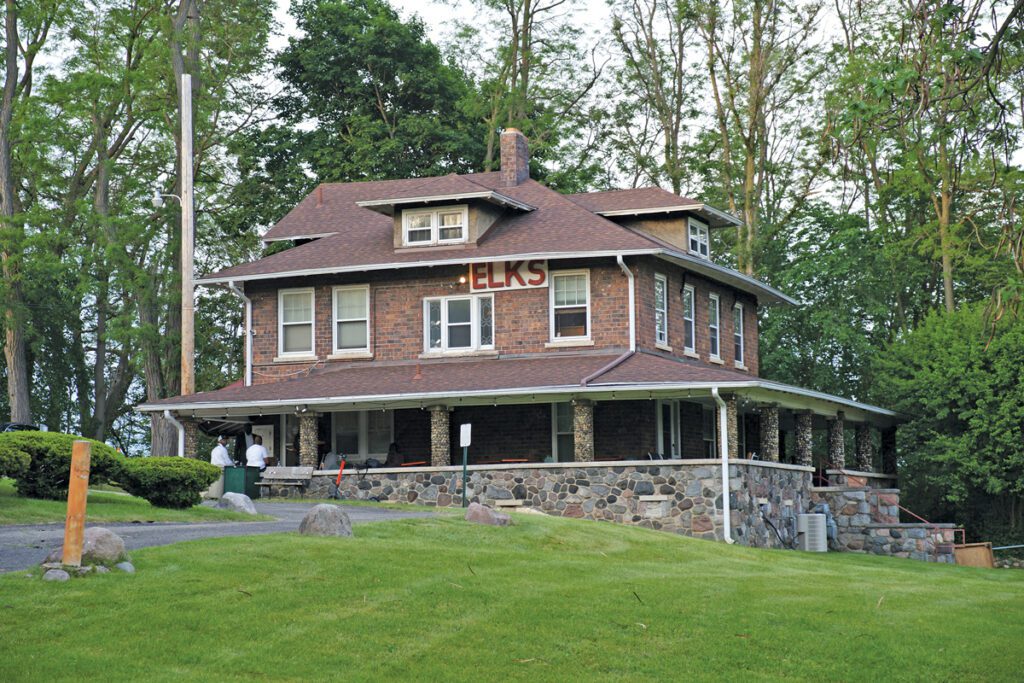

The city wants to raise $370,000 to repair and restore the Black Elks lodge on Sunset. | Photo by J. Adrian Wylie

The James L. Crawford Elks Lodge has a commanding presence at the northeast end of Sunset Rd., high on a hill overlooking the Huron River. The substantial brick-and-stone building has been a pillar of Ann Arbor’s Black community for eight decades.

For this reason, it has been chosen as one of three A200 Legacy Projects. These fundraising campaigns, launched by the city of Ann Arbor, are just some of the many ways the city is observing its bicentennial.

The building that now houses the Elks lodge began its life at the end of the nineteenth century as the home of Paul Tessmer and his family. Tessmer ran a boat livery at the foot of the hill, with an inventory of 160 canoes that he built himself. (The livery later moved across Argo Pond; now owned by the city, it still rents canoes, kayaks, and float tubes.)

Ann Arbor’s Black population grew rapidly in the 1920s, as a building boom and growing factories drew workers to the area. In 1922, they organized a local chapter of the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, also known as “the Black Elks.” A women’s auxiliary, the Daisy Chain Temple, followed a year later.

The organization started small, just thirty members meeting in the Colored Welfare League building on N. Fourth Ave. (now Fourth Ave. Birkenstock). But membership grew rapidly after the end of Prohibition, because Ann Arbor remained “dry,” allowing liquor sales only in racially segregated private clubs. “In those days, if you wanted a drink, you had to come to the Elks,” the late Sylvester Jackson recalled in a 1992 Observer article. “Noplace else would serve you.”

When the Black population surged again during WWII, the Elks bought the building at 220 Sunset. Jim Crawford, who served as Exalted Ruler for sixty-one years, told the Observer in 1992 that by then they had 400 members, and “ninety percent of the Black folks in Ann Arbor belonged here.”

For most of its history, the club was known as the Elks Pratt Lodge. By Elk tradition, it was named after its first member to die: Samuel Pratt, a truck driver who died at the age of thirty-eight. After Crawford’s death in 2003, it was renamed in his honor.

Over the years, the lodge has been the site of countless weddings and funerals; provided money, clothing, and food for less fortunate folks; and hosted family events like their yearly Easter Egg hunt.

But now the building is in need of repair and restoration. The $370,000 fundraising goal will fund improvements to structural supports, new windows, bathroom renovations, increased accessibility, landscaping, fencing, and a new coat of paint.

The second A200 Legacy Project is Bicentennial Park. Formerly known as Southeast Area Park, it sits across Ellsworth from the ever-popular Swift Run Dog Park, and across Platt from its picturesque neighbors, the city’s Scarlett-Mitchell Nature Area and Pittsfield Township’s Lillie Park. It’s home to two playgrounds, sports fields, and a basketball court. A half-mile paved path traces the perimeter, and in the evening the park perks up with games of softball and baseball on the lighted fields.

The city hopes to raise $2.65 million to make the park even more of a community asset. The crown jewel would be a universally accessible splash pad; other improvements on the wish list include upgrades to the rope-based playground structure and pavilion, new restrooms and, in keeping with the city’s A2Zero goals, solar panels with on-site energy storage. Donors who give $5,000 will receive a name plaque on one of four new picnic tables or on one of sixteen new benches.

At the newly renamed Bicentennial Park, the $2.65 million goal would pay for a universally accessible splash pad, solar panels with on-site storage, and other improvements. | Photo by J. Adrian Wylie

The city’s third and final Legacy Project is a statue of Kathy Kozachenko, the first openly gay person elected to public office in the U.S. A member of the radical Human Rights Party, Kozachenko was elected to the Ann Arbor City Council in 1974 and served a single two-year term. The statue is slated for installation near the entrance to City Hall.

The Ann Arbor District Library is celebrating the bicentennial with a new website, annarbor200.org. Over the course of the year, the website will post 200 items delving into the city’s history—articles, podcasts, animations, music, documentaries, and more, ranging from straight information to experimental art to Ann Arbor–style whimsy. Featured interviews include local historians Susan Wineberg and Bev Willis discussing Ann Arbor’s history through different lenses; Schoolkids’ Records founder Steve Bergman on the local music scene; and John Metzger, the third-generation owner of the namesake German restaurant.

Another AADL project, established by architect Norm Tyler and Realtor Tom Stulberg, is A2 Smart Tours. With other members of the Ann Arbor Bicentennial Tours Committee, they enlisted Ann Arborites knowledgeable about the city’s history, culture, architecture, and geography to develop fifteen self-guided tours spanning a total of 177 sites. The Ann Arbor Highlights Tour, for example, takes participants to such iconic locations as Michigan Stadium, Kerrytown Market & Shops, the Arb, and, of course, Zingerman’s Deli. The Underground Railroad Tour visits sites known or thought to be linked to the network that ushered escaped slaves to Canada before the Civil War. And the Scavenger Tour provides twenty partial photos for participants to identify and visit.

The tours can be downloaded on a smartphone or printed out from the library website. Anyone who visits every site can claim a Bicentennial Recognition of Completion certificate from the mayor’s office.