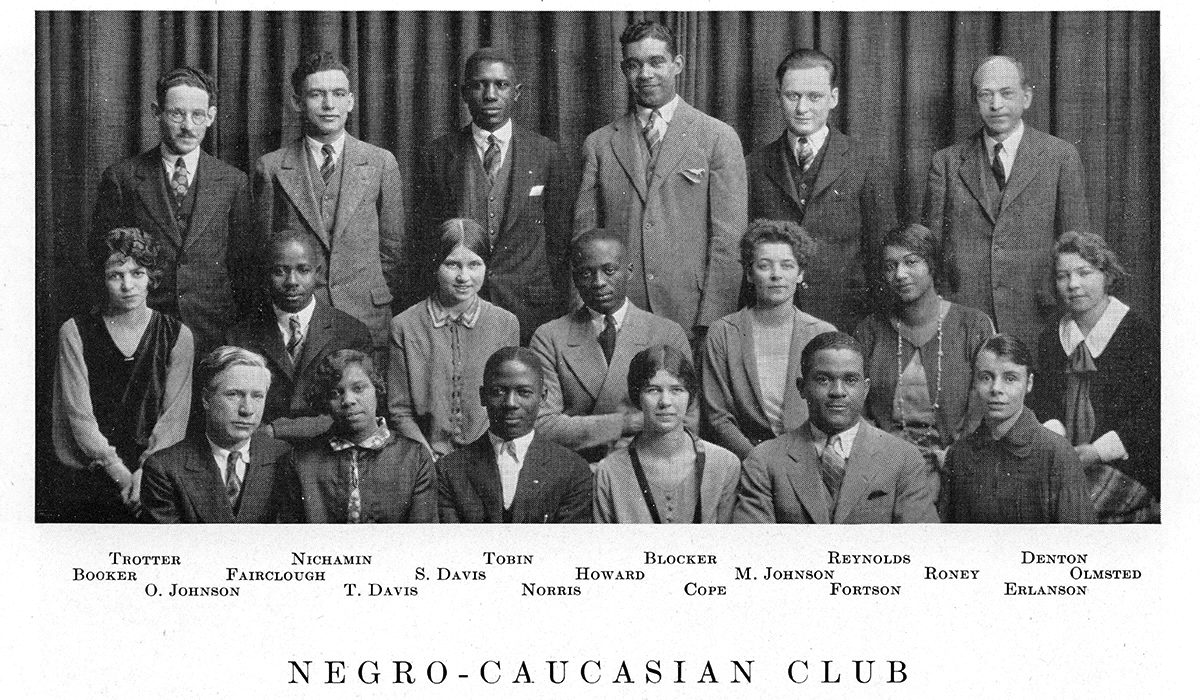

Though it was formed in response to a racist incident in a campus-area restaurant, the Negro-Caucasian Club was told its bylaws couldn’t call for the abolition of racial discrimination. | Photo courtesy of U-M Bentley Historical Library

On one autumn afternoon in 1925, two U-M students stopped for lunch at a restaurant in Nickels Arcade, but no one came to take their order. After a long wait, a busboy approached them with a stack of dirty dishes and placed them on the table.

As one of only sixty African Americans among the university’s 10,000 students at the time, Lenoir Smith needed no introduction to racism. Her friend and classmate Edith Kaplan, however, was outraged when she realized what had happened. That demeaning experience became the pivotal point in the creation of the Negro-Caucasian Club.

Black students had shared classrooms with their White contemporaries since the 1860s, but that is where integration ended. Swimming pools and college dances were off-limits to the Black students. Black men mostly occupied one of the three Black fraternity houses: Kappa Alpha Psi, Omega Psi Phi, and Alpha Phi Alpha; the rest lived in segregated boarding houses or found accommodations within Black households. While White women had access to university dormitories, the few Black women were referred to private boarding houses off campus.

It was under these conditions that Smith, Kaplan, and rhetoric instructor Oakley Johnson organized the Negro-Caucasian Club on December 7, 1925. Its mission, in the words of its constitution, was “to work for a better understanding between the races and for the abolition of discrimination against Negroes.” The members numbered twenty-six, made up of twenty-one Black students and five White.

But when the members requested recognition as an official student organization, they were informed that “provisions of the constitution should be modified” before the group would receive the school’s stamp of approval. The unacceptable provision? Calling for the “abolition of discrimination against Negroes.” Racial justice was not on the university’s agenda.

The constitution was revised with vaguer language, and after mulling it over, the Committee on Student Affairs gave its consent on March 26, 1926. However, the recognition was for one year only, and Johnson was cautioned that “the name of the University of Michigan shall not be used in connection with the activities of the Club.”

The Ku Klux Klan was resurgent in the 1920s, electing governors, congressmen, and senators around the country. In that atmosphere, the cautious committee members may have felt vindicated when the Negro-Caucasian Club made what at the time were perceived as brazen demands, including organizing sit-ins at local restaurants.

On campus, the resentment aimed at both Black and White students was palpable, and it wasn’t just coming from university administrators. The club’s White members and faculty advisors embraced Black students as equals, and some faculty members, such as biology professor Lewis Heilbrunn, disputed racist assertions of Black inferiority. But to other faculty members, the racial integration the club advocated was an anathema.

In his book Life and Labor in the Old South, professor Ulrich B. Phillips, a member of the history faculty, espoused the belief that slavery was “paternal and kindly,” and slaves had recognized it as such. A science department colleague, A. Franklin Shull, advocated the racist philosophy that would soon be made infamous by Adolf Hitler, asserting that people of Nordic ancestry were innately superior, while those of African descent ranked far lower in natural aptitude.

Guest speaker Alain LeRoy Locke spoke on prejudice in literature. | Photo courtesy of U-M Bentley Historical Library

The Negro-Caucasian Club countered those degrading beliefs with a lecture series featuring Black intellectuals. U-M French professor R.C. Trotter’s address on “Foreign Problems” put special emphasis on the situation of people of color living in France, who experienced better conditions than those in the United States. Howard University professor Alain LeRoy Locke, “the Dean of the Harlem Renaissance,” discussed prejudice and literature. Toledo University’s J. Sylvester Gould addressed “Racial Superiority and Inferiority.” The high point of the series was a visit by none other than W.E.B. Du Bois. The renowned scholar, writer, activist, and NAACP cofounder spoke on racial segregation in the Natural Science Auditorium.

Another guest speaker was A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who denounced what he described as rampant corruption among large corporations. Almost forty years later, Randolph would help organize the 1963 March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. declared, “I Have a Dream.”

The Negro-Caucasian Club wasn’t the first campus organization to advocate for Black students. The Colored Students Club was organized in 1902, with the goal of aiding low-income Black students. Its founder, law student Eugene Marshall, told the Michigan Daily they faced “a prevailing discrimination against the race in boarding and eating places.”

The Colored Students Club helped students find employment, housing, and medical treatment. A system for handing off used textbooks from one class to the next was particularly appreciated. But the association lacked any wider influence. Faculty members and White students paid it little mind. The Black students were on their own.

In contrast, at least half the members pictured in the Negro-Caucasian Club’s photo in the 1927 yearbook appear to be White. About sixty were listed, along with several faculty advisors. Yet when club president Lenoir Smith again approached the university seeking permanent standing that year, renewed temporary status was all the club was accorded and that again for only one year.

The group was known to have a leftist bent and suffered for it. Oakley Johnson, their faculty advisor, was a Marxist. As an untenured lecturer, his politics and activism derailed his academic career. A veto by a conservative professor delayed his doctorate by a year, and his department’s promotion recommendations were relegated to the trash bin. Johnson left the university in 1928.

The Negro-Caucasian Club held on until 1930, then faded into oblivion as the founders moved on and the Great Depression enveloped the entire country. But its members went on to leave their mark in the world.

Lenoir Smith, whose humiliation at the restaurant sparked the club’s formation, led the serology department at the University Hospital starting in 1953; she held that position until 1958. Edith Kaplan signed on at the University of Chicago as an expert on ancient languages.

Julius B. Watson was employed with the Detroit Office of Economic Opportunity. William M. Howard became a successful attorney in Youngstown, Ohio, while James R. Golden ran a firm in Battle Creek, Michigan. Clarence W. Norris became dean of St. Philip’s College in San Antonio, Texas. Armistead S. Pride chaired the Department of Journalism at Lincoln University, a historically Black school outside Philadelphia.

Pride would later recall how the club “helped relieve the Negro student’s feeling of isolation,” served “to give him some portholes onto campus life other than those of the classroom … [and] helped to lay the foundation for larger civic and institutional efforts that led to social and civil rights legislation in the sixties.” And that is saying a lot of a small club with temporary status and only a five-year lifespan.