“Macular degeneration was a terrible diagnosis for a librarian, writer, reader, publisher, historian, and art lover,” says Ed Wall. He was fifty-five years old when he was diagnosed; twenty-two years later, he is legally blind. His Pittsfield Township home office is full of great works of art that he can appreciate only in his memory.

Blindness was especially devastating, he says, because “I learn, remember, think, and write visually. I can’t absorb what I hear. In college, I wrote reams of notes, then took them back to my room, reread them, and finally understood what the professor was saying.”

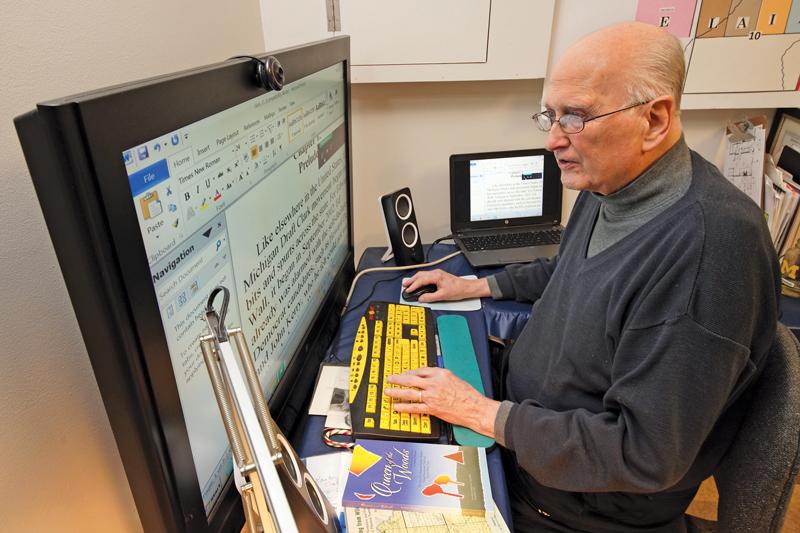

For six years, Wall struggled with depression and frustration–until a longtime friend, Ford engineer John Whitaker, offered to help him find adaptive technologies that could help compensate for his vision loss. Initially, they tried screen readers with an interface based on speech. That failed, so they bought a forty-two-inch television that they combined with a screen-magnifying program and a low-vision keyboard with black and yellow keys to heighten visual contrast.

Whitaker glued rubber dots on some keys so Wall could position his hands accurately, and he found an inexpensive screen-reading program that allowed Wall to highlight text. He listens and relistens to the text until he can visualize it.

Thanks to this technology, Wall began to write again. Now he works on projects that would daunt someone with 20-20 vision, starting with histories close to home. In the past decade, he’s written five books on Pittsfield’s history and has an even longer list of books he wants to write.

“Because I can’t see, I have to memorize all the content before I can write a chapter, so the process has to be completely immersive–and it can’t be rushed,” he says. Peering into a magnifying glass that is trained on the giant computer screen, he studies original materials, maps, tables, analyses, and surveys.

His wife, Mary Ellen, helps track down genealogical facts and transcribes township survey notes, patent records, and personal correspondence. She also describes the locations and relationships on maps and repeats the descriptions until Wall can visualize them.

He then synthesizes the information and composes and memorizes his text before typing it. “When one chapter is completed, I literally clear out my research memory before I start the next chapter.”

—

In his early thirties, Wall served on the Pittsfield Township board. “Old-timers attended board meetings for entertainment, and, as issues were being discussed, they often interjected stories about places, people, and historical context,” he says. He spent hours after meetings talking with them. Years later, he realized that if he didn’t attempt to capture some of their accounts, they would be lost forever.

His mission is to preserve the memories and fading records of the first community in Washtenaw County to establish a school, cemetery, and church. According to Wall’s Emerging from Wilderness: Formation and First Settlement of Pittsfield Township, Michigan, the township took shape in June 1824, when pioneers from upstate New York visited the Michigan Territory General Land Office in Detroit to purchase farmland for $1.25 an acre.

“In four days, the land on all four corners of Packard and Platt was purchased, forming the nucleus of the future Malletts Creek community,” Wall says. Malletts Creek and an Indian trail (now Washtenaw Ave.) crossed the properties bought by Ezra and Charles Maynard, Lewis Barr, Claudius Britton Jr., and Luke Whitmore. Ezra and Charles Maynard were the original owners of what today is Cobblestone Farm.

In the summer of 1825, Luke Whitmore donated land for the first school and church on a corner of his farm (facing what is now Packard Rd., one-quarter mile east of Platt). Under the canopy of a huge oak tree, Elzada Fairbrother taught sixteen students sitting on logs, and on Sundays the community gathered there for religious services. By the end of the summer, the pioneers had constructed the Malletts Creek Schoolhouse with logs from Whitmore’s farm. “This was the first school in Washtenaw County,” Wall says.

—

His self-appointed role as Pittsfield’s historian is the latest turn on a winding career path. Wall was born into a Quaker family in Cherokee, Iowa, and met his future wife, Mary Ellen, at Olney Friends School in southern Ohio. Then they headed to the University of Iowa. “I was not a serious student in high school,” he says–he was more interested in racing hot rods–“but I challenged myself to do better in college.”

By taking twenty-six credit hours each term, in four years he earned a triple major in history, political science, and Chinese language and civilization. Married at twenty, the Walls moved to Ann Arbor in 1963, so Ed could work on a master’s in Chinese military history (1965) and a master’s in library science (1966) as a Ford Foundation Scholar. After graduation, he joined the staff of the U-M Dearborn library as reference librarian. Within a year, he was head librarian, and in six years he expanded the library’s collection from 50,000 to 120,000 volumes. Meanwhile, they had four children and now boast of twelve grandchildren. “Our family is our greatest accomplishment,” he says.

Wall planned the U-M Dearborn’s Mardigian Library, arranging it so that the first floor could later be converted into an art museum. And in 1968, the Walls opened Pierian Press, based in a house on Golfside Rd. not far from their own home. They published reference materials whose titles ranged from Poole’s Index to Periodical Literature, 1802-1881 to A Matter of Fact: Statements Containing Statistics on Current Social, Economic, and Political Issues and reference books on contemporary culture (including the Beatles, Elvis Presley, and the Andy Griffith Show). Wall also founded and edited three library-related journals.

Meanwhile, the Walls became prodigious art collectors. “We were conventional at first, investing in works by established artists, such as Picasso, Matisse, Dubuffet, and Miro, but we soon began collecting works by lesser-known artists,” Wall says. “We supported a number of emerging artists, acquiring their work and writing their exhibition catalogs. Most of the artwork in our collection is associated with special friendships.”

Three of those friends now have museums dedicated to their work. One is internationally renowned painter Arthur Secunda, who has roots in Michigan. The Walls met him in Detroit in 1971 and went on to acquire 2,000 of his works. They have donated more than 500 of those to museums across the U.S. and Europe, including the U-M Museum of Art. In 2012, 500 other Secunda works from their collection served as the basis of the Arthur Secunda Museum at Cleary University in Howell.

—

Wall lists seven careers–to date: “My family, library administration, publishing, local government, running regional political campaigns, championing studio glass, and promoting Arthur Secunda’s body of work.” He has written a memoir of his childhood, Turning Pages, and two novels for his grandchildren. These, as well as Emerging from Wilderness, were published under his Pierian Press aegis. The manuscripts for the other Pittsfield histories are waiting for his favorite book designer to find time in her schedule. Among future writing projects are books based on his enormous art collection.

Wall serves on the township’s Arts & Culture Excellence Committee and keeps tabs on the Cleary museum. At one time he also raised old and rare tulips, some dating to 1585, but he couldn’t find adaptive technologies to help him care for them, so he was forced to abandon that hobby.

“All of us have obstacles in life. I have not been able to overcome them all, but that makes me appreciate all the more those that I have.”

Hello – this is not a comment but rather I am interested in speaking with Mr. Wall. My family owned a farm at the corner of Platt and Ellsworth for many years. It is now Lillie Park. I’m starting to research the history and am interested in any additional information. The farm meant a lot to my family, my dad in particular. But his dad (Richard Gearhart) apparently sold it to the Township for a dollar after a snowmobiler was decapitated by a barb-wire fence on the property (that’s the story I was told anyway). I don’t know what year that was… probably the late 1990’s? It was a working farm for a long time. Roy and Mabel Gearhart, my great-grandparents owned it, Mabel worked with 4-H groups and boarded students from U of M in trade for helping her work the farm after Roy passed. Art and Mary (I don’t know there last names) former students then lived there once she passed. Thanks, Kristine