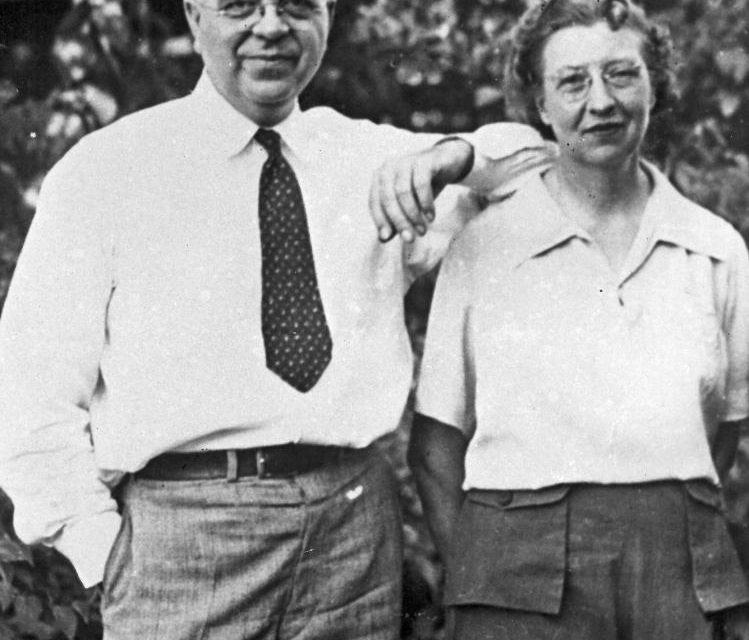

When Eugene Leslie and his wife, Emily, left their northside home to the City of Ann Arbor for a “children’s park,” it’s very unlikely they envisioned a bald eagle settling its feathers in their backyard, or a ball python in the small outbuilding they used to extract honey from beehives. It’s a safe bet the Leslies did not picture the poet Allen Ginsberg and composer Philip Glass traveling from New York City to meet in their living room, planning a meditation center led by a Tibetan lama. Still, those who knew the Leslies believe they would be deeply pleased with the many forms their gift has taken. The Leslie Science and Nature Center (LSNC), celebrating its thirtieth year, is the vibrant centerpiece of their legacy, along with Leslie Golf Course, Leslie Park, and Leslie Woods.

Eugene Leslie came to Ann Arbor in 1919 from New York City to teach chemical engineering. Along with a teaching position, he was seeking refuge. New York had been good to him in some ways–he met his future wife, the tall, redheaded Emily Ebner, when they were graduate students at Columbia University–but in other ways, big city life had become intolerable. A PhD chemist whose research on synthetic acetone contributed to the improvement of TNT during World War I, Leslie came to regard New York City’s subways as “rat tunnels.” He wrote in his autobiography: “After two years of this highly artificial existence, I was ready for a nervous breakdown.”

Early twentieth-century Ann Arbor offered the Leslies the mix of city and country they desired. In 1923, they purchased a home on a few hilly acres on Traver Rd. in countryside north of town.

Even as Dr. Leslie established the U-M’s graduate program in chemical engineering, he continued to do consulting work in the petroleum industry. In the late 1920s, he left the university to run Leslie Laboratories on the Traver Rd. property, which the couple had been steadily expanding. It eventually grew into a working farm of more than 200 acres.

Mrs. Leslie devoted her considerable intellect to raising Hereford cattle, chickens, and hogs, and growing the crops to feed them. Dr. Leslie developed a hay dryer to shorten the time needed to produce winter feed. Raspberries, strawberries, blueberries, currants, peaches, apples, pears, and cherries were all grown and sold at the Leslie Farm.

Their niece, Judith Ebner, recalls visits to the farm in the 1940s:

“Uncle E.H. often worked at a desk on the first floor that faced east. My twin brother and I were probably about six. As we came in the door, he would look up from his desk and say, ‘Emily’s in there.’ He never stood up, just pointed us to the door in the next room. He was of the school, ‘Children should be seen and not heard’–that old philosophy. So, I never talked with him much as a small child. He was always working on something. Uncle E.H. was a workaholic, brilliant.

“My aunt, Mrs. Leslie, was probably the most fabulous conversationalist you would ever meet. She was very well read, valedictorian of her high school. She was very bright, president of the Garden Club in Ann Arbor. She was very interested and involved in the farm things. She was from a German family and grew up in Atchison, Kansas. They all must have learned how to drink beer. She liked warm beer. So in the closet, in the kitchen, that’s where she kept her warm beer.

“They never had children of their own, but they loved children. They had all these kids here. It was the children in the neighborhood who came and played. That’s where the genesis of the idea started.”

—

Tracy Coates, now a salesperson at Dunning Toyota, recalls an idyllic childhood playing on the Leslie property:

“When Traver was a dirt road, when there wasn’t a church or David Ct., my parents bought one of the first houses built there in 1960 or ’61. It was all young families, and there were probably forty kids within five years of each other. It was a very cool place to grow up.

“If you walked around the front pasture where Project Grow is now, there was just a big hole cut in the fence. So you’d have to duck through the hole to get onto the path, and then we kids just lived in those woods.

“But the Leslie house was kind of scary, at first. On Halloween it was always a dare who would go up to the Leslie house. I think just because we were little kids and we didn’t know them–which was funny, because we were all over their yard, we had forts all over the woods, and of course we lived at Black Pond –but nobody ventured up to the house.

“If you went up to the house on Halloween, Mrs. Leslie would give you a big Hershey bar–one huge one per kid–but they also had shotguns leaning against the inside of the door. Looking back now, I think that was because they were rural, they grew up in a different generation. So going to the door was kind of exciting.

“We played all over the fields and woods, but I was really drawn to the house; I loved it, and I really enjoyed being around Mrs. Leslie. She was this lady who lived in the woods with the animals; she was everything I wanted to be.

“I just remember feeling very safe and comfortable around her. I didn’t have to do or be anything; I could just write, and she would be there with me. She was tall and had her hair pulled back; she was right out of a Disney movie for me.

“I wrote them quite a long letter in elementary school about how important the property had been to me. Mrs. Leslie called my mother after she got that letter and told her they were going to donate the property to the city for kids.” At Emily’s funeral, Coates’ letter was read as part of the eulogy.

E.H. and Emily Leslie both died in 1976. They had already given their home to the city, retaining a life lease, and had sold the farm for annual payments of $15,000. They forgave the remaining debt in their wills, and left a half-million-dollar trust fund that more than covered the past payments.

It was one of the most generous gifts the city has ever received. The farm became Leslie Golf Course, Leslie Park, and Leslie Woods. The Traver Rd. property opened to the public in 1986 as the Leslie Science Center.

The word “Nature” was added to the center’s name in 2007 to reflect an expanding mission, notably including a recently arrived collection of raptors–rescued birds of prey, including hawks, owls, and a young bald eagle–that were used in educational programs. The same year, the center became a nonprofit, overseen by a board of directors. The city still owns the buildings and grounds and provides maintenance.

Cheryl Saam, who now runs the city’s canoe livery at Gallup Park, was one of the directors of the center in its early days. Her preschool-aged sons were sometimes the first ones to try out activities that were later incorporated into parks programs.

“Like all kids, they needed ways to burn off extra energy. One game we developed for summer camp was where you would start at the top of the hill between the caretaker’s house and the Leslie house and you’d run down the hill screaming. You’d see how far down the hill you could run, screaming, before your breath ran out. You had to stop where your breath ran out, where your scream ended.”

When Saam began work at the property, “the house was as if Dr. and Mrs. Leslie had just left and would return any minute. They still had a presence there. All their books were on the shelves; they were avid readers. There were tons of books on chemical engineering, of course, but there was also Eastern philosophy, farming–I remember one book titled, Eat Meat Three Times a Day. You’d open a drawer, and there was Dr. Leslie’s wallet.

“Mrs. Leslie’s journals were there. She used to itemize every expense. There was a notation for every Saturday night; they spent twelve cents on ice cream.

“My son Philip, who is now thirty-one, happened to be here at the time of Leslie Center’s thirtieth anniversary party [last fall]. I asked him if he wanted to go–not thinking he would–and he said, “Yes, I can still smell it.” I knew what he meant. Back then, we had dead animals upstairs, in boxes, in the bedrooms. It was stuffed raccoons and rabbits–preserved, but dead. Dr. Leslie’s dust-covered bedding was still there. Everything was if the Leslies had just closed the door and walked out. The place smelled a little musty and dusty.

“And there was Dr. Leslie’s chemistry lab. It was where the new MichCon Nature House is. It was in really bad condition; raccoons were living in there. There were beakers and other equipment, all of it smelling of chemicals. It also was as if Dr. Leslie had just walked out and locked the door.”

—

The books on Eastern philosophy would have helped Dr. and Mrs. Leslie appreciate a board meeting for the local Jewel Heart meditation center that took place at their house in the fall of 1990. Aura Glaser, one of Jewel Heart’s founders, had been married in the Leslie house that summer.

“Because we’d had a small wedding, my mother-in-law later arranged a kind of a reception party for us, inviting some of her friends. We’d had such a good experience at Leslie with our wedding, we rented it several months later in September for a sort of wedding celebration/reception. We rented it for the entire weekend, and, in doing so, we had extra days.”

The year before, Philip Glass and Allen Ginsberg had come to Ann Arbor to do a benefit for Jewel Heart. When they returned to Ann Arbor in 1990, their visit included an initial Jewel Heart board meeting. As Glaser recalls, “We had already rented a space at Leslie for the wedding reception–it was already paid for–so we decided, ‘Let’s have the board meeting there, it’s a nice environment.’ It was easy to put the two events together–the wedding reception and the board meeting. It was a warm and welcoming space with a kitchen available. There was plenty of space for us all to be.”

Unfortunately, there are no photos of the day Ginsberg and Glass sat in the Leslie dining room. “Allen was the photographer. He was the archivist. He was an incredible record keeper. All the photographs he made, he would write on the bottom who it was, where it was, what was going on. But I don’t believe he photographed that event.”

—

These days, the center cannot be rented for private events, and schoolchildren from across the county are found on the Leslie property, generally not poets and composers from New York City. The summer camp program–with some activities Saam developed long ago–has been a touchstone for scores of Ann Arbor families for decades.

This year, the center’s current director, Susan Westhoff, helped shepherd a “union” of Ann Arbor’s Hands-On Museum (HOM) with LSNC. The two organizations had been collaborating on some programs for years. By joining forces, she says, they are able to get the attention of donors neither could attract on their own.

“There are different funding sources–foundations–that really don’t look at nonprofits with an annual budget of less than $5 million,” Westhoff explains. “HOM is at about $4 million, and we’re around three-quarters of a million. So by combining, we get very close to the threshold where we’ll be seen by national funding sources.”

Westhoff emphasizes that they won’t “rebrand” the center. “It was really important to everyone involved in this union that this place, Leslie, remains in feel and in reality the same–that it has this campus feel; it’s part of a neighborhood. We really honor that. There is no intention for that to change.

“One thing I really appreciate about HOM’s board and staff is that they really see Leslie for what it is. So they’re looking to invest in the buildings not by radically changing them, but by helping the campus be as functional as it can be.

“The interpretive master plan for the site outlines things the Leslie staff would like to do. In the raptor enclosure, we’d like to have signage that interprets what a raptor is, where they live, people’s impact on their habitats. We bring school groups into the woods all the time; we’d like to have ‘teaching pods’–established spots where a group can collect around a teacher, where everyone can hear and see well rather than yelling down a narrow trail hoping everyone can hear.

“If we’re successful at this union, the everyday user shouldn’t detect a difference. Both places should look and feel as fantastic as they already are. If anything, they just see more opportunities offered and things are a little more updated.”

Tracy Coates, the neighborhood kid who grew up loving the Leslie property, sums up the Leslie legacy: “We were a suburban neighborhood, but we had this wild, amazing place. As Ann Arbor keeps getting developed, this place becomes even more rare and precious. All kids are different, what they need is different, but I think this kind of land gives something to everybody.”

from Calls and Letters, May 2017

To the Observer:

A few months ago the Observer published an article on Dr. Eugene Leslie (“Science and Nature on the North Side,” January). I’d like to fill in a few details about his life.

I met Doc Leslie in 1963. I moved to Ann Arbor to join the department of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, which he’d founded, and bought a house that he’d previously owned. On the front porch my wife and I found a bathtub, a sink, and a toilet, all crated up. The couple who sold us the house told us that Leslie had started to put a bathroom in the second floor, but ceased work after the township clerk told him that he’d need a building permit. They took it as an indication of his stubbornness.

He’d been on the faculty at Columbia, but resigned when his department head told him to cut down on his consulting for oil companies. He began a new line of research here, instituting the first forced drying of alfalfa, running experiments to learn the optimum height of the side slats of pig birthing pens, and introducing a system of upgrading the value of gravel by bouncing it on a steel plate. (Particles with no internal cracks bounced farther.)

Now back to our home. We had four children so we badly needed a second bathroom. I figured that enough time had elapsed that I could finish the second story bathroom without being noticed. I installed the fixtures, then hired a plumber to hook up my kitchen sink drain to our septic system–at the time, it emptied into Traver Creek.

He noticed that the drain from the new bathroom went straight through the basement floor. I had my wife flush the toilet while I looked at the end of a pipe near the brook. Sure enough, a gush came out, so I had him change that, too. Doc Leslie had surely known that–perhaps another reason he ceased work on that bathroom.

Sincerely,

William Hosford