For most of the twentieth century, it was nearly impossible to see films other than current Hollywood releases in all but the largest cities. In Ann Arbor, however, student-run groups filled the gap mightily. This article, adapted from Uhle’s 2023 book Cinema Ann Arbor, describes the birth and evolution of the largest and longest-lived, Cinema Guild.

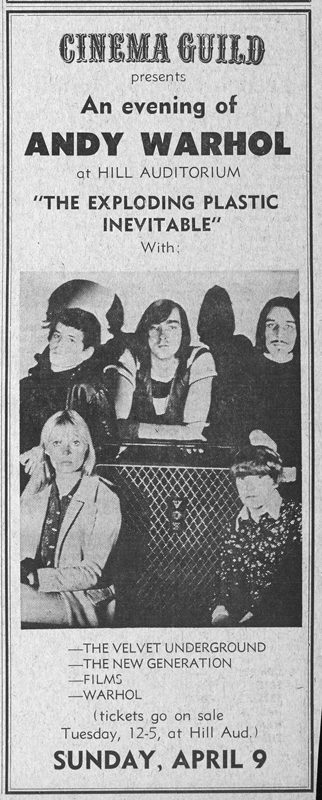

Showing as many as ten films a week during the school year in the Architecture Auditorium (now Lorch Hall), Cinema Guild cosponsored the Ann Arbor Film Festival from its start in 1963 and hosted guests like Frank Capra, Harold Lloyd, Andy Warhol, and the Velvet Underground. And it sometimes courted controversy with screenings of banned films like Flaming Creatures, which in 1967 led to the arrests of four Cinema Guild board members.

Students hear from maverick director Sam Fuller at the Architecture Auditorium. | Photo by Jay Cassidy

The first film society at the University of Michigan was the Art Cinema League (ACL). Founded in 1932 to take over the intermittent film programming begun at the Michigan League by Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre manager Amy Loomis in 1929, it was one of the earliest campus film groups in the nation.

At the time, the W.S. Butterfield Theatres chain had a monopoly on Ann Arbor’s half-dozen movie screens, and its famously conservative local manager Gerald Hoag saw little need to provide anything but the latest from Hollywood. The ACL brought to campus the foreign films, documentaries, historical retrospectives, and other artistic pictures that Hoag ignored. While Butterfield was showing the latest Shirley Temple or Rin Tin Tin movie, the ACL might be screening Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion and a program of early silent films from the Museum of Modern Art.

These proved so popular that, after a brief hiatus during World War II, the ACL began to share the bulk of its profits with campus organizations that cosponsored screenings. But it soon faced new competitors like Butterfield’s Orpheum Theatre on Main St., which in 1948 began offering “the finest film importations from all nations” on weekends, and the Gothic Film Society, founded a year later to provide monthly members-only screenings of significant older films in the Rackham Amphitheatre.

In 1950, key members graduating and fading interest among those remaining left the ACL rudderless. It turned to the university for help, and that fall was reconstituted as the Student Legislature Cinema Guild, overseen by a four-person board. Paid manager and English grad student Richard Kraus chose the films, and the Student Legislature took a cut of the proceeds.

Cinema Guild made its debut at Hill Auditorium on the weekend of October 13–14, 1950, with David Lean’s Great Expectations, and carried on with weekend-long bookings of a single feature. Along with imports like Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief and Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky, Kraus also showed recent American hits like John Ford’s My Darling Clementine. There were special events as well, like the campy “A Night at the Flickers” silent double feature of Tillie’s Punctured Romance starring Charlie Chaplin and 1925’s The Eagle, with one “Professor G” providing live piano accompaniment.

Groups ranging from the Displaced Persons Committee to the Rifle Club still lined up to take 80 percent of a weekend’s profits. But Kraus also wanted to get closer to the group’s original artistic mission.

“The university is a cultural center, hence the few movies that are worthy of attention in any given year should be shown here as soon as possible,” Kraus wrote to the Michigan Daily in February 1951. “If we can show them without putting ourselves in financial jeopardy we feel it our responsibility to do so.”

His efforts paid off a few weeks later when Cinema Guild presented what it proclaimed to be the first U.S. screening of Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus outside New York. Kraus told the Daily: “I really had to mortgage my soul to get it.”

The group soon adopted the 400-seat Architecture Auditorium as its permanent home, even as some complained about the hard seats and mediocre image quality. In 1953, the film society installed a larger screen and new projectors, the first of many upgrades. Its schedule was also expanded to two features per week, each for two nights.

In 1955 the U-M Student Legislature was superseded by the newly created Student Government Council. Though still subject to oversight, Cinema Guild would no longer contribute to its funding, which was instead drawn from a 25-cent-per-semester contribution from tuition. That February the film society celebrated the sale of its 200,000th ticket.

But soon a new commercial competitor opened just a few blocks away. In March 1957 the Butterfield chain closed the Orpheum and unveiled the new 1,054-seat Campus Theatre on South University Ave. Touted as having “the latest in sound projecting equipment and refrigerated air conditioning,” the stylish venue began programming a mix of imported comedies, occasional Hollywood blockbusters, and current art releases like Federico Fellini’s La Strada.

With European films in particular beginning to show a new openness about sex, for some titles the Campus Theatre inaugurated an “adults only” admissions policy. But Butterfield remained sensitive to public pressure, and in early 1958 Hoag ended a run of the Swedish film Time of Desire after one night due to complaints about an implied sexual relationship between two sisters.

Students line up to buy tickets to a Cinema Guild show. | Michiganensian Yearbook

At the same time, Cinema Guild’s board was beginning to chafe at the demands of cosponsors. Manager Ed Weber had started inserting edgy experimental shorts by the likes of Stan Brakhage before features, which sometimes caused a backlash from outraged attendees, and when Time of Desire became available for campus bookings the film society jumped on it. Advertised as “A Young Girl’s Haunting Initiation Into the Mysteries of a Strange Love!”, the May 1959 screening attracted “crowds of stag males,” Faith Weinstein reported in the Daily. She noted that “the film was delicate and well-handled. It sold because it had been banned, as art has always been easily sold when banned.”

Depending on the night and the viewer, a Cinema Guild showing might provide cheap, date-night entertainment, improve language skills, or provoke emotional catharsis. Hubert “Hugh” Cohen, who joined Cinema Guild in 1960 as a grad student, recalled a screening of Children of Paradise where noted British actress Rosemary Harris, on a night off from performing in Ann Arbor, exited the film “sobbing.” At other times, patrons needed help to get in the mood: “Now and then during a Chaplin film, there would be no sound coming out of the auditorium and I’d go in, just puzzled. ‘How could it be, with these hilarious films?’” he recalled. Down the hall was a sculpture studio. “There was this sculptor with this deep voice, and I used to go and get him and plant him in the middle of the theater. Get him laughing, to warm up the audience.”

Cinema Guild’s expanded programming made the Gothic Film Society increasingly irrelevant, and with its subscribers dwindling, the rival organization shut down in early 1963.

Though Cinema Guild continued to share much of its proceeds with other student groups, this policy was fading as well. “It fell off pretty quickly,” Hugh Cohen recalled. “Because film was becoming so important, we didn’t have time to cater to anybody else’s tastes. And we were making it on our own.”

During the early 1960s, Cinema Guild’s programming grew more and more adventurous. Full evenings were now devoted to programs of experimental films, while special series highlighted individual directors, actors, and countries.

Rick Ayers fell in love with the French New Wave as a high school student in the Chicago suburbs, watching films like François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player at a ramshackle downtown revival house. Ayers’ family had strong cultural and political interests, and after starting at the university in the fall of 1965, he joined both Cinema Guild and Students for a Democratic Society. (His older brother Bill would become a leader in the SDS and its violent offshoot, the Weather Underground.) “It was all kind of artsy, outsider people,” Ayers recalled of Cinema Guild. “Critical people. And there was a certain amount of gay students in there who I didn’t even understand that that’s what the deal was. We didn’t have language for that.”

They took programming seriously: “We would read this French journal, Cahiers du Cinéma,” Ayers recalled. “They were obsessed with John Ford, so we would show John Ford or Howard Hawks and stuff like that.”

The group also presented the latest work of foreign directors like Ingmar Bergman, Michelangelo Antonioni, François Truffaut, and Jean-Luc Godard, then at their creative peaks, and whose films the Campus Theatre didn’t always book. Ayers recalled: “It was a radical idea to consider that someone’s serious aesthetic interest should be movies and should be movies that weren’t American. I think the way we saw ourselves was completely critical of the canon, such as it was.” Since the university wouldn’t offer its first film studies classes until 1968, Cinema Guild’s programming effectively became a film school that was taken advantage of by future notables like Ken Burns and Lawrence Kasdan.

Though Cinema Guild’s student members brought energy and fresh perspectives, the glue that held it together was Hugh Cohen and Ed Weber. Both joined in grad school and remained involved after taking jobs with the university, Weber curating the Joseph A. Labadie Collection of social protest materials, and Cohen teaching English and then film. “They were the continuity,” Ayers remembered. “But they were very, very attentive to what we wanted to do. I was really on a learning curve about this kind of film, so I would certainly defer to both for their knowledge. But I never felt like they were bossing us around.”

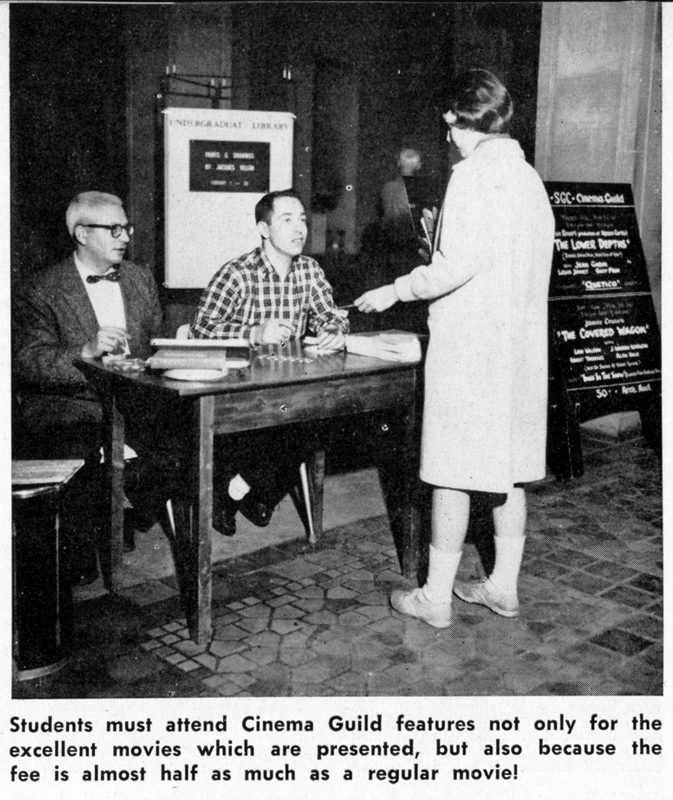

A student buys tickets from Ed Weber (left) and Hugh Cohen. | Michiganensian Yearbook

Cohen and Weber would carry on as mentors to student board members for nearly four decades as Cinema Guild evolved into a campus institution. It was a founding cosponsor of the Ann Arbor Film Festival, and challenged U-M administrators with controversies like the screening of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures.

The 1967 bust of the group’s board members made the New York Times and split campus into pro- and anti-censorship factions. The administration refused to help, but Cinema Guild raised funds for their defense with events like a Hill Auditorium performance by Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground.

The case came to trial in December, only to end abruptly when one of the students agreed to plead guilty to a lesser charge. Afterward, the group was more cautious, at least for a time. “We were a lot more self-censoring than we had been before,” remembered Cohen, one of those arrested. “Not wildly, because that was the turning point of the whole culture, so everything was changing.”

On happier occasions, Cinema Guild helped bring to campus luminaries like Frank Capra, Elsa Lanchester, and maverick director Sam Fuller, among others. It also counted as members future director-screenwriters Lawrence Kasdan and Richard Glatzer, Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor John Nelson, Oscar-nominated film editor Jay Cassidy, film critic/author Neal Gabler, script supervisor Mary Cybulski, and her husband, editor John Tintori.

Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground played a fundraiser after an obscenity bust. | The Michigan Daily

[drocap]C[/dropcap]inema Guild was not alone. By the late 1970s, more than a half-dozen sometimes contentious groups programmed films up to seven nights per week, year-round. These included Cinema II, whose eclectic offerings ranged from classic Hollywood to the French New Wave; the Ann Arbor Film Cooperative, screening more controversial, cutting-edge fare; Mediatrics, a university-underwritten group that focused on recent mainstream titles; and Alternative Action, which shared its profits with activist organizations like PIRGIM and the Ann Arbor Tenants Union.

At the start of each semester the groups distributed calendars—Cinema Guild alone printed 15,000. Taped to dormitory walls and off-campus refrigerators, they testified that their owners were cool and in the know.

The campus film societies reached their peak in the 1980s, bringing in as many as 500 movies per semester. But their finances were shaky—in 1977 alone, they collectively lost $15,000—and the growth of cable television and home video proved their undoing.

Despite the university’s belated offer to subsidize auditorium rentals, by 1990 Cinema II and Alternative Action had folded and Cinema Guild and the Film Coop were each down to operating just a couple of nights per week. As attendance continued to plunge, in 1991 Coop member Matt Madden lamented to the Daily, “Up until the last five years or so, it wasn’t really an issue, since everyone knew who the film societies were. Now, all of a sudden, we find our audience totally gone, and we’re unknowns.”

Even VIP guests like Bobcat Goldthwait and Bruce Campbell couldn’t turn the tide, and the Coop was dissolved in 1997. Cinema Guild struggled on for another decade, the last half of which largely consisted of occasional video screenings in a basement classroom, until its unheralded final show in August 2007. Today only the university-subsidized M-Flicks (the former Mediatrics) remains, screening a half-dozen films per semester.

Cinema Ann Arbor is available from local bookstores and as an e-book from the Ann Arbor District Library. It was named a 2024 Michigan Notable Book by the Library of Michigan.