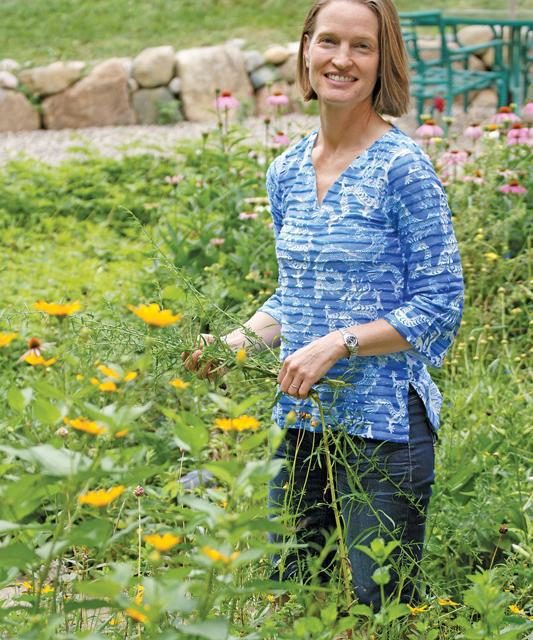

On a hot summer afternoon, Susan Bryan, Washtenaw County’s rain garden coordinator, leaves her office on Zeeb Rd. to deliver some bling to a new master rain gardener. These home visits, she says, are one of her favorite parts of her job–“I love celebrating people’s successes,” she says.

Dressed in a T-shirt, skirt, and sandals, Bryan, a petite and fit forty-seven-year-old, warmly greets Rebecca Nielsen and her two young daughters in Nielsen’s driveway. After attending Bryan’s master rain gardener course, Nielsen turned her front-yard flower garden into a rain garden. A shallow depression collects storm water from her driveway, and a colorful mix of native plants, including blue flag iris, wild geranium, and spiderwort, helps filter it into the soil.

The county promotes rain gardens to “keep pollution out of the river and reduce flooding,” Bryan explains, and to “help mitigate the effect of these more intense storms.” She presents Nielsen with a “Master Rain Gardener” T-shirt and pin, and an official rain garden sign.

Nielsen says the work piqued her neighbors’ interest, and now they want to learn about rain gardens too. Bryan tells me later that it’s a great example of the “ripple effect” she hopes for after people take her class: “People want to hear about it from their neighbors and not necessarily from the government.”

—

When Bryan started her “dream job” seven years ago, twenty people signed up for her first rain garden class. This summer, 180 people registered for her free online “webinar.” Not all students end up planting a garden, but she figures she’s had a hand in constructing about 250 so far.

Students learn how to choose a location that collects runoff from a roof, driveway, patio or lawn and get planting and design tips and plant tips (Bryan suggests a mix of cultivated and native plants; the natives have longer roots). She can make referrals to landscapers if needed, but if people can do the work themselves, she says, “rain gardens shouldn’t really have to cost a thing.” The smallest she’s been involved with, off a condo owner’s patio, measures just one-and-a-half by seven feet. The largest drains most of a one-acre lot.

“She’s so good at the personal interactions–she built a community that works to solve problems,” says her boss, Harry Sheehan, deputy water resources commissioner. He says her “train the trainer” model of peer education has enriched and expanded the program. Governments, Sheehan explains, “can do things on the streets or on a regional scale, but what is difficult is getting into neighborhoods.” Bryan’s celebratory visits, Facebook group, barbecues, and plant and seed swaps help make the connection.

—

Growing up in Lakewood, Colorado, the third of four children, Bryan says she was the one who “tried to keep the balance and the peace.” Her parents always had “the biggest gardens of anyone I knew”–and in their eighties, they’re still at it. But though she shucked corn, snapped peas, and ate the family’s harvest, at Cornell she majored in Asian studies. Her first job after graduation was at the Japanese embassy in Washington, transcribing the Japanese ambassador’s “beautifully written” speeches and giving tours of the Japanese teahouse and garden at his residence. Subsequent stints writing trade reports for a machine tool association, working as a docent at Mount Vernon, and working for a landscape architect were the “trail of bread crumbs” that led her to a career path where she could “get outside.”

She moved to Ann Arbor about twenty years ago to get her master’s in landscape architecture at U-M. She then worked for Pollack Design Associates and for the city, first for the parks department and then overseeing a storm water project.

But being a project manager, she says, “is about making contract specifications so we can’t be cheated by contractors.” She realized that wasn’t for her: “I like the idea of working to bring the best out of people.” She ran her own landscape architecture firm for several years–one of her projects was the Corner Brewery’s courtyard–which had its bumpy spots. Being fired from a few projects, she says, “taught me a lot … you gotta shut up and listen. I learned so much about how to work with people.”

Renee Ringholz, a master rain gardener who lives in the Mitchell neighborhood, planted her first rain garden with Bryan’s help in 2012. “I was amazed when Susan first came to my residence that these consultations were offered for free,” she recalls. “I’ve always thought of Ann Arbor as a forward-thinking, green city, and this … really sealed the deal and made me even happier to live here.” Ringholz went on to create gardens for friends and family members; she just completed her fifth one this year.

—

Bryan met Stephen Hsieh in D.C. at a “cohabitation ceremony” of mutual high school friends. They’ve been married for sixteen years and have a six-year-old son, Hamilton. She says one reason they chose the name was to honor her mother’s hometown, Hamilton, Illinois, where she spent summers as a child. But Hamilton is pleased that thanks to the spectacularly successful musical he now possesses a “famous name” (and the family, Bryan says, has “become obsessed” with the soundtrack).

Hsieh works in IT for Domino’s Pizza. “We can’t even describe what we do” to other people, Bryan laughs. They maintain two rain gardens in their Old West Side yard, and “whenever it rains, it’s a big, exciting event in our family.” She’s proud that her husband and son go out together with their umbrellas “to follow the water to see where it leads–and they clear out any debris they find in storm drains.”

The family bikes together, and Bryan often bikes to work and to the homes of prospective gardeners. She also runs, skis, and plays on two over-forty women’s soccer teams. She’s a midfielder because she “loves to pass, rather than score myself.”

“She’s one of those people who knows how to put people together,” says local landscape architect Shannan Gibb-Randall, who co-teaches the master rain gardener classes. “She’s always trying to think of new ways to improve the program.” Gibb-Randall recalls that Bryan once made forty pounds of homemade Play-Doh–it took her all afternoon–to demonstrate to participants how to “mold the earth” by creating 3-D models of their gardens.

Rain gardens are surging in popularity in communities all over the country, Bryan says. But she acknowledges that not everyone welcomes the wild look in their neighborhoods. (Her advice to the rain gardeners in those situations: plant short and weed well.) But for people intrigued by the idea, she points out that rain gardens, once established, take less work than traditional ones. After all, “You don’t have to water them as much.”

The Zamboni Rain Garden

“We really should call it the Zamboni Snow Garden,” Susan Bryan says with a smile.

One of the city’s largest—and most unusual—rain gardens is next to Veterans Ice Arena. It captures runoff from the ice collected by the arena’s Zamboni ice resurfacer.

During the arena’s September-through-April season, the Zamboni collects and deposits its ice scrapings outdoors at regular intervals. The mounds melt at various rates, depending on the season, but eventually the meltwater runs downhill and is captured by a rain garden designed more than a decade ago by local landscape architect Patrick Judd.

“Patrick Judd served on the design team for a conservation design forum that inspired the city to consider the value of rain gardens,” says Bryan. “His team experimented with a wide variety of plants to determine which are optimal in processing rainwater. If the plants are chosen well, they retain the water so it doesn’t end up in the city’s storm drains.”

Judd and his team affirmed their supposition that native plants are best adapted to the local climate, which ranges from very wet in early spring to hot and dry in the summer.

The Zamboni rain garden has been a tremendous help in channeling water that might otherwise make its way into Ann Arbor’s storm sewers, Bryan says. “It has a unique and difficult job, taking a large quantity of water mixed with dirt, salt, critters, gasoline, and chemicals from the parking lot, and filtering all of those substances out.”

A year ago, Alana Tucker’s U-M graduate class in environmental drawing took a field trip to a local storm-water management project, where she met Catie Wytychak, a county water quality specialist. Wytychak announced she was looking for volunteers for a clean-up day at the Zamboni rain garden, and Tucker signed up.

Wytychak paired Tucker with an older volunteer, Nugget Burkhart. They began working together on the huge garden on Tuesdays and Fridays. Tucker was so inspired that she accepted an internship and then a full-time job as sustainability initiatives manager with the Downtown Detroit Partnership, where she will be responsible for implementing a public rain garden project like Bryan’s. She still plans to continue her weekly weeding at the Zamboni rain garden.

“I learned there was yet another advantage rain gardens offer,” Tucker says. “Nugget has become more than a friend. She’s become a member of my family. The two hours we work on the Zamboni rain garden are often the best two hours of my week.”