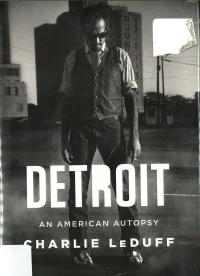

‘I reached down the pants cuff with the eraser end of my pencil and poked it. Frozen solid. But definitely human.” And so Charlie LeDuff begins Detroit: An American Autopsy, non-fiction that often reads like a noir thriller.

LeDuff, then a Detroit News reporter, was called to the abandoned building to witness a gruesome sight: a corpse at the bottom of an elevator shaft, encased in ice —”his legs sticking out like Popsicle sticks.” The story becomes a media sensation but in this dysfunctional city, a day passes before anything is done with the corpse–in life, a likeable panhandler known as “Johnnie Dollar.” For LeDuff, his fate is a macabre metaphor for the ruin of his hometown.

LeDuff came back to Detroit after a stint at the New York Times; he claims he quit because his bosses there complained that he was only interested in “losers.” A cover blurb says he returned to “discover what destroyed his city.” But while LeDuff ticks off the usual list of economic and historic forces—the shortsighted auto bosses, the riots of ’67 and the subsequent flight of the (mostly white) middle class, the cronyism and corrupt politics—he is essentially a storyteller. And because his family’s troubles are hard to separate from the city’s, his stories mix reportage with memoir.

For years, his mother valiantly tried to keep her downtown flower shop open, through armed robberies, arson, and vandalism, before finally moving her business to affluent Grosse Pointe. His sister became a streetwalker, a familiar sight in certain Detroit bars, then died in a car crash. A niece died from drugs; his brother lost his job in the (sub-prime) mortgage business and ended up in a low-paid job cleaning screws manufactured in China. And LeDuff isn’t detached from the pain. A domestic brawl with his wife landed him in a jail cell: “I felt bad, hollow,” he writes. “A middle-aged fuckup crumbling under the bulk of a dying city.”

LeDuff is a strong writer, in a Hemingway, tough-guy mode. But wondering if Detroit really did his family in, or if they would have struggled anyway, I found the personal stories less absorbing than his gutsy investigative reporting.

LeDuff follows a paper trail to see why $20 million to fix up a police precinct and firehouse never found its way there. “The floors … were cracked, the heat didn’t work and water pipes to fill the fire engines were forgotten.” Things get scary when he reports the killing of a murder witness—but his work pays off when, to everyone’s surprise, the judge doesn’t dismiss the case. “Your article put a lot of pressure on everybody,” she tells him. Three people actually do time.

When seven-year-old Aiyama is accidentally killed by a cop in a police raid, the physician doing the autopsy tells LeDuff that the girl died from the “psychopathology of growing up in Detroit. Some people are doomed from birth because their environment is so toxic.” Tragic as they are, the stories of Aiyama and so many other lost Detroiters deserve to be told. Few recently have told them better than LeDuff.