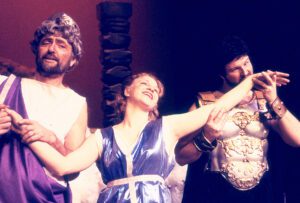

Tom Petiet (Jupiter), Juliet Petrus (Eurydice), Jeff Willetts (Pluto) in Orpheus in the Underworld.

In 1963, a fellow U-M art student heard Tom Petiet singing while working in class and suggested that he audition for the U-M Gilbert & Sullivan Society (UMGASS). It was a life-changing experience for the young artist, who sang his way through the G&S canon, often in leads, and met and married Pat, a dancer who performed in the UMGASS chorus.

Petiet loved the combination of music and humor, “the way pompous characters and sacred cows of all sorts could be skewered”—not only in G&S, but in less-well-known operettas of Offenbach, Strauss, Lehár, and others. He had done most of the G&S repertoire, and he and some friends decided to form a new company to do more varied work. “Comic opera has a lot to offer. It’s musically sophisticated and a lot of fun,” Petiet reflects.

The Comic Opera Guild (COG) was born.

They planned to launch in 1973 with John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, making extensive plans the summer before. As they began casting, the music director said he was moving to New York. They couldn’t do the show without him, and COG almost didn’t get started.

But start it did that year, with one-acts by Mozart and Gilbert. And they lost their shirt. A $2,000 shirt. “That could have been the end right there,” Petiet reflects.

The next offering, a dinner theater production of Cox and Box, netted $1,000. Instead of putting it toward the debt, they used it to seed a large production of Die Fledermaus. “It looked like a complete disaster during rehearsal,” Petiet recalls. Not everyone remembered lines or cues.

“One chorus member dropped out because he didn’t want to be embarrassed,” Petiet says. But it came together “magically,” succeeding artistically and financially.

—

Karin White (Rosalinda), Mitch Gillett (Eisenstein) in Die Fledermaus.

Since then, COG has revived and performed 100 different operas and operettas. Its shows have toured throughout the state, with a full cast, orchestra, sets, and costumes—something few companies anywhere can do.

“The Michigan Opera Theatre tours with just a few singers,” Petiet notes. “I have always felt, and still do, that the risk in innovation and originality is necessary to breathe new life into a neglected art form, just as l have felt that touring, while not absolutely necessary for survival, created excitement and interest in what we were doing.”

But these days, it’s hard for COG to tour. “People aren’t coming to theater the way they used to. Electronic media has changed the landscape,” he laments. In the late 1980s, COG shows could fill the Michigan Theater; today, smaller venues usually have to suffice.

Fundraising has seen highs and lows, too. “We had fairly decent grants from the state of Michigan until Engler, the newly elected governor, cut arts funding to the bone [in 1992]. We had to struggle past that and develop our own group of donors, and we had to do some shows that could make money.”

To make ends meet, they stored and reused costumes and sets—a couch acquired for Fledermaus has so far appeared in seventeen shows. And they remained an amateur company, casting folks with day jobs who didn’t get paid for their work with COG.

—

Daniel Schuetz (Eisenstein), Jennifer Bird (Rosalinda) in Die Fledermaus.

Petiet learned to sing by listening to records, so recording became a priority for the Guild—“We wanted to preserve our original shows.” In addition to creating an archive, they’ve made money selling recordings, at first reel tapes, then cassettes, and now CDs. They sell to collectors through the internet, as well as through dealers in Connecticut and Germany. The Guild has recorded sixty-

eight early Broadway shows.

All COG shows are sung in English. “The greatest operettas were European, the same as operas,” says Petiet. When there is no good English translation, they do the translations themselves. Over the years, COG has created new English performing versions of twenty-one European operas and operettas that are available to other companies.

Performers who have appeared on the COG stage say they’ve grown from the experience. “Never in a million years did I ever think that, someday, I’d be performing in a live opera on a stage in Ann Arbor,” says Tom Skylis, a retired administrator at the VA Medical Center and a longtime COG chorus member and current board member. “COG has given all of us the opportunity to push ourselves into roles that might have been a bit out of our comfort zones.” Skylis says the Petiets have “given us, and the viewing public, fifty years of performance magic.

They’ve given opportunities to upcoming artists, too. For more than twenty years COG organized the Harold Haugh Light Opera Vocal Competition for young performers who prove they can act as well as sing. After awarding more than $70,000 to young singers, Petiet emails that the competition is currently “undergoing a sponsorship transition.”

—

The Guild had to cancel a production mid-run when Covid hit in 2020. After recording two Victor Herbert shows during the pandemic, it will be back on the boards in 2024 to celebrate Ann Arbor’s bicentennial. In late January, they will present their own restoration of Evangeline, a parody of the Longfellow poem by J. Cheever Goodwin and Edward Rice. The first comic opera by American authors, the semi-staged concert will be in the Riverside Arts Center in Ypsilanti.

In May, they’ll be back at the Michigan Theater to do a concert honoring Victor Herbert, dubbed “the father of the Broadway musical,” on the 100th anniversary of his death. COG will do Herbert musical numbers they discovered and revived, now with restored orchestrations.

In addition to the pleasure it’s brought to audiences, Petiet points out, “the work of the Comic Opera Guild is also a history of the development of the comic opera and the subsequent musical theater.”

If it never existed, some COG performers might not have gone on to professional careers. “An old lady in Niles would not have seen her favorite operetta before she died. And fifteen couples would never have married.”