On January 6, Molly Rowan-Deckart moved in to guide the theater into its next century. A couple of topics have already “risen to the top” of her to-do list, she says. One is making the theater more accessible both physically, with an elevator, and economically, with scholarships to their summer film camp. | Photo by J. Adrian Wylie

The best thing about Liberty St., one could argue, is the Michigan Theater. Along with hundreds of films every year, it hosts concerts, children’s theater, celebrity artists, and dozens of other major events. Its recreated historic sign is a landmark rivaled only by its sister theater a block away, the State. That streetscape—with the U-M’s Burton Tower rising in the background—inspired the Michigan Theater Foundation’s recent rebranding as Marquee Arts.

The theater’s history is dominated by just two people: Jerry Hoag ran it for Butterfield Theaters from its opening in 1928 until his retirement in 1974. In 1982, after a public-private effort rescued it from redevelopment, it was placed in the hands of Russ Collins, then twenty-six. He led its restoration and growth until January 5, 2025, retiring exactly three years shy of the theater’s hundredth anniversary.

Collins and his wife Deb Polich—who’d also just retired, as CEO of Creative Washtenaw—left immediately on a round-the-world cruise. On January 6, Molly Rowan-Deckart moved in to guide the theater into its next century.

There are challenges: the building has expensive needs, and its audience never fully returned after the pandemic. But Rowan-Deckart, who most recently ran the Alliance for the Arts in Fort Myers, Florida, is upbeat.

Marquee Arts is “a storied organization with [a] long history of evolution and restoration,” she says. “The first six months of any new role I just try to be available and to listen to the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

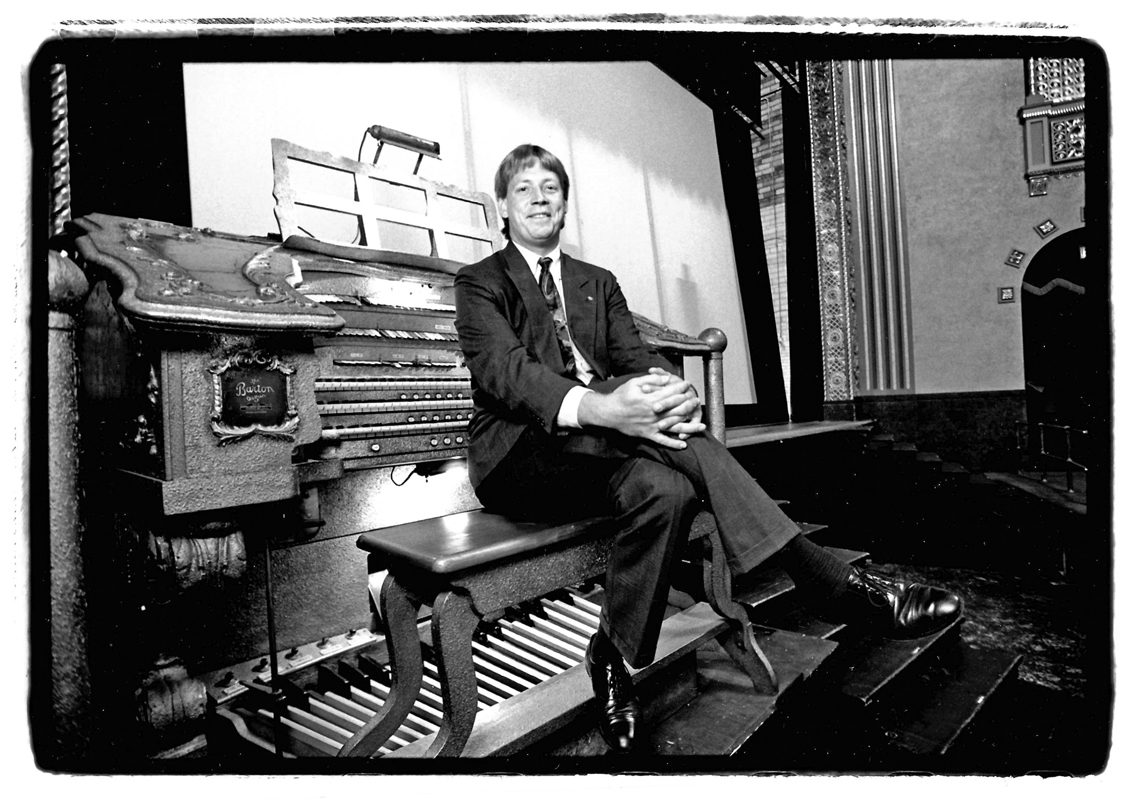

Almost every town, Collins says, once had a historic theater, but not every town saved theirs. The Michigan was saved by its Barton Organ.

Designed to provide a dramatic accompaniment to silent films, it’s “all organ pipes or actual xylophones … and snare drums that are being struck,” Collins says. “What you’re hearing in a sense is a one-man band.”

Though talkies arrived less than two years after the Michigan opened, Hoag always kept the organ in working order. “He is critically important to how the Michigan Theater developed,” Collins writes in a history of the theater, “and his love and support of the Barton Organ was a key reason why the theater was saved.”

By the 1970s, “movies had lost their popular culture and entertainment business dominance to television,” he writes, and the Michigan competed for a dwindling audience with the newer Fifth Forum nearby, theaters in Briarwood and the Maple Village shopping center, and “a plethora of University of Michigan student film societies.”

When Butterfield’s lease expired in 1978, he writes, the Michigan was on the brink of being converted to a food court when “Dr. Henry Aldridge and a volunteer group of people who worked to restore and play the Barton Theatre Organ rallied the community to save the theater.”

Aldridge appealed to then-mayor Lou Belcher, who in a 1999 Observer article recalled personally signing a purchase agreement for the building. Learning that Butterfield wanted another $100,000 for the seats and organ, he next persuaded philanthropist Margaret Towsley to donate the money—and only then rounded up the eight votes he needed to make it an official city purchase. A nonprofit was set up to operate and restore the theater, and two years later, Collins was hired.

He’d already put on musicals there through his own production company, and one of his first moves as executive director was to bring in a touring Broadway show, Amadeus. “Oh my goodness, that show just looked spectacular in the Michigan Theater,” he says. “We sold out two shows.”

Along with a diverse range of films, he continued to bring in live performances, from the Philip Glass Ensemble to the juggling-and-comedy troupe the Flying Karamazov Brothers. “Just beautiful stuff,” he says. “These are the things the Musical Society does now. We did it first.”

One capital campaign raised money to restore the main floor and foyer; they held another for the balcony, outer lobby, and facade. In 1999, the Michigan staff started programming the State Theatre as well. In the mid-2010s, when the State’s four screens were threatened with closure, it bought and restored that theater, too. Both theaters now host the annual Cinetopia Film Festival.

Cinetopia, like everything else, hit a hard stop during Covid-19. Fortunately, “the community was really supportive,” Collins says. “And then various government programs were very helpful.

“There was this confidence that somehow we would make it through. How, we had no idea. … You’re putting on your ‘difficult time’ hat. That’s what you do.”

Russ Collins in 1994 with the Michigan’s Barton Organ. Though talkies came in less than two years after the theater opened, his predecessor Jerry Hoag always kept it in working order—and organ aficionados were the first to rally to save the theater. | Photo by Peter Yates

Collins is sixty-eight, but he’d planned to stay on till the hundredth anniversary in 2028. The pandemic—and the Barbie movie—made him reconsider.

He thinks of the excitement surrounding the movie as “kind of the big breath that people took as the Covid pandemic was ebbing away.” He saw “a lot of people in the theater,” and the organ—newly rebuilt—was playing again.

But he also saw how much the world had changed. “Essentially, between 2020 and 2022, the demographic shifts in the audience were the demographic shifts expected to happen between 2020 and 2030,” he says. Many Baby Boomers “graduated—stopped coming to the theater—after 2020.” When they did return, it was in smaller numbers—a drop-off demographers hadn’t expected to see till the end of the decade.

“Same thing with technology,” Collins says. Things like remote work, video conferencing, and AI “all got sped up. … [If] you look back at the changes in the adoption of certain technology, the adoption of certain kinds of social practices, the same kind of thing happened during the Depression and during WWII. So those very, very big social dislocations in society tend to speed up how the society works, and that speeding up is really dislocating.

“That’s basically my big takeaway from the pandemic. And it made it clear to me that it really was time for the next generation to take over.” At forty-five, Rowan-Deckart hits the demographic mark.

Collins and Polich met working at the Michigan and married in 1994. It’s a second marriage for both, and between them they have three children and eight grandchildren. All live in Washtenaw County, and they have no plans to move in retirement.

But neither, Collins says, did they want to be “either implicitly or actually hovering” over their successors. And “for ourselves, because we have been so committed to our communities and careers, we thought it might be good for us to get out of town so we can think about what that next chapter’s going to be.” So right after Collins retired, they left on their four-month-long cruise.

Longtime local banker and Marquee Arts board treasurer Peter Schork describes how they chose their next leader.

“We hard-interviewed, for a long period of time, seven candidates out of almost 150 who applied,” he says. “We have six movie theaters plus a very fine live entertainment facility, so we hired someone who was really good at both.”

Schork thinks Rowan-Deckart is “going to be great. She’s focused. And I think she’s gonna do some nice things in terms of taking us into the next decades.”

She’ll get some help from Collins. “Molly has four months of putting her stamp on things,” Schork says, “and then Russ is going to return. He’ll be an employee, “preparing for the hundredth birthday and a capital campaign.”

The Michigan “has some pretty major costs coming up in the next five years,” Schork explains. “The roof. Very major. Also the back stage. For years we tried to make that more accessible and more modernized. There’s some additional work around the building. … Russ has a master plan to get some more funds in to finish it off.”

Starting in October, Rowan-Deckart spent one week a month in Ann Arbor, shadowing Collins. They “just hung out,” she says. “We crawled all over the theater, under the stage, in the fan room—you can tell how much he loves this organization, how lovingly he’s restored it. It’s beautiful.”

She grew up in New Jersey, “and then moved west”—her family moved to Boise, Idaho. She graduated from Boise State University with a fine arts degree, but “watched so many of my creative friends leave [that] I became really invested in the concept of building infrastructure to keep creative people anchored to their state.” While working in film, she “served on a lot of civic boards [and] led initiatives to pass tax rebate legislation in Western states regarding film production.”

Then film production also shut down during the pandemic. “I was like, ‘Whew, I have [three] kids to feed. I have to work this out.’ I got a job offer in Memphis and a great job offer in Fort Myers, and the kids and I chose Fort Myers.”

According to her LinkedIn bio, she created the Alliance for the Arts’ first endowed scholarship, built a digital arts lab, and “[r]etrofitted the traditional performing arts space to include a cinema, making this the only independent movie house within 90 miles.” But her life circumstances changed—she went through a divorce—and after four years, she was ready to move again. A friend spotted the Michigan opening, and Rowan-Deckart applied.

In February she still hadn’t figured out what to do with her office. “It’s this weird little dogleg. It doesn’t have windows. It has, like, a couple doors.” But she’s been “bebopping around” and meeting “a lot of the other nonprofit arts leaders. … I went to Chelsea last weekend and saw Jeff Daniels’s performance. I went to Detroit a few times. … The DIA, my gosh.”

For now it’s just her and her youngest, Rowan; she says he’s adjusting well at Clague Middle School. They’re in a rented condo on the north side while she looks for a house. Her oldest, Maisie, is taking a gap year and traveling, while high-schooler Mia is “finishing out her school year [in Florida] because she has a great Europe trip coming up this spring.”

A couple of topics have already “risen to the top” of her to-do list, Rowan-Deckart says. One is making the theater more accessible both physically, with an elevator, and economically, with scholarships to their summer film camp. “I think arts are for everyone,” she says, “regardless of your ability to pay.”

The other is the Marquee Arts website and especially how hard it is to buy tickets online. “The agency that was tapped to do the rebrand partnered with a company in Sweden, and the whole website was hard-coded in Swedish,” she says. “You can imagine the problems that that’s causing. It’s like being held hostage by your own brand.

“It is this weird unravelling we have to do, but I am very committed to it, because it is an issue. And I think it’s okay to say, ‘Yeah, you’re right, we screwed up. We’re going to fix it.’”

She agrees with Collins “that the pandemic expedited trends that were already underway, particularly with the rise of streaming platforms and other at-home entertainment options.” But she sees opportunities in “experiential film events—such as interactive screenings, filmmaker Q&As, and themed festivals”—and a “significant potential to increase live event programming, especially featuring touring musicians. With one of the best venues in Ann Arbor, we have a distinct advantage in creating intimate, memorable live music experiences that draw audiences back to our space and foster community connections.

“Additionally, I believe we should focus on cultivating the next generation of cinephiles and arts patrons. Building robust educational initiatives, partnering with schools, and increasing our community presence can help ensure younger audiences see our venue as an essential cultural hub. … We need to look at how we attract new audiences.”

She says she’ll be on a listening tour for the next six months. “I always like to hang my shingle. My door is always open. I don’t know what I don’t know yet.”

She’s realistic about her musical ambitions. “Post-Covid, bands have gotten markedly more expensive in their asks. When I say that, I mean from five figures to heavy six figures. And we have seating constraints, so some of those shows won’t ever pencil out with 1,600 seats.”

But big arenas have their own drawbacks. “I think there’s an appetite both for artists and concertgoers to have a more intimate setting,” she says.

“The Michigan is well positioned to lure some acts. And who doesn’t want to come to Ann Arbor?”

Calls & Letters, May 2025: The Michigan’s managers

To the Observer:

I thought there would be others who caught this, but I didn’t see anything about it in the new Observer, so I guess not. The piece about Molly Rowan-Deckart in the March issue said she was only the third manager in the Michigan Theater’s history, after Jerry Hoag and Russ Collins.

Nope. A guy named Ray Messler was its first manager after it was bought by the city in 1980. He resigned in July 1982 after a bizarre disappearance, which I covered as a general assignment reporter for the Ann Arbor News.

Thanks to the newpaper’s impressive array of out-of-town phone directories, I tracked him down at his sister’s house in St. Louis. He professed bewilderment that there had been any fuss. Which I found bewildering.

Thought you might like to know. 🙂

Sincerely,

Jeff Mortimer