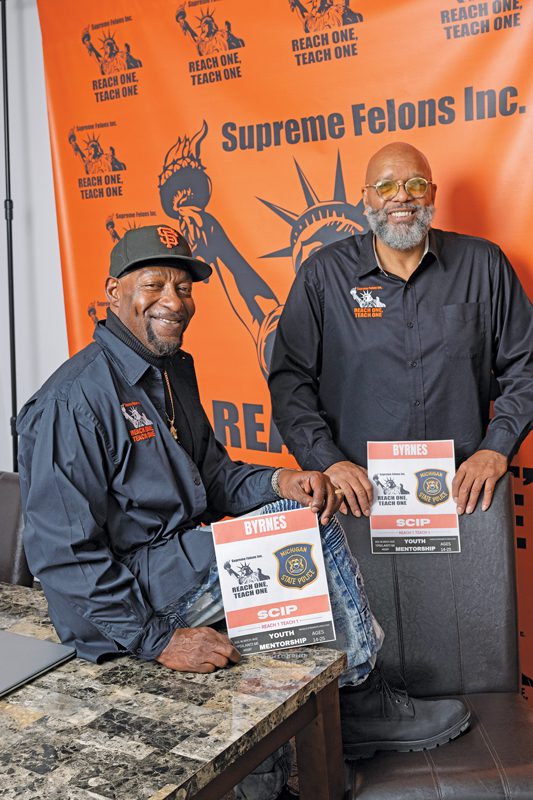

Inspired by the peer-to-peer mentorship he received through the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Office, Billy Cole (left) teamed up with Bryan Foley to create Supreme Felons. | Mark Bialek

After forty-three years, eleven months, and twenty-three days, Billy Cole was released from prison. It was 2019 and he found himself scrambling, trying to find his footing. He took on factory work, delivery work, anything he could find to bring in money and avoid returning to prison.

But it was his work with the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Office (WCSO) that helped him understand a major mental hurdle to his successful reentry to society: “collateral damages” to his identity from being in prison. After confronting those collateral damages with other returning citizens through WCSO’s peer-to-peer program, he got to work in the community, where, he says, “my purpose, my target, was recidivism.”

Billy Cole is now the executive director of Supreme Felons, Inc., a community mentorship and life skills program for young people who need support and for Washtenaw County returning citizens. “I understood that there’s a deeper level than what the typical social worker and professional would know in terms of returning back to society with collateral damages,” he says.

The same year Cole was released, funds from Washtenaw County’s Public Safety and Mental Health Preservation Millage, passed in 2017, became available. The millage was voted in at a two-to-one margin, despite its last-minute addition to the ballot. In 2024, voters renewed it with about 70 percent of the vote, ensuring funds until 2033.

About $15 to $18 million per year, and rising, is divided between the WCSO, Washtenaw County Community Mental Health (WCCMH), and independent police forces in cities and townships, funding efforts that improve public safety and mental wellness. Initiatives include interrupting cycles that lock people up for addictions and mental health struggles and offering evidence-based solutions and treatments instead. WCSO’s Mental Health Criminal Justice Diversion Advisory Council notes that the recidivism rate for inmates with mental health and substance use disorders was 58 percent in 2017, almost double the rate for the general population.

Washtenaw County Board Commissioner Andy LaBarre helped author the millage. He says that while it grew from concerns over budget increases that weighed on townships and municipalities, it also grew from collaboration. LaBarre notes that WCCMH and the WCSO had been working together for several years “in tandem, trying to understand how their service populations overlapped.”

The offices launched a data evaluation process, called sequential intercept mapping, especially designed for capturing criminal justice and mental health interactions.

“We did a mapping of the whole continuum of how people enter and leave the criminal justice system. That’s from the first point of arrest all the way through the court system,” explains WCCMH executive director Trish Cortes. It showed “where our strengths were and where we had areas of opportunity … kind of an inventory of what we currently have and what we need to be more effective in diverting and deflecting individuals out of the criminal justice system.”

WCCMH and the WCSO each have a set of initiatives attached to the millage that improve public safety and mental health supports, like rethinking emergency responses to divert people away from jail and into mental health treatment instead, supplying supportive housing, and mapping pathways for youth away from juvenile detention and into support.

Cortes says that the Co-Response Unit (CRU) is an especially successful program, where master’s level social workers are paired with a police officer in a very lightly marked patrol car for crisis responses. She adds that they’ve had “success stories that are really, really, really phenomenal with incredible outcomes.”

Related: An Afternoon With Community Mental Health

The teams have gone into the community and forged relationships, supplying staples from granola bars to hygiene supplies to community resources before need-based frustrations lead to crime. In one instance, a team engaged “with an individual who was also experiencing homelessness and addiction and [they] developed a relationship with that individual” through repeated contact. They were eventually able to connect that person to a long-term addiction recovery program that matched their needs.

Reports from the Michigan Department of Corrections show a slight downtrend in recidivism rates in Washtenaw County: 29.3 percent of parolees released in 2021 returned to prison within three years, down from 33.6 percent the year before. But connecting recidivism rates with specific initiatives is historically difficult—factors are layered and complicated. And when the incarcerated population in Washtenaw County is over 50 percent Black when only 13 percent of the overall population is Black, there’s systemic racism at play in every pipeline.

Back to Billy Cole. After he participated in reentry programming with the WCSO, he sought out even more formal ways he could help others. He says that “within our community, a small number of guys—and Bryan Foley was one of them—were actually doing work to prevent recidivism.” So Cole and Foley combined forces and followed the work of other community leaders like Harry Hampton and Bernard Cook, who “set the platform for us,” and incorporated Supreme Felons in 2020, a year after his release.

Bryan Foley is at the center of the Ypsilanti community. A local electrician with his own company, he’s on the board of the Ypsilanti Downtown Development Authority and runs his own community-centered podcast called Ear to the Ground 197, which hosts guests like Debbie Dingell. He also spent time in prison.

Foley and Cole ran Supreme Felons from 2020 to 2022 with the support of individual donations, a couple of grants from Ann Arbor Area Community Foundation, and a small grant from Community Mental Health of Southeast Michigan to help prevent the spread of Covid—they distributed masks, test kits, and information.

“We weren’t thinking about no funding. We were just thinking about doing,” Cole says. “We were making contacts and collaborating with people because we needed their help to help our own community. Well, there were some officials that were paying attention to us.

In 2022, Foley says, the Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners approached them and told them that they were “doing the work that fit the criteria of this [ARPA] grant,” says Foley. The board wanted to award the Supreme Felons a three-year American Rescue Plan Act grant, which intended to help organizations develop “ambitious projects. They accepted.

With financial support, their outreach only grew, and they were able to secure an office space and about six part-time employees. Every day, Cole works to prevent others from taking the same road he did at eighteen, when he went to prison after robbing a convenience store and shooting and killing a young employee. It’s always there, he says, the “harm that I caused. … It wasn’t just me. I affected an entire community.”

Since late 2022, Supreme Felons have delivered services to 465 returning citizens. Even against the county’s recent low of 29.3 percent, Supreme Felons’ recidivism rate stands apart. They report that only four people, or less than 1 percent of their clients, have returned to prison after three years.

Cole and Foley attribute this to their “special sauce,” which is made from a community and “boots-on-the-ground” work. Cole tells their clients, “If you tell me you want to stay out of prison, we’re going to help you. … I can fill in the gaps of what you need. If you’re on medication and need attention for mental health, I can point you in that direction. If you are dealing with a substance of any type, we got these guys here that’s experienced in substance abuse. … If you just want someone to talk to, here’s my personal telephone number.”

He and Foley walk the neighborhood and recruit businesses to hire returning citizens. When they know violence is in the air, they reach out, sometimes touching base nightly with someone by phone until the tension moves on. A few years ago, when gang-related gun violence was especially high, they brought gang leaders literally to their table and brokered a truce.

Related: Life After Prison

They even answered a call to patrol a high school basketball game after hearing rumors of gang violence. They showed up “suited and booted” and kept the game peaceful.

“Community violence interventions keep [young people] separated from law enforcement and the jail,” says Foley. “What we mean by that is, if we can get to them before a potential act of violence … and have a conversation with them, right there,” he and Cole can make a difference that could be lifesaving.

Cole calls their community advocacy for nonviolence their “umbrella”—a protection from harm.

Sheriff Alyshia Dyer speaks at the county’s first IGNITE graduation in October. Nine incarcerated individuals were awarded GEDs at the ceremony. | Courtesy of WISD

Flint’s Johnell Allen-Bey felt education could be essential to his and other’s reentry process. During his time in prison, his bunkie was Aaron Suganuma—now a key force in Washtenaw County’s reentry programs, and also a mentor to Billy Cole when he was in peer-to-peer. (To complete the circle even more, it so happens that Allen-Bey and Cole have known each other since they were teens.) In prison, Suganuma and Allen-Bey discussed ways they might help others after they were released; for Allen-Bey, it came down to education.

He worked for years after his release to set up education programs for those in prison. Allen-Bey eventually joined forces with Genesee County Sheriff Christopher Swanson to start IGNITE in 2020, a program that’s just been adopted by Washtenaw County as well as by 3,084 sheriff’s offices through the country, from Texas to Minnesota.

The program provides incarcerated individuals with education, job certification, and post-incarceration opportunities and assistance, what Billy Cole calls “the light of opportunity.” According to a Harvard study, IGNITE is remarkably successful, reducing one-year recidivism rates by 23 percent.

A few years after Allen-Bey and Genesee County Sheriff Christopher Swanson implemented IGNITE, they met with then–Washtenaw County Sheriff Jerry Clayton to talk about implementing IGNITE. Now, with Sheriff Alyshia Dyer on board, the work continues. The county held its first IGNITE graduation in October, delivering GEDs to nine incarcerated individuals.

Related

The Next Sheriff: Alyshia Dyer won the August Democratic primary by a slender 384 votes.

Dyer says that IGNITE has improved the environment within the county jail and provides inmates with “real career pathways so they can … have a better life.” She also notes that reducing recidivism creates a safer community for everyone.

“Making sure people have pathways to success isn’t just improving public safety,” she adds. “It’s improving the humanity, it’s improving people’s quality of life, their children, their families. … It has a cascading positive impact on the overall community, and our mission to build a safer, more just, and compassionate community is right in line with that.”

Programs like IGNITE and millage-based initiatives continue to grow through county funding. Meanwhile, Supreme Felons have passed the three-mark of their ARPA grant and are searching for new funding. But they continue to do the work. They are too aware of the need.

“’Cause when you hungry, I’ve been that hungry, so I understand it,” says Foley. “So I’m empathetic to the hunger.”

Cole adds, “You know we’re going to hold you up.”