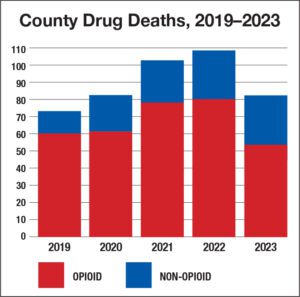

EMS responded to 521 overdoses in 2023, up from 458 the year before. Yet deaths were down, from a record 109 people in 2022 to eighty-two last year.

Nicole Adelman of the Community Mental Health Partnership of Southeast Michigan with a Narcan (naloxone) vending machine at the Washtenaw County Courthouse. “The amount of naloxone that we’ve distributed over the past couple years is amazing,” she says. | Photo: Mark Bialek

Once rare in Washtenaw County, overdoses started to rise in the 1990s and 2000s, when overuse of prescription painkillers created a new generation of opioid addiction. According to prosecutors, a single clinic on Golfside Rd. dispensed 1.5 million doses of narcotics before it was raided in 2015. After legal sources were cut back, many users turned to heroin and other street drugs—and when dealers began mixing those with fentanyl, deaths skyrocketed. According to a graph created by the Washtenaw County Health Department, the potent synthetic was implicated in 86 percent of 2022’s opioid deaths.

Judging from the number of overdoses, the drugs sold locally are as dangerous as ever. What changed is much wider access to Narcan, a nasal spray that can temporarily reverse an opioid overdose if it’s administered in time.

Originally a prescription drug carried by EMS crews and other first responders, Narcan was approved for over-the-counter distribution last year. It’s now widely available to users and their friends and families. “We know that there are many people that overdose and survive,” says county health officer Jimena Loveluck. “And many times, that survival is [because] someone around them has administered Narcan.”

“We have seen an increase in availability of harm-reduction resources in our communities such as Narcan,” agrees county epidemiologist Kaitlin Schwarz. It’s sold at pharmacies, distributed free by community organizations, and “we’ve seen an increase in the number of locations in our county that are putting in Narcan vending machines.”

“The amount of naloxone that we’ve distributed over the past couple years is amazing,” confirms Nicole Adelman, substance use services director at the Community Mental Health Partnership of Southeast Michigan. The group distributes most of its funds to community mental health units in Washtenaw, Livingston, Lenawee, and Monroe counties. But here, it also directly oversees “contracts with the substance-use treatment providers, prevention providers, recovery—the whole spectrum of care,” Adelman says. “We focus on all substances, but we do have certain funding that focuses specifically on opioids.”

That includes paying for Narcan. The Washtenaw County Health Department alone distributed 2,237 two-dose kits in fiscal 2023, up from 578 the previous fiscal year. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services distributed another 22,872 directly to local providers, up from 10,092.

In February, the health department joined neighboring counties to relaunch “It Is Possible,” a multimedia campaign that “highlights stories of local people in recovery to foster hope that recovery from substance use disorder is possible,” according to a press release. It also offers safety tips, including using fentanyl test strips (available online at bit.ly/fentteststrip).

The county’s addiction-prevention and harm-reduction efforts will soon have more funding. According to the the Michigan Association of Counties, “In 2021, a $26 billion nationwide settlement was reached to resolve all Opioids litigation brought by states and local political subdivisions against the three largest pharmaceutical distributors” for their sales of narcotic painkillers.

Counties, townships, and cities are slated to receive nearly $725 million over the next eighteen years. Loveluck says that Washtenaw’s share will be about $450,000 annually. She doesn’t “have specifics yet about how those resources will be deployed,” but says two priorities will be medication-assisted addiction treatment and making Narcan available.

Some critics are concerned that the availability of Narcan will create a “moral hazard”—encouraging users to take more risks because they think they have protection. But according to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Studies have shown that naloxone access and distribution does not lead to more drug use or riskier drug use.”

While the downward trend in deaths looks “really promising,” Schwarz cautions, the county is seeing “more overdoses involving multiple substances and more non-opioid-related overdoses.” While the opioid deaths fell sharply last year, from eighty to fifty-four, the number of people killed by other drugs scarcely changed: There were twenty-nine in 2022 and twenty-eight last year.

“We do see a lot of cocaine” in overdoses, Schwarz says. “We’re seeing the impacts of alcohol use as well as methamphetamine.” It’s being called the “fourth wave” of the opioid crisis: people knowingly or unknowingly using multiple drugs at the same time.

Cocaine and methamphetamine are stimulants, not opioids—but lately, the street versions often also contain fentanyl. According to the county graph, in 2022, 63 percent of opioid deaths involved stimulants.

—

This article, graph, and photo caption have been edited since they were published in the March 2024 Ann Arbor Observer. The errors noted below have been corrected:

—

Calls & letters, April 2024

Multiple opioid corrections

Our March article on opioid overdoses (“Drug Deaths Down,” Inside Ann Arbor) included incomplete and misdated figures for the availability of the opioid antagonist Narcan (naloxone). Kits distributed locally more than doubled from fiscal 2022 to fiscal 2023, both through the state portal (from 10,092 to 22,872) and through the Washtenaw County Health Department (from 578 to 2,237). Our article cited lower partial-year figures and attributed them to the wrong fiscal years.

We also did a double disservice to Nicole Adelman, substance use services director at the Community Mental Health Partnership of Southeast Michigan: we got her title wrong in the article, and a photo caption placed her in the wrong location: the photo was taken at the Washtenaw County Courthouse, not the Malletts Creek library.

Reader Craig Harvey also caught an error in the accompanying graph: “According to the text, opioid deaths were 54 [in 2023], while the graph shows about 44,” he wrote. “And according to the text, non-opioid deaths were 28, while the graph shows about 38.”

The text was correct: last year’s drop in deaths was almost entirely due to more people surviving opioid overdoses–largely thanks to the greater availability of naloxone.