Wandering the lines of booths that snake through downtown, the Ann Arbor Art Fair feels like a single vast event. But within it are three separate fairs, each with its own governing board, jury, and territory. And every year, each expresses itself with an original poster and merchandise created by one of its artists. This year is no exception, and all three artists, in their own ways, are exceptional.

Chuck Wimmer: “People Watching”

Chuck Wimmer. | Courtesy of Ann Arbor Summer Art Fair

Ohio digital artist Chuck Wimmer says he’s been coming to the Ann Arbor Art Fair for “at least fifteen to eighteen years.” In that time he’s exhibited in two different fairs, without ever leaving South University Ave.

Wimmer started out in Ann Arbor’s South University Art Fair, which itself took over the street from the Ann Arbor Street Art Fair, the Original when it moved across the Diag. But then the South U fair fizzled, and the Guild of Artists & Artisans expanded its Summer Art Fair around the corner from State St. onto South U. So now Wimmer is a member of the Guild. This year he’ll be selling prints of his digital images in booth SU800—the first one as you turn the corner from State, says Karen Delhey, the Guild’s executive director.

Wimmer is seventy-eight, but says that “mentally I’m going on seventeen.” He always liked to draw, so “I never had to pick a career. … My peers were asking, ‘What am I going to do when I grow up?’ That was never an issue for me.”

He studied art at Kent State University and the Cooper School of Art in Cleveland, then went into the advertising industry as an illustrator. “I had a rep in New York, and we did things all around the country,” he says. “And it was kind of fun that way.”

But when graphic designers switched to computers, “you could buy a disc with three thousand images on it, where you used to have to hire someone like me to do each and every one of those. So the price of illustration just plummeted.”

He had friends who were selling on the art fair circuit. “And they’d say, ‘Man, we made $3,000 or $5,000 this weekend.’ And I’d say, ‘Man, that sounds pretty good.’” So in the early 2000s, he joined them.

Until the pandemic, he did as many as thirty-eight shows a year. “I used to drive to Florida, to Texas, to Minneapolis—pretty much this half of the country.” That “was great fun,” he says, but as he gets older, “I’m getting tired of all the driving.” He’ll do about fifteen shows this year.

He still enjoys the life. “I just like doing shows because I like to say I’m not housebroken anymore. I can’t do as I’m told. I don’t have a boss. I can draw what I want to draw. I can go to whatever shows I happen to get into. And that’s the nice freedom of it.”

For many years now he’s drawn with a stylus on a Wacom tablet. “I can print it to almost any size I want,” he says, but that also means there’s no original to sell, so he has to sell more pieces.

He tries to draw “one cartoon a day and post it” on Instagram (@ChuckWimmer). “Some of them are a little on the risqué side.” Those are also “some of my most popular ones,” he says. “Go figure.”

Birds have been showing up a lot in Wimmer’s recent art. He’s done realistic birds, but in his piece for this year’s Guild poster, “People Watching,” they’re cartoon-like, staring wide-eyed at the viewer. He showed it at the fair last year, where it caught the eyes of the Guild staffers and board members looking for this year’s featured artist.

Of the three fairs, the Guild tends “to be more whimsical with our posters,” says director Karen Delhey. Wimmer’s birds on a wire caught the eye of board members and staffers at last year’s fair. | Courtesy of Ann Arbor Summer Art Fair

Of the three fairs, the Guild tends “to be more whimsical with our posters,” says Delhey. “Last year we had a dog robot. We’ve had a gorilla on roller skates.” In addition to the poster, “People Watching”

will appear on the Guild’s merchandise—“T-shirts, tote bags, stickers, sometimes we do hats,” Delhey says.

That money goes to the fair to support its operations, but as a featured artist, Wimmer does get a free booth. Conveniently, it’s right around the corner from a Guild merchandise booth. When they sell pieces with his work on them, the volunteers encourage the buyers to bring them to Wimmer to sign.

That’s good, because Wimmer’s not a natural at selling himself—“I hate bragging,” he says. He doesn’t even show his face in his official photograph. But this year, he says, when people bring work to his booth to sign, “I’ll feel like a rock star.”

Andy Adams: “Curious”

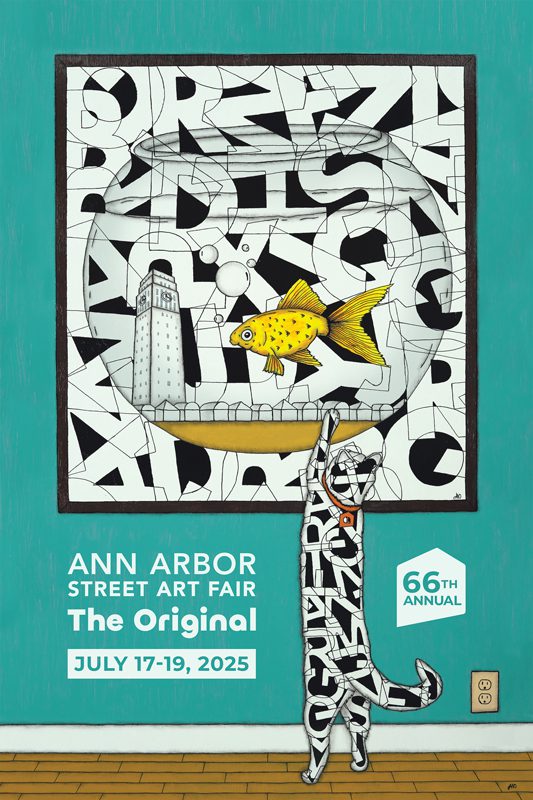

“The poster was my idea,” Adams says, “but I did work with the board to make the piece come together.” Originally, he “was only going to do a goldfish in the bowl with the Burton Tower, but the cat added another layer.” | Courtesy of Ann Arbor Street Art Fair, The Original

“Most people name their art after they paint it,” says Andy Adams, featured artist at the 2025 Ann Arbor Street Art Fair, the Original. “I find words, and then I try to find things that represent the title.”

The title of this year’s poster, done specifically for the fair, is “Curious.” It’s multilayered—a cat pawing at a goldfish bowl, the goldfish eyeing a goldfish-bowl-sized streetscape that includes Burton Memorial Tower (the Original fair’s landmark), and a pattern of hand-painted letters in the background.

Ann Arbor’s oldest fair has the most structured process for selecting its featured artist: “The board of directors go through our group of artists for that year, and we choose ten artists who said they were interested,” says director Angela Kline. Board members visit the artists’ booths during the fair to see, discuss, and rate their proposals. Adams’ concept got the most votes.

“The poster was my idea,” he says, “but I did work with the board to make the piece come together.” Originally, he “was only going to do a goldfish in the bowl with the Burton Tower, but the cat added another layer.”

He calls his work “a way of looking at life. You take a word and make it visual.

“They say a picture is worth a thousand words. That’s kind of what I’m doing.”

Adams usually works in liquid acrylic. “I have to draw out letters first and then paint them. It’s very tedious, and I’m very compulsive. I have to have things in a certain way.

“There are a lot of hidden messages in there. People call my art conversation pieces. That’s literally what my art is: I like to talk to people face to face.”

But like Wimmer, Adams doesn’t like to show his face—in photos, he hides it with his hands. “That goes all the way back to the graffiti thing,” he says. “I do not like representing myself. I want you to look at the art.”

Andy Adams. | Courtesy of Ann Arbor Street Art Fair, The Original

His booth is NU839, on North University next to the merchandise tent. He will have about twenty of his word+image paintings, priced from $650 to $3,000 along with limited-edition “wordcut” prints in the same style.

A South Carolina native, Adams, forty-five, says he didn’t know what he wanted to do in high school. But at Anderson University’s South Carolina School of the Arts, he fell in love with typography.

“My senior year we had to do a big project, and mine was—you know the saying ‘The pen is mightier than the sword?’ Well, if you take the word ‘sword’ and put the ‘s’ on the end, that’s ‘words.’”

It was an aha moment. “That’s where my mind started going—you can move letters around. Words are just letters that we give meaning to.” Since then he’s been “fascinated with going back and looking at the origin of words … how they got their meanings and letters.”

He saw his road ahead, but he didn’t go out on his own right away. “I started working in an ad agency out of school for about five years. … Basically I worked my way over to being just an artist, taking elements of my style with me.”

Adams showed his work in galleries at first. He didn’t even think of art fairs “until a friend of mine talked to me about them and told me how it worked.” He started doing local shows, then went on the road.

“When you first start out, it’s overwhelming. ‘What? I have to pay sales taxes for each state I’m in?’ Now it’s more routine. I feel like I get up and go to a job. There are set hours. You have deadlines.” He’s fine with that.

He’ll do about a dozen fairs this year. Everything he brings is original—a requirement at the Original fair—including the “wordcuts.” After he carves the blocks and makes the prints, he says, he’ll “go back and put spray paint on them—ink, and other things—and they become mixed media.” They’re $60 or $90, depending on the size.

While he loves words, Adams doesn’t consider himself a writer. “My wife says, ‘You always come up with these clever things that most people don’t think about.’” One of them is how he signs his name on his work: “A-N-D.”

“In college I did a little bit of street art, created graffiti, and that was my tag, A-N-D. I thought, ‘What if I make my name sound out?’ That’s why my website’s called ‘The Name is A-N-D.’”

“I like to make people think,” he says. “That’s probably the biggest thing. I want people to think, and have a conversation.”

Brian Delozier: “Michigan in Bloom”

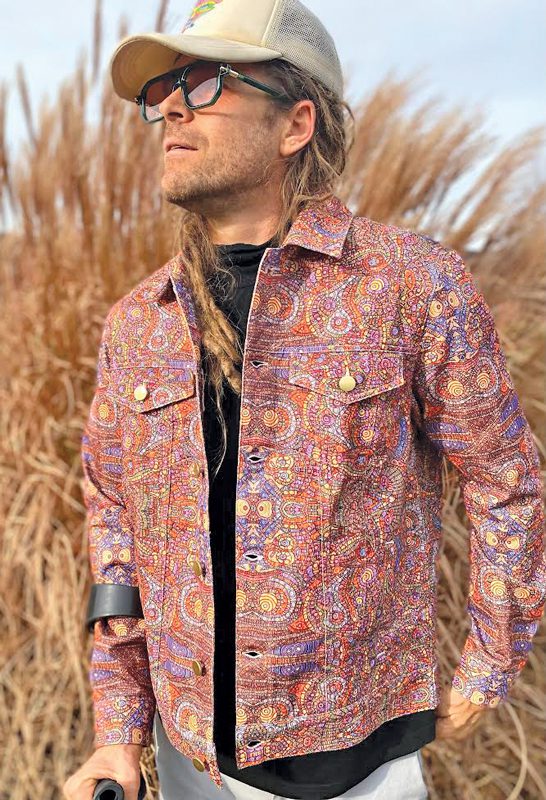

The State Street District Art Fair commissioned Delozier to create an original image for its 2025 poster. A single piece can take six months to complete and contain thousands of dots. | Courtesy of State Street District Art Fair

Brian Delozier’s poster for the 2025 State Street District Art Fair, “Michigan in Bloom,” renders Michigan’s peninsulas in curving patterns of colored dots reminiscent of a field of flowers. You’d never guess that, as he puts it, his “hands don’t really work.”

Delozier was a high school athlete until he took a very bad fall while skiing near his home in Pennsburg, Pennsylvania, north of Philadelphia. “We were just teenagers being crazy,” he says, “flying off jumps, flying down the hills, not thinking about any repercussions. … I ended up getting into an accident and broke my neck.”

In an online essay, his dad, Dave Delozier, recalled meeting with the neurosurgeon who operated on him. “He explained that Brian had pretty much pulverized vertebrae C-5 and C-6. Those were removed, in pieces, and the gap between C-4 and C-7 was fused using a piece of donor bone and a titanium plate and screws. We asked him about the prognosis of Brian’s future abilities and he was very honest with us. He said he gives Brian less than 1,000-to-1 odds that he will walk again, and a 50-50 chance he will regain the use of his hands.”

“I didn’t quite understand how serious a spinal cord injury is,” says Delozier, now forty. He regained “a little bit of function,” but at twenty he was told, “This is going to be something you’re going to deal with for the rest of your life.”

That was his low point. “One day, just sitting there, regretting what happened, wishing it wasn’t this way, and just not feeling any excitement about life or the future or anything, I just said to myself, ‘If you don’t find a way to change your mindset and try to find something in life, this is going to go on indefinitely.’ And that scared me even more than anything that I was experiencing.

“So at that moment I said to myself, ‘Okay. This is how things are in my life. What can I do now moving forward?’ … The last thing I ever would have thought that it was, was art. Making dots.”

Brian Delozier. | Courtesy of State Street District Art Fair

He had enough money saved to buy a one-way plane ticket to Hawaii. “All my friends and family thought I was crazy. They said it was a horrible idea. I could barely walk. I could walk with crutches. But I just felt like I needed some major thing. So I went to Hawaii.

“When I first got there I was still depressed and felt the same way. But shortly after, I ended up meeting this guy a little bit older than me,” an artist named Jason Meloche. “He could tell that I was having a tough time. And he started encouraging me to make art.

“At first I was reluctant. Finally I gave in. I said, ‘Okay.’ I picked up a marker.” He slid it into his permanently clenched right hand and “started making dots. And within a few minutes, literally, I was, like, there’s something special here. I love this. This is going to be my thing.”

At first, he just made rows of dots—it was “peaceful and therapeutic.” But eventually it occurred to him that “maybe I could draw an outline and fill it in with these rows of dots.

“Making a dot picture from start to finish, it totally feels like a big expedition—like climbing a mountain or a long hike. There’s a lot of endurance involved and a lot of things that I experience—highs and lows. A lot of it has to do with focusing on right now, because if I focus too much on the end, or a dot that I made in the past, then it just throws me off. So I really have to stay focused on this moment.”

He works best first thing in the morning. Listening to music or a podcast, “I can really get into a groove, and it’s hard to get out of it. I get into the zone, and I could just make art all day.”

The originals “are matted and framed and put under UV-protected glass. But since it takes so long for me to make the art, I have to charge a lot for it.” So he figured out how to scan his work, “and then in my basement I have some really big fine-art printers. I print it on canvas, stretch it, and frame it.” The State Street fair allows reproductions, and those prints are the main thing he sells here.

Past and interim executive director Frances Todoro-Hargreaves wasn’t involved in Delozier’s selection—she just stepped back into the position in May, when Angela Heflin left unexpectedly—but she does know that the Michigan image was commissioned specifically for this year’s fair. And “they’re giving me a little bit bigger footprint,” Delozier says, “so I’m able to bring some of these bigger pieces.” He’ll be in front of the Dawn Treader Book Shop on Liberty, booths LI532–536.

“I’m actually going to bring ten originals, which will be by far the most originals I’ve brought to any show,” Delozier says. “Some of them are really big and have never been shown in public before, just because I haven’t had the space.”

One is called “Eagle No. 3,” from a series of five he made a few years back. Like the others, it’s very large: two feet by five feet. “There are millions of dots in it, and [creating it] took six months,” he says. A more recent piece, “The Warrior,” is “a big cheetah cat. And there’s this abstract one I finished earlier this year. … It’s just lines and shapes. …

“I’ve been doing this for eighteen years, and I have this collection that I’m really excited about and really proud of, and there are so many different themes,” he says. “So I am at a place where I have the freedom to do that.

“I’m really excited. I feel like this next chapter is going to bring a whole other different side of the art.”

This article has been edited since it was published in the July 2025 Ann Arbor Observer. The name of Andy Adams’ website was corrected.