Citizens wait to speak at a May planning committee meeting. Comments turned critical when members approved height limits higher those shown at early engagement sessions. | Photo by J. Adrian Wylie

The meeting at the downtown library in May was billed as a coffee hour, but First Ward councilmembers Lisa Disch and Cynthia Harrison turned it into a community engagement session. The topic: the city’s proposed new Comprehensive Land Use Plan.

Development is the hottest button in Ann Arbor politics. In the 2010s, control of council twice swung between the pro- and anti-growth factions that blogger Sam Firke dubbed the Strivers and the Protectors, dislodging a city administrator each time.

That era seemed to have ended as mayor Christopher Taylor and his Striver allies used primary challenges to whittle away the Protector presence. Since taking complete control in 2022, they’d taken a series of steps to make development easier: delegating many decisions to planning commission, removing limits on accessory dwelling units, and approving “planned unit developments” that already effectively expanded the high-rise zone around Central Campus.

The draft plan that was released in April would formalize those changes and go much further, most controversially by allowing multifamily units on what are now single-family lots. There are just under 69,000 housing units in the city, and planning manager Brett Lenart told council in January that the changes might enable anywhere from 30,000 to 97,000 more.

Supporters argue that the city needs that “densification” to allow more people who work in the city to live here, to bolster the property tax base eroded by the U-M’s expansion, and repair economic and racial inequities caused by past “exclusionary zoning.”

Opponents question whether growth on that scale is necessary or even likely. But if it does come to pass, they predict, it will be at the expense of the city’s neighborhoods, as apartments and condos crowd out single-family homes.

Related: Strivers vs. Protectors

At the coffee hour, one attendee seemed clueless about how the city controls development. Others did not know much about the plan but opposed it. Some understood and supported it, and a few shouted at each other. Disch deftly maintained order and squelched rude behavior.

“I hoped that I hadn’t gone a little overboard,” she said later, “but I did notice that they were actually pretty cool after the beginning of the conversation. So that was good.”

Whether any minds were changed is another story. A U-M political scientist, Disch notes that one theory holds that “people form an opinion early on, and they don’t update it when they get new information. … That opinion shapes the later information that they take in, and so it’s pretty hard to move.”

The advocates have been trying. Though state law requires only a couple of months of public engagement before adopting a plan, Disch points out, the city has been reaching out since last summer. By December, a steering committee report tallied “35,000+ website views” and “3,000+ survey participants,” along with nineteen group interviews and seven events at libraries.

According to the report, attendees showed “very strong agreement” in favor of redevelopment near North Campus, along transit corridors, and at shopping centers. There was “strong agreement” on expanding downtown and allowing multifamily “low-rise residential” development in what are now single-family neighborhoods.

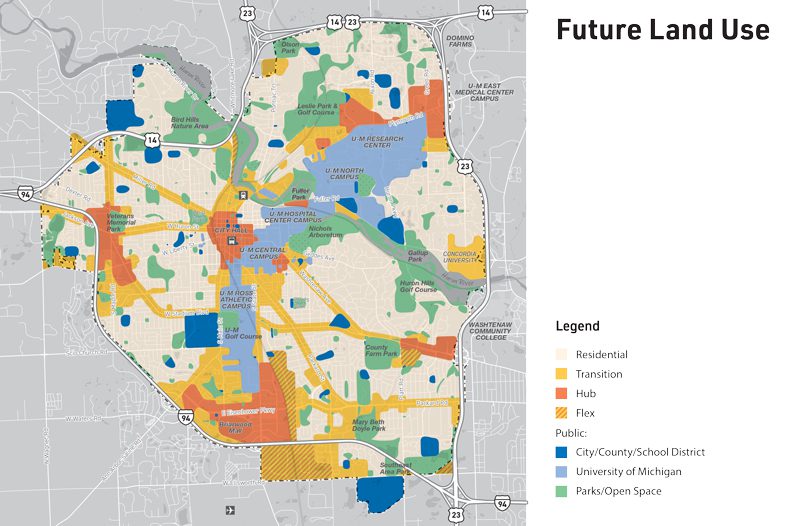

But some participants found what they saw in the materials shocking: buildings up to 300 feet tall downtown, and as much as eighty feet in neighboring areas currently limited to thirty feet. Low-rise residential would see only a slight height increase, to thirty-five feet, but up to four units could be built on each lot. And people had only to look at the included map to see in sweeps of color how their own neighborhood might change.

In the current version, the dark-red downtown “core” expands to the south and east, with a matching one at Briarwood. Next, in orange, are “mixed-use transition” districts, which also radiate out major traffic corridors. Materials shared at the engagement sessions described buildings of four to seven stories there, but senior planner Michelle Bennett emails that she thinks the planning commission has since largely “veered away from prescriptive heights.”

There are pink “employment” districts and strips of red “retail.” But the biggest by far is low-rise residential, its cream color washing over much of the city. It’s there that opposition to the proposed plan is strongest: in the past few months, homeowner groups across the city have created a united network calling on council to “Pause the Plan.”

Residents studied the draft map for clues about how their lives might change. | Courtesy of the Ann Arbor Planning Commission

Mayor Christopher Taylor explains that Michigan law requires cities to review their land use plans periodically. Ann Arbor began the process two years ago.

“The plan is animated by the growing and settled understanding in the community that we have a housing crisis,” Taylor says. “We have artificially constrained housing to the detriment of citizens. It’s all too expensive and we have an affordability crisis; it leads to racial segregation. We want people who work here to be able to live here.”

Former Ann Arbor planning director Karen Hart points out that the comprehensive plan itself won’t change zoning—it will be a “general statement about goals and lays the foundation for future regulations and ordinances that are law.” The current “master plan,” adopted in 2009, speaks in glowing but vague terms of “a dynamic community, providing a safe and healthy place to live, work and recreate … where planning decisions are based, in part, on the interconnectedness of natural, transportation and land use systems.”

In practice, those decisions have also been heavily influenced by residents concerned about changes in their neighborhoods. Unflatteringly known as NIMBYs—“not in my backyard”—they’ve often pressed planners and councilmembers to prevent development near their homes. “And sometimes the NIMBYs prevailed,” recalls Cliff Sheldon, who served on council from 1970 to 1982. Early in his tenure, the city bought 60 acres off W. Huron River Dr. to prevent construction of 240 condos, instead adding it to Bird Hills Park.

In the 1980s, his wife Ingrid Sheldon was on council when it decided to formally foreclose a long-planned extension of Huron Parkway to M-14. While that would have replaced the accident-prone exit on Barton Dr., it would also have given access to an apartment complex that neighbors didn’t want. Ingrid says she “just wanted to keep the option open,” but was outvoted by members seeking “brownie points” with voters. What would have been the right of way is now a series of parks and nature areas.

The Sheldons are moderate Republicans, and in the 1990s, Ingrid was the last of her party to be elected mayor. Her Democratic successor, John Hieftje, was first elected to council on themes of “nature and neighborhoods.”

So it was no surprise when he sided with both over a large multifamily development on the bluff along N. Main St. Planning commission approved it, but when residents just over the hill protested, he engineered its purchase to expand Bluffs Park. He then led the creation of the city’s greenbelt program, which protects farmland and open space outside the city that might otherwise have become new homes or apartments.

Yet he, too, supported redevelopment. When he took office, Hieftje recalls, the city seemed stuck “forever on this decision point: Are we going to try to be a small college town? A medium college town? [Or] are we going to grow a little bit and be a bigger town?”

A downtown residential task force “studied the issue, we got a ton of input, [and] we made a decision to grow,” Hieftje says. “I mean, it was that simple.” Council made it easier to build housing downtown, speeding the construction of what are now more than a dozen high-rise student apartments around campus.

Related: Going Up?

The comprehensive plan would make redevelopment easier citywide.

According to a January presentation to the planning commission, it would cover every foot of land in the city and every major possible use of that land, responding in particular to the need for more housing that is affordable for more people.

In place of the city’s current thirty-four zoning districts, planning manager Brett Lenart explained, “city council specifically directed the plan to consider fewer districts, with more flexibility.”

Wendy Rampson, a former Ann Arbor planner who’s now director of programs and outreach at the Michigan Association of Planning, says similar reconsiderations are “happening all over the country.”

Rampson says Ann Arbor is a “fairly unique real estate market, with the university growing as much as it has. Almost all growth in Ann Arbor since 1970 has been due to the U-M expanding, both in students and employees.”

The university’s expansion in turn drove the construction of subdivisions and apartment complexes on the city’s periphery. Closer to campus, she adds, it “brought the ‘cashbox’ apartments [small, flat-roofed structures on single lots] and the first tall buildings.” Residents disliked them so much that zoning was changed to stop them from spreading.

Fifty years later, some see restrictions as elitist and harmful. Rampson points to a nonprofit called Strong Towns, whose website warns visitors that “a broken development pattern is bankrupting your city and endangering your neighborhood.”

Instead, the group urges planners to “steer your place away from decline and toward prosperity.” City council has already adopted some of the steps it recommends, including making it easier to build ADUs—secondary residences alongside an existing home—and removing itself from most planning reviews. Allowing more multifamily housing would be another.

“People want to be able to downsize here, have their kids come back here,” says Kirk Westphal, a former city councilmember and planning commission chair who now heads the Neighborhood Institute. (Its vision is “Everyone living and meeting their daily needs in the neighborhood of their choice.”) He’s all for the city “simplifying maps and rules, allowing new homes across all areas of the city, and repairing past injustices.”

Westphal was on council during what he calls the “great debate about ADUs” when council divided along factional lines. The resulting compromises limited their development for years, and even now there are only fifty in the city. He cites this relatively minor change as an example of the potential difficulty of making the much larger ones suggested by the draft plan.

Related: ADUs Unbound

A 2016 charter amendment extending council terms to four years has sheltered representatives somewhat from the shifting political winds that once made local politics so volatile. But this year, the winds are rising again.

The December steering committee report, and public comments at planning commission and city council meetings in early February, seemed to confirm that more housing is indeed what the public most wants: increased in number, quality, affordability, and location.

But just a month later, most of the thirty-something speakers at planning commission’s March 18 meeting criticized the draft for having only one zone for housing, citing the desirability of their single-family neighborhoods as they are now.

Tom Stulberg, who lives in the Broadway neighborhood, reminded everyone that “the comprehensive plan is the entire community’s view of what we want for the city. If we blanket zone it all the same, that is giving the market what it wants. We need to account for all different uses of houses. Blanket up-zoning will not work.”

Water Hill resident Bobby Frank remembers people telling him that the Old West Side Historic District was created to stop developers from tearing down homes to build small “quadplexes.” “You have to have some growth,” he says, “but should not change an area very quickly.” Frank doesn’t like the “wind tunnels” around the new high-rises, and doesn’t see how redeveloping only within the city limits can make housing more affordable; that would have to be done regionally, he says.

John Godfrey, from Pattengill, a retired U-M administrator, has been informing existing neighborhood associations about the proposed changes and helping organize new ones. He says his opposition begins with a deep appreciation for “really engaged participatory democracy, building consensus, making tradeoffs that all understand, while knowing we can’t agree about it all, using appropriate ways to make decisions.” If the plan is approved, he says, we “run the risk of replacing what is left of our affordable housing with higher cost rentals.”

Minneapolis is five years ahead of Ann Arbor: in 2020, its Minneapolis 2040 plan took effect, making it the first large city to eliminate single-family zoning citywide. The plan allows duplexes and triplexes everywhere, expands the zones where housing could be built, permits greater density downtown and along transit routes, and eliminates off-street parking requirements for new developments. Last year, an analysis by the Pew Charitable Trust found that “from 2017 to 2022, Minneapolis increased its housing stock by 12% while rents grew by just 1%. Over the same period, the rest of Minnesota added only 4% to its housing stock while rents went up by 14%.”

Though the period started before the city’s plan took effect, by 2017 parking minimums had already been eliminated for building near high-frequency public transit. There are several prominent examples of new, large housing projects with much less parking than would previously have been required.

Early this year, however, Ann Arbor’s plan hit a speed bump. During the engagement process, Disch says, the consultant and planning staff had, atypically, assigned height numbers to the new districts. But commission had never given direction on that, and when the question came up at the January meeting, “We said, ‘That’s only five feet taller than what currently exists. That doesn’t seem like a meaningful increase,” Disch says. “We can make a lot more efficient use of land if we allowed four stories, which would be forty-eight feet. … I voted for that at the time.”

But once word got out, “there were people who’d been in those sessions who objected,” Disch says. “And then there were many other people who just woke up and said, ‘Whoa!’” Then the opposition group produced a flier with a picture of a five-story—“not a four-story, but a five-story”—apartment “built right up to the side lot line, so that it was right up against a detached single family home next door. …

“It was an extremely manipulative and fear-inducing communication, and it got a lot of people’s attention.” Many of them were “putting yard signs and signing a petition to ‘pause the plan.’” It seemed that fear had gained a foothold on the issue, and she “wanted to defuse it.”

Disch raised the issue with her fellow planning commissioners, who “declined to take it up.” But in her dual roles as a councilmember, she raised it again there—and with backing from Taylor and others, council politely requested that the planning commission reconsider. The planners politely agreed, capping low-density residential at three stories.

Related: Building Faster

“Ithink the planning commission is probably more gung ho on this than the council is at this point,” Hieftje says. “I think the council is hearing some feedback and saying, ‘Okay, let’s back off a little bit.’

“I don’t know if that’ll be enough of a back off.”

The former mayor lives on a mixed homeowner-student renter block in Burns Park and says it’s fine. But he sees no rush to redevelop single-family neighborhoods when there’s still untapped potential in the new, super-dense transit corridor zones.

The opposition, meanwhile, has coalesced around the campaign to “Pause the Plan.” An online petition cites “unrealistic projections” for population growth, “hidden costs” for new infrastructure if they are realized, and “inadequate public engagement.”

It got a boost when townie and best-selling author John U. Bacon called it to the attention of his nearly 80,000 social media followers. Bacon messages that he “can’t recall when I first became aware of it. … But when I looked at it more thoroughly, I was surprised how aggressive it was—and more important, as I learned more, likely unproductive on the very goals the [plan] is intended to achieve.” As the Observer went to press, Godfrey reported that more than 2,500 people had signed their online petition.

Lenart himself has cautioned that the city’s ability to achieve any particular outcome is limited. For example, “we cannot control what happens to the national economy.” Planners also “need to be mindful of the potential to over-regulate as well as the potential to miss opportunities for influence.”

Bennett emails that the recent edits are now “being incorporated into the next draft.” Though it was too soon to say at press time, she writes, it “could be quite different.”

The next draft and map should be delivered to the planning commission and council this month. A new window for public engagement will open when it’s released, and another when it reaches council for a vote.

Already pushed back from this spring, that deadline has now been delayed again—but only from November to December. That gives Ann Arbor six months to decide how it feels about growth.

This article has been edited since it was published in the June 2025 Ann Arbor Observer. Corrections were made to the spelling of Cynthia Harrison’s name and the number of signatures for the Pause the Plan petition.

Calls & Letters June 2025: Cynthia Harrison & Petition Signatures

In our feature on the city’s proposed new comprehensive plan, we lost the final letters of Cynthia Harrison’s last name somewhere in our production cycle, reducing it to “Harris.” Our apologies to the Ward One councilmember. Our apologies as well to plan opponent John Godfrey. In the same article, we inexplicably doubled the number of signatures he reported for their online petition to “Pause the Plan”—it was 2,500, not 5,000! The petition “now has the names of over 3,000 actual residents,” Godfrey emailed in mid-June. “And, unlike the city’s unscientific ‘surveys,’ these individuals are not double-counted.”