In late December 1848, Ann Arbor’s Michigan Argus carried an advertisement for a “Goldometer.” Y-shaped like a dowsing rod, it would be “sent by mail, closely enveloped and sealed, and therefore, not subject to inspection by postmasters, for the sum of THREE DOLLARS.” That was a lot of money then–equal to nearly $100 today–but the price included a book called the Gold Seekers Guide.

And with that, Ann Arbor joined the California gold rush. The first discovery at Sutter’s Mill had come that January, but it had taken till summer for word to reach the East Coast. It was officially confirmed by president James Polk in a December address to Congress. And now, the frenzy was on.

On January 10, 1849, the Argus explained how to get from New York to San Francisco by sea. The article ended: “So here’s a chance for all who wish to try their fortunes in the gold regions.”

Forty-three-year-old George Corselius, a newspaper publisher and bookseller, was among the first to depart. According to the April 11 issue of the Washtenaw Whig, Corselius traveled first to New Orleans, where he embarked for the Isthmus of Panama.

According to Russell Bidlack’s 1960 book Letters Home: Ann Arbor’s Forty-Niners, Corselius had suffered financial reverses, and imagined that a warmer climate might cure his tuberculosis. He promised the editor of the True Democrat that he would send accounts of his trip.

But Corselius never reached California. In an April 11 letter, he wrote that he had made it to Panama, but after trekking overland across the isthmus, found so many gold seekers ahead of him that ships for San Francisco were booked weeks in advance.

Ill and exhausted, with most of his funds depleted, he plodded his way back to the Atlantic coast. He died aboard the steamer Crescent City before it reached New York, and was buried at sea. He left behind a widow and four children in Ann Arbor.

—

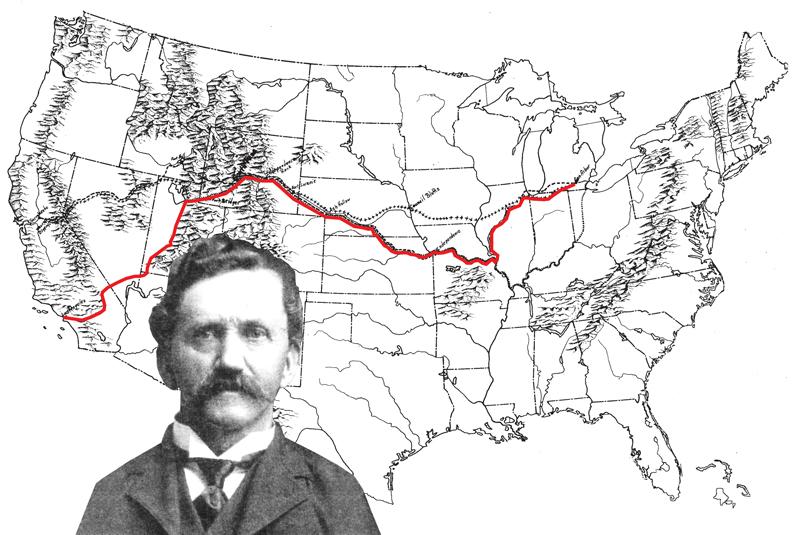

In a 1960 “Ann Arbor Yesterdays” column in the Ann Arbor News, local historian Lela Duff described the three main routes to California: through Panama’s malarial jungle; the long sea voyage around Cape Horn; and overland.

In the January 24, 1849 Washtenaw Whig, Samuel Gould advertised himself as “an experienced guide” for the overland route. According to Bidlack, he’d recently joined the Mormon Church in Salt Lake City, which had sent him back to Michigan for missionary work.

Stonemason Robert Davidson set out overland with brothers DeWitt and James Downer, two young farmers. Davidson sold his Ann Arbor home for $1,200, and DeWitt sold his property for $1,300.

David McCollum also teamed up with two younger men: Charles Cranson, the son of a farmer, and C.M. Sinclair, a store clerk. McCollum and a former business partner sold two properties for $5,000, and McCollum used his share to finance the trip.

The “jumping-off point” for the overland route was Independence, Missouri. But spring came late in 1849, and cholera stalked the camps where the forty-niners waited to depart.

When McCollum came down with a “bilious fever,” his group decided to throw their lot in with the Pioneer Line wagon train. The Washtenaw Whig reported that each paid $200 to join the year’s first train. It was not a bad price, considering that the going price of a mule in Independence at the time was at least $100.

Caleb Ormsby also went overland. A physician, he’d platted the first addition to John Allen and Elisha Rumsey’s square-mile city, but like Allen, he suffered in the Panic of 1837 and hoped to repair his fortunes in the gold fields.

In September, the Washtenaw Whig published a letter from Ornsby describing a “swarm of emigrants of men women and children of all characters and colors with their thousands of mules, horses, oxen and cows, waggons carts and spring carriages … now putting forward for the great Eldorado of the West.”

The letter, written on June 30, opened in an optimistic tenor; his small party of four were all in good health, and had eight good animals–four to ride and four to pack. Even so, like many others, they had been forced to discard items they couldn’t carry: he described wagons, kegs of powder, guns and ammunition, farming and mining tools, clothing, and cooking utensils all abandoned along the trail. And sickness and accidents were taking their toll. He encountered one man who was dying after a wagon ran over his head, and others shot in quarrels and accidents.

A letter from McCollum, also printed in September, painted an even darker picture: both Sinclair and Cranson had died on the trail. In a single day McCollum had counted eighteen freshly dug graves.

—

Davidson’s expedition was the first to reach California, arriving at “Weaver’s Diggins,” fifty miles from Sacramento, on August 15. By August 18, Davidson had dug $150 in gold. A letter from D.C. Downer, dated September 23, 1849, and published in the March 30, 1850 Argus, tells of more modest finds on the American River.

Next to arrive was another former Ann Arbor physician, Thomas Blackwood. He landed in San Francisco on September 15, after a cold, sodden, six-month voyage aboard the Loo Choo around Cape Horn. McCollum reached Sacramento a month later, on October 14, after his arduous five-month journey from Independence.

In a letter printed in the December 19, 1849, Argus, McCollum described bouts of sickness with bilious fever and dysentery that, he wrote, brought him “to the borders of the grave.” He survived, only to come down with scurvy. The disease affected half of his fellow travelers, killing four. Along the trail from Independence, he said, 1,500 to 2,000 graves dotted the landscape.

Faced with the hard reality of gold mining, McCollum advised that “… all men stay at home and not come here.” He vowed that if he made it home alive, he would be happy with any small employment to make a living.

Ormsby apparently reached California early in 1850. A letter published in the Whig that October described a disillusioning scene: thousands digging for gold; many with meager results to show for the grueling efforts. But Ormsby, an ardent observer of human life, was not disappointed in the trip, finding great worth in presenting scenes, both good and evil, to the people of Ann Arbor in his letters home.

Ormsby’s and McCollum’s cautions failed to deter John Allen. Ann Arbor’s cofounder left early in 1850 with three friends, traveling via New Orleans and Panama. In a letter dated April 30, 1850, he reported that they’d arrived in San Francisco, where he partnered with William Wilson in the search for gold.

By the time Allen wrote home again on August 10, they’d found little success–after three months he and Wilson could not even make $300 between them. In a postscript dated October 24, he added that they had purchased twenty acres outside San Francisco, where they planned to grow vegetables and raise chickens and cows for eggs and milk to sell to the miners. He closed with a note that he had been ill for some days.

It was his final message to Ann Arbor. Allen died on March 11, 1851–the cause was listed as “inflammation of the liver”–and was buried in Yerba Buena.

—

Robert Davidson remained in California but a few months before returning home via Panama. In a March 27, 1850, interview with the Argus, he stated that the “gold in California is inexhaustible.” He made a subsequent trip to the West, returned again, then headed west once more. According to the December 6, 1865, edition of the Grand Haven News, he finally struck it rich in Montana before returning to Michigan and settling in Grand Rapids.

The Downer brothers never returned. They set down roots in one of the richest gold regions in California, Magalia. In 1853 DeWitt sent for his wife and children to join him there. In 1875 the family moved to Condon, Oregon, and James joined them there in 1886.

Samuel Gould returned to Utah in 1849, traveled on to California, and was back in Salt Lake City by January 1, 1851, where he took a second wife. Ever on the move, that November he piloted a wagon train west. In the 1860s Gould visited his first wife in Michigan then returned to Utah for good.

Blackwood, the physician who’d rounded Cape Horn, joined a consortium constructing a dam across the Tuolumne River. They were so sure that they would find huge gold deposits in the riverbed below the dam that Blackwood declined an offer of $50,000 for his share of the venture. But the rains came early, the river rose, and the uncompleted dam gave way.

Blackwood returned to Ann Arbor in the fall of 1850, but the following spring, he packed up his family and returned to California overland. In Sacramento he set up a medical practice but soon died of malignant fever, leaving his wife and four children to return to Michigan.

According to Duff, David McCollum spent little time in the gold fields, and as soon as he possibly could he headed home to Ann Arbor. Running in the spring election of 1851 as a Whig, he was elected justice of the peace for Ann Arbor Township. McCollum spent the remainder of his days in Ann Arbor.

Bidlack writes that one of the three young men who traveled to California under Dr. Ormsby’s wing, his nephew William Barry Mather, died of dysentery in April 1850. His stepson Edward Brown returned home to Michigan. The third, Cyrus Hamilton, stayed in California for years before returning east to enroll in Pennsylvania Dental College. He graduated in 1873 and established a practice in Eureka, Nevada, where he spent the rest of his days.

Ormsby stayed in California for seven years. According to Bidlack, in 1857 he “received news from Ann Arbor that caused him to leave California and start for his old home in Ann Arbor.” Whatever the news was is lost to time, but clutching his small purse of gold dust, he boarded a steamer for Panama; once across the isthmus, he took passage on the Central America on September 6.

According to the Grand River Times of September 30, 1857, a hurricane developed, and the Central America sank two hundred miles off Cape Hatteras. Ormsby was not among the survivors.