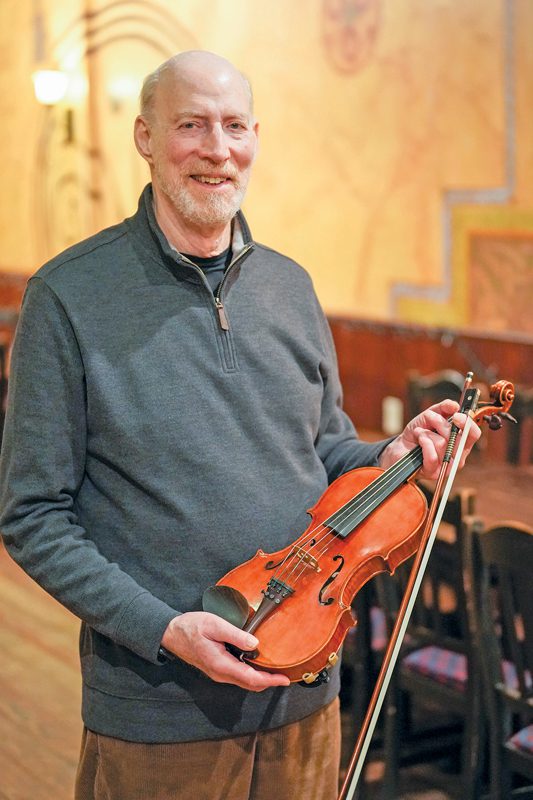

Photo by J. Adrian Wylie

On Sunday nights, Conor O’Neill’s Irish Pub reverberates with the sounds of guitars, flutes, fiddles, bodhráns, harps, accordions, harmonicas, whistles, bouzoukis, and uilleann pipes. Often, the toe-tapping, soul-searching tunes are led by Marty Somberg on the Irish fiddle. “At first I seem like an unusual choice,” he admits, “since my heritage is Polish and Jewish!”

By day Somberg runs his own graphic design firm. On nights and weekends he paints, performs, and practices. “The arts occupy my mind almost completely,” he says, “and they always have.”

One of his earliest memories is of pedaling his tricycle to a corner drugstore in 1950. He was only three, but when he studied the enticing rack of candy bars just inside the door, he was “dazzled” by the vivid orange/blue wrappers of the Clark bars. “I happily rode home, clutching my prize,” he recalls.

“My mother caught me eating the candy and immediately escorted me back to the drugstore” to pay for it. “But from that moment, at that very early age, I have always been intrigued by colors.”

Tall, lanky, and balding, with a bristly, short, silvery beard, Somberg has spent his life jockeying between the visual arts and music. He spent his early adult years playing in rock and folk bands before his passion fixed on the Irish fiddle in his twenties. “Fiddles can tell so many tales,” he says. “They evoke so many emotions.”

Somberg comes from a long line of storytellers. “Actually, our name used to be Wortman [meaning writer or wordsmith]. But when one of my father’s ancestors was about to be conscripted into the Russian army, he changed his name and our future.

“He was one of several sons, but in those days, a man couldn’t be conscripted if he was an only son. So, my ancestor arranged to be adopted by a childless couple whose name was Somberg. We’ve been Sombergs ever since.”

Sometime around 1920, his Somberg grandparents emigrated to Detroit. His father, a housepainter and later a scrap metal dealer, loved to sing; he occasionally was asked to substitute for their synagogue’s cantor, while Marty and his brother Lenny sang in the choir.

When Marty was eight, his piano teacher “found out I was faking an ability to read music” and taught him chords. At ten, he met a boy at summer camp who played the ukulele. When he arrived home, he woke his father from a nap and asked him to immediately take him to a music store to buy one, promising to share it with Lenny.

“I’m left-handed and Lenny was right-handed, so we flipped a coin to decide which way to play the ukulele,” he says. “I lost, which turned out to be a good thing, since it’s tough to play instruments left-handed.”

He also “drew from a very young age, and I was fascinated by design—clothing designs, architectural designs, furniture designs.” But music took priority when he discovered that he could reproduce his favorite pop songs after hearing them on the radio. He began imitating the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, and Elvis to entertain friends and family. Later, his repertoire expanded to the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, Cream, Eric Clapton, and Jimi Hendrix—“my all-time favorite rock musician.”

When he entered high school, Somberg joined his brother’s vocal group, the Highlighters. “We sang commercial folk music, some in Hebrew, in the Kingston Trio style—we even wore matching striped shirts,” he recalls, grinning. They played at hootenannies and won a local music competition, “which boosted our egos.” But the Highlighters disbanded when its older members went off to college.

The brothers bought guitars and formed a psychedelic rock group called the Southbound Freeway. They began drawing local attention, playing at the Michigan State Fair, opening for the Lovin’ Spoonful, and recorded a single, “Psychedelic Used Car Lot Blues.”

“We even had a fan club and, amazingly, a few groupies,” Somberg says. The life of a rock musician looked very promising.

The band moved to Los Angeles with high hopes, but soon dissolved. The Sombergs then formed an indie-folk group, Camp Hilltop, playing original songs interspersed with 1950s hits. Marty designed their concert posters.

We “got by pretty well for a while,” he says, opening for Neil Young, Arlo Guthrie, Tiny Tim, Ricky Nelson, the Clara Ward Gospel Singers, and Judy Collins. “We got to within one or two degrees of separation [of stardom], but our form of music was just not quite right at the right time. That was the point when we realized we had to move on.”

He enrolled in art classes at Laney College while continuing to perform in a succession of bands playing oldies, pop, and bluegrass. And he discovered his passion when he borrowed a bandmate’s fiddle.

“Celtic music covers a broad geography in Northern Europe,” he explains. “Each national tradition has its own particular flavors, feel, and tones. The scales and modes evoke different feelings. And the Irish form has a strain of melancholy that resonates with who I am.”

Eventually he dropped out of college and headed for Ireland, staying “until I ran out of money—about the time I realized how cold Irish winters could be.”

He went back to California, where he played guitar and fiddle with a succession of bands. He headed east with an Irish trio that produced an album, but they split before it was released. He then joined Celtic Thunder’s stage show. “I made a better living playing with them than any other band I belonged to.”

Eventually, however, he needed to move on. “My parents were getting older, and I’d been a college sophomore for eleven years. I had other things I wanted to explore.”

Returning to Michigan in 1982, he enrolled in EMU’s graphic design program and worked a series of corporate and agency jobs before launching his own company, Somberg Design. In the early 2000s, he completed an MFA and added teaching to his resume while keeping his fiddle close and performing regionally.

During that time, he married a fellow artist and talented illustrator. His wife Maggie occasionally assists on brochures and book illustrations.

Somberg continues to design publications, paint, play the fiddle and guitar, and take violin lessons—“trying to catch up on technique after starting so late,” he says.

“I have no regrets about my circuitous path—it certainly wasn’t conventional, but I’ve been able to follow my passions or muse or whatever you might call it.

“I wouldn’t call myself ambitious, just dedicated. I did—and continue to do—what I love doing.”