Food Gatherers held a series of food distributions in response to uncertainty about federal food benefits. In the first three events, they gave food to more than 600 households. | J. Adrian Wylie

On a chilly mid-November Wednesday morning, volunteers from Food Gatherers assembled in a parking lot at Briarwood Mall, outside JCPenney. It was the second in a series of four hastily announced food distributions following a freeze in federal food benefits.

Three rows of cars were already waiting, the line creeping back to the Briarwood Mall service drive, so Food Gatherers kicked off the event thirty minutes early. After checking in at tents reminiscent of those used by tailgaters at the Big House, each motorist received a box with forty-two pounds of food, including oatmeal, shelf-stable milk, canned chicken, a sack of potatoes, and squash.

The first three events distributed food to more than 600 households, says Food Gatherers CEO Elaine Spring.

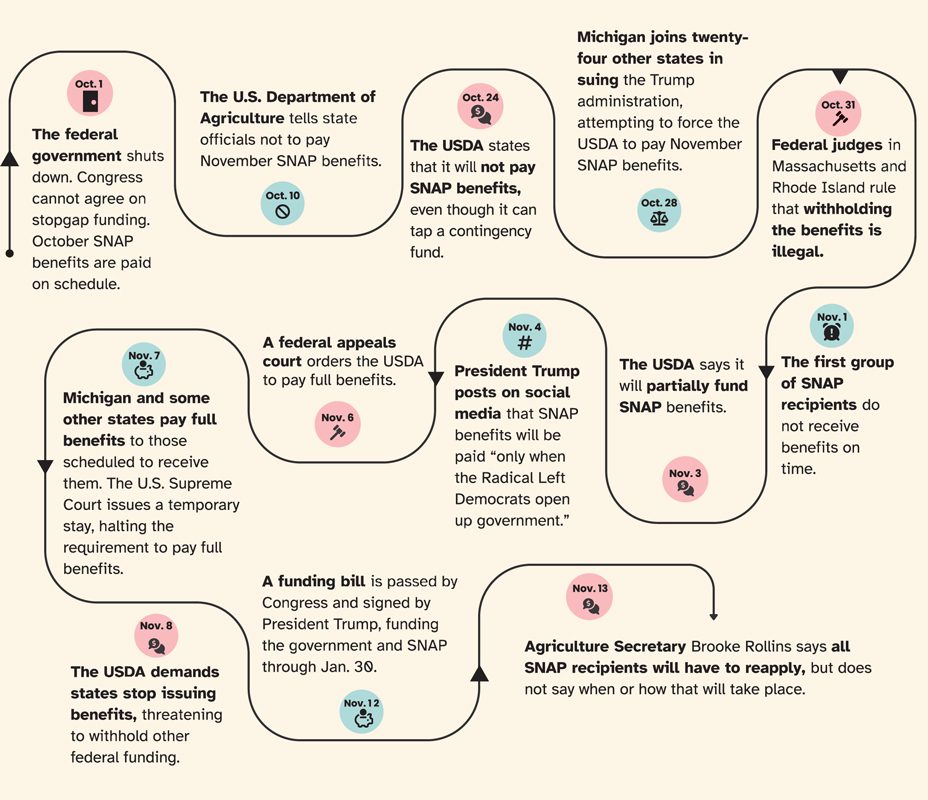

The distributions came amid continued confusion over the status of SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), the federally funded system once known as food stamps. Beginning in late October, a series of court cases delayed, released, and again delayed deposits to SNAP recipients.

By the time the Observer went to press, benefits were restored. But the crisis acutely illustrated the level of need that exists across the community.

Nationally, 42 million Americans receive SNAP benefits, or about one in eight people. Michigan has approximately 1.4 million SNAP recipients—roughly 13 percent of the state’s population—and according to 2024 Census data, 13,541 Washtenaw County households receive these benefits.

The MI Bridges program reviews the expenses, assets, and income of family members to determine eligibility. In 2024, the average monthly benefit in Michigan for a household was $335.05, or $173 per person, although some recipients get more and others much less.

Payments are made by electronic transfer and can be tracked on an app. Recipients can use the funds to purchase groceries—fruits and vegetables, meat, dairy and fish, cereal and snacks—but not alcoholic beverages, marijuana products, hot food, or cleaning supplies.

Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill, signed into law on July 4, scheduled cuts to SNAP valued at $186 billion through the end of the decade. Currently, the federal government funds the entire program; by 2030, states will be expected to shoulder some of the expense. They will also have to pay three-quarters of the program’s administrative costs, up from 50 percent.

But the complete halt to benefits during the congressional standoff caught Spring and others off guard. During the previous federal shutdown in 2018, SNAP continued without interruption.

“We did not anticipate a SNAP pause during the shutdown because there’s never been a pause in SNAP,” says Spring.

Related

Hunger Grows: Local food pantries are juggling record numbers of urgent requests for assistance.

Colton Ray, a graduate student at EMU, kept checking the app in early November. His $290 monthly payment typically loaded on the fifth, but it didn’t show up as scheduled.

Fortunately, his money showed up on November 7, in the initial wave of deposits made by the state amid the legal tangles. But Ray was already coming up with options if the funds didn’t arrive.

Last summer, he found a chest freezer that someone gave away and began stockpiling frozen meals. Ray, who works at EMU’s Swoops Food Pantry, planned to shop there for more groceries, and assembled a list of area locations where he could get deals on food. “I can find the right coupon or go on the right day,” he says.

The SNAP delays came as a number of residents were already feeling the pinch of the government shutdown and steps taken by the Trump administration to cut assistance programs.

Last spring, President Trump ordered more than $1 billion in cuts by the USDA: $420 million was cut from Local Food Purchase Assistance, which enables funding for states to purchase goods from farmers and distribute them to food charities, and $660 million from Local Food For Schools, which gives schools money to buy locally sourced food for student meals. Aid provided through the Emergency Food Assistance Program, which purchases food and provides it to states to share with food banks, was either frozen or cut.

Meanwhile, some federal workers, such as those at the National Vehicle and Fuel Emissions Laboratory on Plymouth Rd., were dismissed earlier in the year. The shutdown furloughed others, while still others were expected to work without their scheduled pay, including employees at the Federal Correctional Institution in Milan.

Like other area food charities, Aid in Milan saw a jump in the number of people seeking help. Six years ago, before the pandemic, the food pantry typically served 125 households a month, says executive director Andrew Felder. In October, it fed 610. “October broke every record we had, and that was before the pausing of SNAP benefits,” Felder says.

In the last week of October and the first week of November, Food Gatherers’ website had 9,000 views, compared with 2,000 in the previous two weeks, prompting the site to crash briefly.

By early November, the average number of shoppers at Swoops Food Pantry rose to a hundred a day, compared with ninety-two in October. In the two-week period between October 27 and November 10, some 10 percent of new shoppers were on SNAP—up from 7.4 percent over the previous three months. And, with about 13 percent identifying as vegetarian or vegan, says Ray, Swoops was having trouble keeping tofu and alternative milks in stock.

Blue LLama sous chef Shani Patterson aims to offer Community Family Meals to those in need through the end of the year. | J. Adrian Wylie

Across Ann Arbor and around Washtenaw County, restaurants, businesses, and residents reached out to help the hungry. Detroit Filling Station, Palm Palace, Argus Farm Stop, Mama Pizza & Curry House, and Issa’s Pizza were among those offering aid.

Blue LLama on Main St. is usually closed on Monday and Tuesday, but kitchen staff came in to make sixty meal boxes with black beans, rice, and collard greens. The meals were distributed during the lunch hour on Veterans Day to anyone who asked, while others were handed out at the Blake Transit Center a block away.

Blue LLama sous chef Shani Patterson, who was in New York City during the pandemic, came up with the idea after seeing restaurants feed first responders and hospital staff. Rather than ask patrons to show their SNAP identification, she decided to make it free to all.

“In Ann Arbor, which is an affluent area, you never know who needs it,” Patterson said. The response to the meals “shows me that gap between us and food insolvency.”

Patterson hopes to continue offering the food boxes—which she calls Community Family Meals, same as the Blue LLama employee shift meal—through the rest of the year.

In Saline, Mancino’s Pizza & Grinders provided a free extra-large pizza to SNAP recipients, and gave away a total of 103 pies. “I just felt compelled to help,” says owner Kevin Lawson. “I couldn’t sleep at night knowing people were going to bed hungry.” Customers phoned him to donate pizzas, including one who paid for ten pizzas and told him he now had a customer for life, Lawson says.

Meanwhile, Growing Hope partnered with the Ypsilanti Farmers Market to offer the Ypsi SNAP Gap, providing $40 in food tokens for SNAP recipients and anyone food-insecure to use at the market each week. The tokens, available through March, can be exchanged for any market food item, including the hot meals and prepared foods that SNAP normally does not cover. The Ann Arbor Farmers Market lifted the $20 match limit for Double Up Food Bucks, which gives SNAP recipients two-for-one deals on fruit and vegetable purchases, and offered an unlimited match until December 31.

Community members have also donated money. The giving circle Ann Arbor Women for Good voted to give this quarter’s donations to Food Gatherers; so far, they’ve raised $6,300 of their $8,000 goal. And students at Community High School, who stage an annual fundraiser to support Food Gatherers, set a $100,000 goal for this year’s drive (last year they raised a record $97,000). By press time, the Community High Fights Hunger drive topped $82,000.

But these efforts can’t completely offset the impact the SNAP has on the area.

“SNAP is not replaceable,” says Markell Lewis Miller, Food Gatherers’ director of community food programs. “We can do our best to mitigate the impact of SNAP in a month but it’s logistically and economically not possible to replace it.”

Even while searching for solutions to the SNAP situation, lessons were emerging.

Lesson One: even seemingly financially secure households may be only a paycheck or two away from needing aid. Officials at multiple food charities say the food crisis drew in people their organizations had never seen before.

“You have people who grew up their entire lives without needing to rely on a pantry,” Aid in Milan’s Felder said. Among federal employees, “there is a whole group of people who have considered themselves to be relatively middle class. Their minds don’t go to receiving aid. They go to making a donation.”

Lesson Two: Ann Arborites are eager to help. “We live in a community that’s incredibly supportive and responsive,” Miller says.

While she’s impressed with how quickly the food drives emerged, she also stresses that in an unexpected crisis, money helps the most. “Cash gives us the flexiblity,” Miller says, saving precious time for volunteers and staff.

“We can take a dollar you would spend at the grocery store and stretch it much farther,” adds Felder. But he doesn’t discourage anyone from contributing goods. “If that’s what feeds their soul, that’s what I want them to do.”

And Lesson Three: Even though SNAP benefits ultimately came through, there’s still an atmosphere of preparedness—even caution—moving forward.

“We still don’t know what December will look like,” says Colton Ray. “So, I have to be very intentional about stretching the benefits.”