into the work world and life, can be effective in interacting with people and facilitating communication. Thanks again and Go Blue!