Many Civil War reenactors assume personas of the famous: “Honest Abe” Lincoln; Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee. But in his one-man show, “Near as I Remember,” Rob Stone plays an ordinary Union veteran–named “R.E. Stone.”

“It was people like me who won the war,” he explains. “I’m playing a role, and I’m enough of a ham that I can do it.” He hasn’t traced his genealogy but suspects that, like many reenactors, he had ancestors who fought in the conflict.

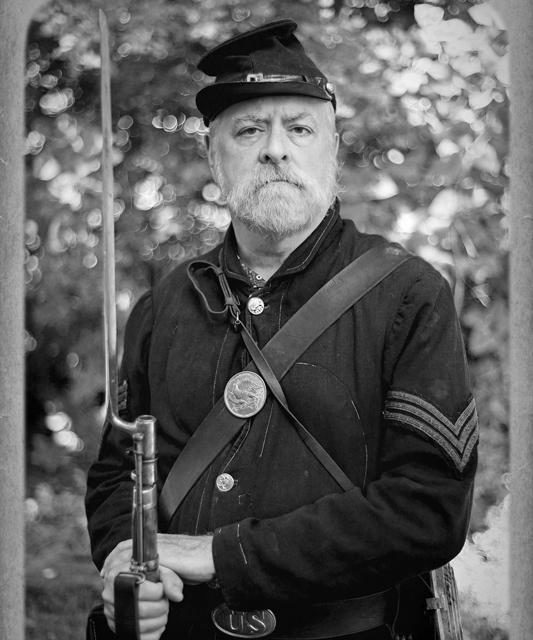

His white beard and mustache set off by his blue uniform, Stone stands in front of an audience at the Pittsfield Township Community Center, and introduces himself as a veteran of the Seventh Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment (which actually fought at Gettysburg and elsewhere). He explains his apparel and knapsack and opens a case to show his musket and bullets including one that’s 150 years old. Then he fields questions from an attentive, serious audience.

“What is your uniform made of?” a young boy asks shyly.

“The shirts are of muslin,” Stone, sixty-five, replies. “Thank God they don’t have to be made of wool. The hats are all made of wool. In summer you smelled it a lot. “

“What do you eat?” a grown-up asks. “Hardtack,” Stone answers–a tough biscuit slapped together from flour, water, and salt. In good times, Stone says, the men roasted beans.

“After the war, did you attend regiment reunions?” asks one man.

“No,” Stone says emphatically. “After four years of seeing friends die, I’d had enough.”

—

Stone stays in character throughout his performances and appreciates that his audiences play it straight, too. “No one asks me about the Internet or the airplanes … People really do want to get a sense of the daily activities of the soldier.”

He meets me at RoosRoast Coffee on Rosewood, near the home he shares with his wife, Cathy, a teacher at Abbot Elementary, and their son Justin, a Skyline senior and Eagle Scout. (Two adult daughters, Sarah and Adrienne, live out of state.) In a nondescript T-shirt and casual pants, Stone explains he’s been fascinated by the Civil War ever since his dad, an auto parts salesman, took him to visit the Gettysburg battlefield, a few hours from their home in Philadelphia.

Decades later, living in Ann Arbor, Stone found himself looking for a hobby as a diversion from a demanding job as marketing director for a Christian book distributor. His wife suggested he explore Civil War reenactments, which exploded in popularity with the war’s centennial in the 1960s and got a further boost from Ken Burns’s 1990 PBS series The Civil War.

Stone took part in reenactments, enjoying the drama of dressing in uniform, marching in procession, and shooting black powder muskets in “battles.” He was thrilled to join thousands of extras in the 1993 film Gettysburg, partly filmed on the historic battlefield. If you don’t blink, you can glimpse Stone in the film. “To my family’s lasting embarrassment!” he says.

A graduate of Palm Beach Atlantic College, now University, a small, Christian school in Florida, Stone moved to Ann Arbor in 1975 to do a master’s in history at U-M. He spent his career in publishing, finishing at Oxford University Press, where he promoted its line of Bibles and some reference books. A longtime member of the Ann Arbor Civil War Round Table, upon retirement Stone decided to launch “Near as I Remember,” which he hopes will interest schools as well as community groups (he charges $50, plus mileage, for a performance). He’ll tailor presentations to include subjects like poetry and song in the war; soldiers’ letters and diaries; and how friends and relatives managed on the home front.

—

When I call Stone with follow-up questions, I reach him in the thick of a reenactment in Marshall. “There are all kinds of activities going on!” he reports. “A battle this afternoon. A fashion show [of period clothing]. A gentleman who presents himself as Abraham Lincoln who gives a lecture. Blacksmiths.”

The reenactments draw spectators as well as participants. “I think the general public realizes they’re coming to see us as an opportunity to learn more about the Civil War, and the soldier’s life,” he says.

But the war’s complicated legacy remains unresolved. “In many ways, it was the wound in American history that never really healed,” reflects Stone.

Debates over removing Confederate monuments have mounted, particularly after white supremicist Dylann Roof killed nine African Americans in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015. One camp says that statues of slaveholders like Robert E. Lee glorify an evil system, while others argue that the removal is an erasure of American history, ugly or not.

Some reenactors are arguing about the question, too, Stone says. “It’s really a sore point.” Mostly your typical Ann Arbor progressive–he’s criticized Trump on Facebook, and is active in the liberal St. Clare Episcopal congregation–Stone at first equivocates. “I don’t know if anyone really has an answer to that,” he says. But he adds, “I don’t see how we can eradicate that history, because we would be denying it.”

For the same reason, he respects efforts to make military history more inclusive of all the parties caught up in America’s wars. A new Philadelphia museum on the American Revolution, he points out, goes beyond the lives of “Caucasian American colonists” to talk about the plight of slaves, many of whom fought for the British in exchange for promises of freedom.

Stone says that his impersonations, like the reenactments, don’t try to resolve the “larger issues.” But he aches to bring the history of individual soldiers to life.

“Nobody today can really grasp what it was like to live in another era,” he says. But he hopes his performances offer at least “a sidelong glance” into history as it was lived.