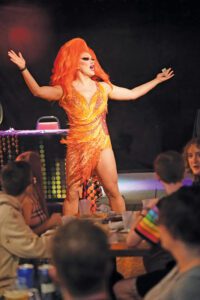

Jadein Black is working on the logistics for an upcoming fundraiser for Ann Arbor Pride while her partner drives her to a gig in Grand Rapids. When a reporter calls, she closes her laptop and launches into an unscheduled interview. Multitasking is a necessity for the thirty-two-year-old performer and educator, whose drag troupe Boylesque Michigan is booked at as many as eight shows a week.

Photo: J. Adrian Wylie

“I’m coming up on fifteen years of drag in the fall,” Black says. “I got to a point, probably in my tenth year, where I got bored performing in nightclubs. I wanted to make a difference in our community and provide them with more resources.” In addition to hosting city-sponsored events like Ann Arbor Pride and the Ypsilanti Bicentennial, she performs at private venues such as Blue LLama, Avalon, Conor O’Neill’s, and her longstanding Drag Musical Bingo show at the Tap Room in Ypsilanti. This month she’ll make her tenth appearance as host of Ann Arbor’s Pride celebration (see Events, Aug. 5).

Most of her shows are fundraisers. “My main goal is to spread positivity, bring community together, and raise awareness not only for the nonprofit that we’re raising money for but for myself,” she says, “because drag in the United States and across the world has been victimized.”

The American Civil Liberties Union is tracking close to 500 anti-LGBTQ+ bills across the country, some of which would prevent minors from attending drag shows—or ban them outright. Black no longer performs in Florida, where she has a significant following. “It hurts my heart that in these states it’s illegal for kids to go out and see a drag performer on the street at Pride,” she laments. “There are other places that might be less appropriate for kids, where people wear a lot less clothing, and it’s not illegal.”

“The unknown is scary,” says Meghan Miller, a bartender at the Tap Room. “There are a lot of people I’ve personally seen who have never been to a drag show, who may have had misconceptions about it, come in and been comfortable, and come back.”

Miller frequently brings her seven-year-old daughter to Drag Bingo and says she loves the music, costumes, and big hair. “We have an all-ages, child-friendly show,” Miller explains. “I think probably at the end of the day Jadein’s biggest message is that our children should grow up in a world with less hate in it. You can turn on the TV and see messages that are wildly inappropriate for a child any given second. So there’s a double standard there that I don’t understand.”

Though efforts to restrict drag performances in Michigan have failed, members of the Proud Boys heckled Black twice last year, during Drag Queen Story Time at the library and at the Ann Arbor Summer Festival. One heckler brought his young daughters, who held up signs accusing Black of sexualizing children. A large number of families were in the audience. “As a teacher you’re always thinking about what your next move is. I had to set an example for those kids,” Black says.

At a June city council meeting, mayor Christopher Taylor announced that both the city and Washtenaw County had proclaimed June as Pride month. He highlighted the city’s history of LBGTQ+ milestones, from electing some of the first gay officeholders to recently banning the discredited practice of conversion therapy. And he honored several activists in the community, including Black. When she accepted the honor, she thanked the Ann Arbor police for protecting her during the Summer Festival incident.

—

When not in drag, Jadein Black is Paul Bowling, a gay man who has a degree in music education from EMU, teaches in the Ypsilanti public schools, and is the vocal director for musicals at Lincoln High School, where Bowling was once a gay youth himself.

It was difficult, but “drama and choir was my safe space,” Black recalls, adding that the school has “come a long way” since then. Teaching music and theater are her way of offering a safe space to others. “Performing arts is so important for young people, because it enriches minds and lets positive energy flourish.”

Black learned to embrace her identity in the face of controversy early in life, coming out as gay at thirteen, a year after her father died. “If I came out to my father I don’t think he would have supported me. This is something that I struggle with every day.”

Black’s mother was always supportive. She introduced her son to a gay couple who were clients of her house-cleaning side business. Meeting them was an epiphany. “You can grow up and have a nice house, you can grow up and live happily and love whoever you want? This is amazing, this is exactly what I want for my life,” she recalls thinking.

A video posted to Black’s YouTube channel shows her at nineteen, preparing for a drag performance. While doing her hair and makeup, she talks about her family. “The most negativity that I’ve had is from my grandparents—they’re very religious.” But the family rift eventually healed. “My grandparents now are okay with it,” she says in the video, applying eyeliner. “They respect what I do.”

Her gender-fluid life partner performs in Boylesque as Austin Black.

During the pandemic, when school plays were suspended, the troupe posted 184 virtual lessons for children on topics ranging from cooking and dance to music and literature.

“We had millions of positive responses from viewers,” Black says, inspiring her to begin offering in-person family-friendly Drag Queen Story Time events.

—

Black keeps finding new ways to celebrate diversity, both in and out of drag. “The most fulfilling thing for me is to meet people through networking who have the same vision that I have to make the world a better place,” she says. “You might see me run for the Ypsi school board someday.”

Even the Proud Boys’ disruption of her performance at last year’s Ann Arbor Summer Festival turned into a positive moment for Black and her supporters.

“All the parents got up and stood around us,” she recalls. “They were in solidarity with me. If I show them ‘Don’t let hate win,’ I think that is where we all win in the end.”