“We can’t be the first state …

why wait and be last?”

–letter to the Ann Arbor Times News, 1918

In 1849, a special committee of the Michigan state senate issued a report recommending universal suffrage: allowing every resident of the state to vote. It would, the committee wrote, reflect the “importance of natural rights and equality, and the deeply-held American belief that government must derive its power from the consent of the governed–including women.”

It was a radical idea at a time when African Americans were still held in bondage in the south, Native Americans were considered citizens of other nations, and Michigan had only recently let married women own property.

It was too radical for delegates to the state constitutional convention the following year. The elected representatives–all white men–debated extending the vote to African Americans, Native Americans, recent immigrants, and women. In the end, only Native American men who did not belong to a tribe were enfranchised.

Recent immigrants never did get the vote–even today, they must complete a lengthy process to become naturalized citizens. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments after the Civil War gave African American men the vote, though the struggle against voter suppression continues to this day. Tribal members won voting rights slowly, state by state, over the next century. And Michigan women began a generations-long campaign that led to a state constitutional amendment in 1918 and the ratification of the federal Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

—

Starting in 1855, Michigan women submitted petitions demanding the right to vote at nearly every biennial legislative session. While sometimes the petitions were forwarded to committees, they more often died without any action being taken.

When the state constitution was revised again in 1867, women submitted two petitions. One called for removing the word “male” from the description of voters, the other for putting the question before the electorate. Both were rejected.

The Michigan State Woman Suffrage Association (MSWSA), organized in Battle Creek in 1870, helped persuade the legislature to hold a statewide vote in 1874. The separate, one-issue ballot said simply “Woman suffrage–Yes” or “Woman suffrage–No.”

Elated, more than 300 men and women met in Representatives Hall in Lansing to hear national suffrage leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton speak and to organize a statewide campaign. Despite their efforts, only one in five male voters chose “Yes.”

A tiny victory was won in 1881, when the legislature passed a law permitting any adult who paid school taxes to vote on school-related questions. In 1889 and 1891, the state house passed bills that would have let all adult women citizens vote in all local elections. Both were defeated in the senate–the second time, by a heartbreakingly close vote of 15-14.

“Municipal suffrage” was finally approved in 1893–only to be overturned by the Michigan Supreme Court, which declared that the state constitution did not give legislature the power to “create a new class of voters.”

—

After that rejection, Michigan women became bolder about demanding their right to vote. Many had focused on municipal suffrage, hoping to advocate for issues close to home such as better education, health, sanitation, and job opportunities. Activists also called for limiting access to alcohol, creating separate “reform schools” for girls staffed only by women, raising the age of consent, and longer prison sentences for rapists.

At the national level, Colorado and Wyoming had already granted suffrage, and two national groups had combined to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association. In Michigan, the next big opportunity came in 1906, when another constitutional convention was scheduled.

By then, women’s suffrage and alcohol prohibition had become politically and socially entwined. Though worried that the association could alienate male voters, suffrage leaders teamed up with prohibitionists and many other groups to lobby for shared goals–and once again were disappointed. The 1908 constitution extended the franchise only slightly, to all women taxpayers, and only to vote on local financial matters.

But suffrage was rising as an issue. That year, students at the Michigan State Normal College in Ypsilanti–now EMU–debated the question. Both female and male students organized pro-suffrage groups, selling buttons to raise money and tasking themselves to campaign in their local communities when they went home on summer break.

The Normal College was ahead of the University of Michigan, which wouldn’t have a campus suffrage group until 1911, a year after Ann Arbor suffragettes first formally organized. Part of the reason may have been that in the early 1900s, about 80 percent of students at the Normal College were female while women comprised only about 20 percent of students at U-M.

In general, Ypsilanti was the more progressive of the two cities on suffrage. The presidents of the Normal College and Cleary College both supported and lectured on behalf of the cause, while U-M president Harry Hutchins hedged on the issue. And while the Ypsilanti Daily Press was an early defender of the cause, reporters for Ann Arbor’s Daily Times News used it as fodder for jokes.

U-M medical dean Victor Vaughan and his wife Dora Vaughan were active supporters, but they were in the minority. One suffragist complained that the university and its faculty were “at least fifty years behind” other schools in their attitudes toward the cause.

—

In 1912, governor Chase Osborn, a Progressive, called a special legislative session to once again consider a constitutional amendment granting full suffrage. It was put on the fall ballot. But “Michigan had not made their intent to put the issue on the 1912 ballot known to the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and therefore we were not selected as one of the states it would focus on,” explains Zoe Behnke, who with Jeanine DeLay and Linda Fitzgerald helped research the 2011 exhibit Liberty Awakes in Washtenaw County: When Women Won the Vote. “They said that they would send speakers but [local suffragists] would have to pay the costs.”

Ann Arbor’s town and gown groups merged to plan and fund the events. On a shoestring budget, some of which they raised by selling stationery that listed suffrage arguments along one side, they opened a headquarters at 205 E. Washington. Hundreds of pamphlets were printed and delivered around town while women’s clubs debated and discussed the issue.

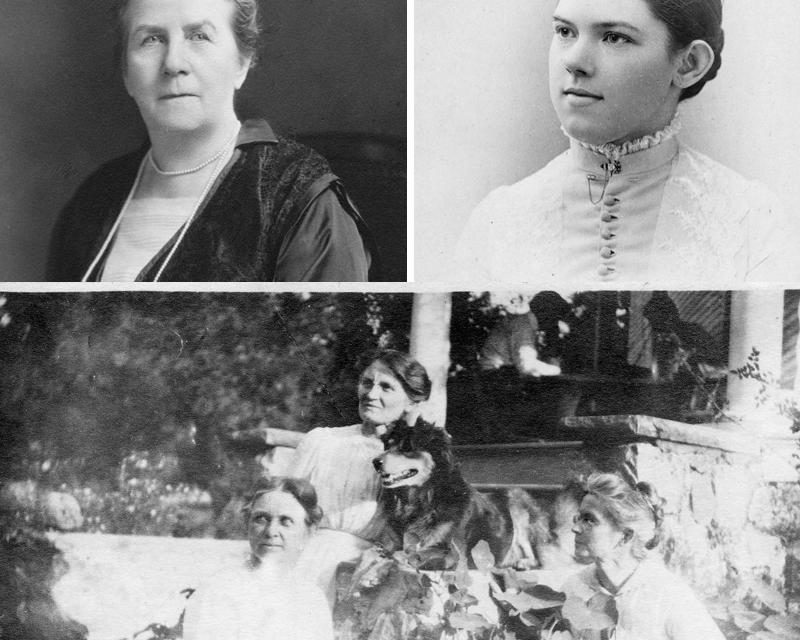

Many local women lent their talents in multiple ways. Mary Hinsdale, a professor at the Normal College and an officer in the Ann Arbor Equal Suffrage Association, lectured at women’s clubs. Association member Maria Peel, an insurance agent, volunteered as suffrage reporter for temperance groups and the women’s clubs. The clubs initially voted against suffrage but later reversed themselves, a feat largely attributed to Peel’s efforts.

Jennie Buell’s suffrage work naturally fit with her advocacy on behalf of local Granges, which mobilized farmers around common causes. Based in Ann Arbor, Buell lectured all over the state, served as editor and contributor to Grange publications, and traveled to other states to lecture on Grange opportunities for women–while also advocating for their right to vote. Other supporters included temperance groups, women’s clubs, and African American groups.

In November, Ann Arbor men voted in favor of suffrage, though Washtenaw County as a whole voted against it by a narrow margin. Heartbreakingly, Osborn’s initiative lost statewide by just 760 votes.

Supporters suspected fraud, blaming liquor interests and political bosses for stealing the vote. The Michigan Equal Suffrage Association produced flyers listing ways in which the vote was tainted by irregularities, including more ballots being cast in some precincts than there were total voters and anti-suffrage literature placed in the voting booths.

Suffragists called for another election the next year, counting on the anger over those issues to help them carry the day. Unfortunately, anti-suffrage groups were ready and waiting to launch their own campaigns; the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage quickly opened a chapter in Washtenaw County. Saloon owners and anti-temperance groups campaigned hard, and suffrage was defeated again; even Ann Arbor men voted the measure down.

Other states also voted on women’s suffrage in those years, some approving it, others rejecting it. After several defeats in 1915, Miss Lucy J. Price, an employee of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, wrote for the United Press to declare that suffrage “has seen its height.” The association’s president, Mrs. Alfred Dodge, was jubilant, opining that if women wanted access to the vote, they could “get it through their husbands.”

Yet just three years later, Michigan voters reversed themselves and approved a suffrage amendment. The following year, when Congress passed the Nineteeth Amendment, Michigan legislators voted unanimously to ratify it. By August 1920, after three-quarters of the states had ratified, women’s right to vote was enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

How did sentiment change so quickly? After the defeats in the mid-1910s, suffragists had regrouped and carried on. Reflecting a new push to “organize, organize, organize,” local suffragist Lucia Grimes made an indexing card system to track who knew whom and the positions of local politicians and organizations.

World War I also changed perceptions as women entered the workforce to replace men who’d gone to fight. Many, DeLay says, worked “in dangerous factories, doing munitions work. Thousands of nurses went to France with the Red Cross to help with the 1918 flu. Women were beginning to be perceived as accomplished, which helped lead to the cultural shift.”

On the eve of the 1918 election, the Daily Times News published supportive letters from prominent citizens. “I have often wondered why the women have been deprived of this privilege,” wrote Albert Fiegel, of Fiegel’s Men’s Store. “I have never heard a good sound reason that proves that judgment of women would not be as good as that of men’s.” He urged readers to “consider the women we live, love, in general–shouldn’t they have the same right to vote as men? How would men feel if conditions were reversed? We can’t be the first state … why wait and be last?”

—

Maria Peel kept smashing glass ceilings after suffrage was won. She served as the city’s first policewoman, the county’s first female truant officer, a juvenile probation officer, and worked for the Friend of the Court.

Even before ratification, the leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association moved on. They organized the League of Women Voters to, in the words of the group’s website, “help 20 million women carry out their new responsibilities as voters.” The Grange’s Jennie Buell was one of its first presidents.

Other activists set a new political goal: an amendment to give women full equality under the constitution. Fifty years later, the Equal Rights Amendment was approved by Congress with the support of a new generation of feminists, but a conservative backlash stalled ratification and it remains unrealized.

There are many lessons to take away from the tireless work of the suffragists and all voting rights activists, but the foremost one is to remain vigilant to protect all Americans’ rights at the ballot box. Says DeLay, “We tend to fall asleep and so liberty must awaken.”