A distraught woman stares into the middle distance against an ominous red background; from a jagged voice bubble comes her anguished cry: “… NOW WHAT?” The words above her head, jauntily angled, reveal the source of her torment: “A DEGREE IN THE HUMANITIES!”

Give the U-M Institute for the Humanities interns points for creativity: This is an event poster for a career panel. And the question applies not just to students on the brink of graduation—it can also be asked of the humanities as a whole. According to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Humanities Indicators, the number of humanities degrees is on the decline at all academic levels across the world.

LSA associate dean Tim McKay calls it an “evolution” reflecting “a blurring of disciplines.” | Photo: Mark Bialek

Between 1990 and 2010, the humanities consistently accounted for 14–15 percent of U.S. bachelor’s degrees; by 2020, the most recent year for which data is available, they had fallen to 9.7 percent. Master’s degrees shrank from 5.3 percent in 1997 to 2.7 percent by 2020. And doctorates dwindled from an 11.1 percent share in 2000 to 7.2 percent in 2020.

Is the same happening at U-M?

“It would be very strange if it were not,” Tim McKay says with a reassuring chuckle. The associate dean for undergraduate education at the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA), McKay has a cheerful manner, intelligent eyes behind rounded spectacles, and a physics degree. “It is of course the case.”

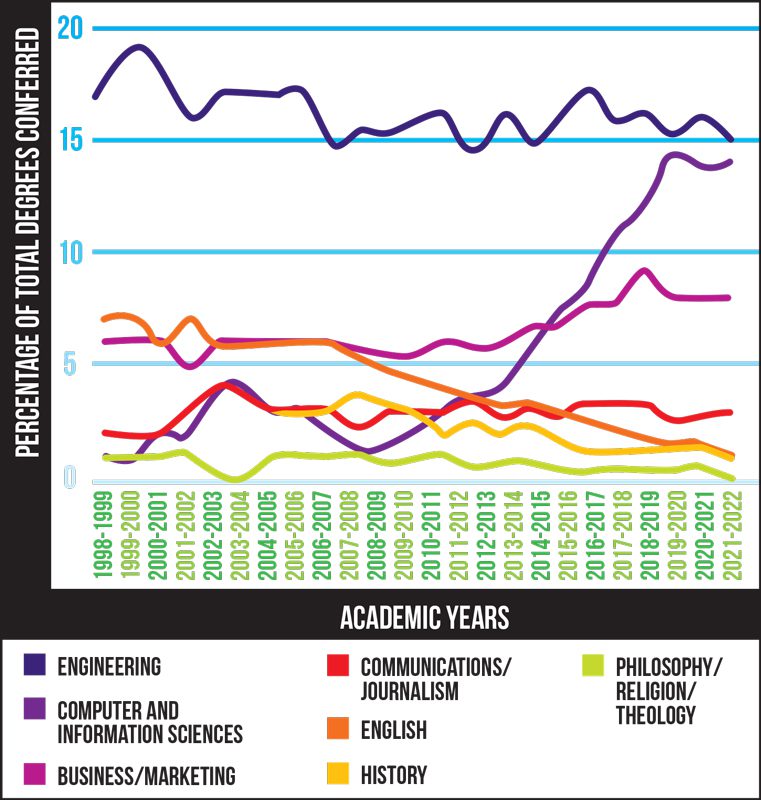

According to U-M Common Data Sets, in 1998, English majors made up around 7 percent of graduates; by 2022, they were a mere 1 percent. History majors also made up 1 percent of grads that year—in 2008, they had been 3.6 percent. The number of philosophy and religion degrees was so low it didn’t even register.

Meanwhile, engineering has held an average 16.2 percent share of undergrad degrees since 1999. Computer and information science degrees skyrocketed fourteen fold to second place. Of the top ten LSA majors, half are STEM fields and four are social sciences, leaving one lonely discipline to represent the humanities: communication and media, clocking in at number eight with 209 graduates.

From the numbers, “I think you can get a false sense from this narrative that the humanities are disappearing, that students are not studying the humanities, or that they’re not interested in the humanities,” says McKay. “But the general influence of the humanities—English in this case—on students isn’t very different.”

The reason? U-M’s general education requirements, which include writing, humanities or foreign language, and social sciences. On top of that, any LSA degree, regardless of major, requires seven to ten credits of humanities courses. Even engineering majors are required to complete sixteen credits in the humanities.

McKay describes the dwindling number of humanities majors as an “evolution” that reflects “blurring of disciplines” as more faculty hold multiple appointments and offer more interdisciplinary classes. And he points out that some humanities majors—such as communication and media and film, television, and media—are holding steady.

“These are subjects that are engaging with storytelling and the work of literature in modern forms,” he says. “Students see them as effective, powerful modes of expression for the future.”

—

Engineering, computer and information sciences, and business/marketing dominate U-M undergrad degrees, while English and history have plummeted.

What does the trend say about the meaning of a college education? Have lofty goals of intellectual enrichment been traded in for cold, pragmatic job training?

“Since the arrival of the modern university … around the turn of the twentieth century, there’s always been this tension, or unresolved question: What is college for?” says Jim Tobin, author of Sing to the Colors: A Writer Explores Two Centuries at the University of Michigan. “With some people expressing the minority view that it’s for … self-realization and thinking about the larger problems that life poses to everybody, and on the other hand, preparing for a career.”

“We have to be careful of a nostalgic image that in 1955, everybody at the university was reading Tolstoy,” says historian Terry McDonald, whose forty-five years in academia include eleven years as dean of LSA and nine as director of the Bentley Historical Library. “At their very peak, and that was the late sixties, early seventies, about 12 percent of men and about 22 percent of women students had any kind of humanities degree. So the humanities have always been a minority of the college degrees in America.”

That time period, McDonald points out, was one of economic prosperity, abundant job opportunities, and affordable tuition. Nowadays, four years of in-state tuition at U-M cost almost $75,000; out-of-state tuition is more than three times that figure. Is it any wonder students and their parents expect a financial return on their investment?

McDonald says the recession of 2008 was a “huge and terrifying lesson [that] demonstrated how fragile one’s economic circumstances can be.” Afterward, he notes, there was a nationwide drop in law school enrollment, which in turn may have contributed to the dip in prelaw humanities disciplines like history, philosophy, and English.

U-M senior and art history/anthropology double major Evalicia Chavez says that among her peers, “there’s a good bit of cynicism right now, especially with anything work- or economic-related. But I also think some of it is a fear of instability.”

McDonald suggests another possibility: the plugging of the “leaky pipeline” that for decades dissuaded women from studying STEM fields.

“Women who were fully qualified to succeed in the sciences were basically driven out of those disciplines by a combination of gender bias and bad teaching,” McDonald observes. “One of the things that’s happening is the shift out of the humanities among women who simply have more choices now.”

Yet another factor could be changing learning styles. Earl Lewis, professor of history and founding director of the U-M Center for Social Solutions, says the slow, analytic pacing of humanities material might be challenging for Gen Z.

“I think we live in a period of instant gratification, where you can pick up your device and send a message and get a message back in fifteen seconds,” he says. “And then [your teacher is] saying, ‘Okay, but I want you to read Shakespeare.’”

—

Considering the forces at work, perhaps the question isn’t why fewer students are choosing to study humanities, but why some still do. Chavez’s family urged her to pursue math or engineering, but a year of Zoom math classes during the pandemic deterred her.

“It was a pretty miserable experience. I feel like there’s no point in trying to sugarcoat that,” she says. “And so it was like, ‘I need something that’ll make me happy.’”

That something was art history; she is currently applying to PhD programs and aims to work in a museum.

For Lewis, that question also arose as a result of Zoom classes. Teaching a history course during the pandemic, he noticed that many of his students weren’t from LSA. Why, he asked them, were they taking a non-required history course? Their answer: to learn something they didn’t get to learn in high school.

A career panel last year reassured grads. | Photo: Lon Horwedel

In an age of profound uncertainty, in the midst of a pandemic, the digitized faces arranged in the neat grid of the virtual classroom wanted that most essential college experience: to expand their horizons.

“There are a lot of students who want to learn, and college provides them with the opportunity to gain exposure to topics of interest that … in some cases results in them changing their majors,” Lewis reflects. “It’s a certain kind of serendipity that I think is still a golden aspect of the college experience.”

That’s what happened to Kevin Lane, one of the participants in the humanities career panel: He abandoned a premed track in his junior year for a BS in philosophy and English literature. The reason: an Intro to Philosophy elective.

“I really loved that class so much,” Lane says with a charming crooked smile. “It was the first time I really was able to discuss some of these big ideas of who we are, what things mean, individuality, freedom.”

One fateful day, Lane woke up early to volunteer at a bio lab at 7:30 a.m. He bounced between the lab and class all day, finally finishing his work at 2 a.m. Staggering outside, he sat on the front steps and realized that he couldn’t do this anymore.

“Science is so powerful in being able to understand the external world … but it almost literally cannot say anything about experience and subjectivity,” Lane reflects. “Through the humanities and expression of art and creativity, and how we relate to each other, and really settling into what it means to be a human—that is the way that we can understand these things in an intelligible way.”

In other words, it took the humanities to help a premed student understand what it means to be a human.

Junior Mikey Delphia has been interested in Japanese history since he was a kid—his mom is Japanese, and he spent part of his childhood living there. But even as a “pretty pessimistic middle schooler,” he says with a wry smile, he figured “a humanities degree isn’t gonna get me too many jobs. … What can make me money and is tangential? Economics.”

But in college, he realized his love of Japanese history wasn’t going away. Rather than waste the groundwork he’d laid toward an econ degree, he’s pursuing a double major and studying both.

He’s not alone: Nationwide, humanities degrees make up 23 percent of second majors. McDonald describes this phenomenon as students choosing a career major and a love major.

“The way they’re adapting to it, I think, says some very great things about the students of today,” he says. “They’re finding a way to pursue those interests.”

—

The U-M Humanities Career Panel is decidedly more cheerful than its event poster. Five recent humanities grads perch on tall director’s chairs and attempt to answer that question—NOW WHAT?—by sharing their experiences at and after U-M.

For some, their degrees translated directly into professions: Creative writing major Clara Scott now works as a copywriter, and Dani Williams graduated from student to project coordinator at the U-M Department of Afroamerican and African Studies. Ali Elatrache, meanwhile, spun a BA in French and anthropology into a job as the development associate lead at the Michigan Theater Foundation; Jacquelyn Timoszyk snagged an account executive position at Google with a BA in history and German; and Kevin Lane put his BS in philosophy and English literature to work in the world of community organizing.

Like Lane, Elatrache and Timoszyk switched from STEM fields, but for Williams and Scott, a degree in the humanities was always part of the plan. While they didn’t graduate with a credential for a specific job, they did acquire a suite of so-called “soft skills”: distilling and analyzing information, organization, creativity, problem-solving, verbal and written communication—and, in Earl Lewis’s words, the ability “to sift through a lot of the junk that’s out there” by learning “to be discerning consumers of information.”

In a previous role, as president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Lewis launched a $4.27 million project called College and Beyond II (CBII); Tim Mc-Kay was a co-principal investigator. The researchers compiled student transcript data spanning twenty-one years, nineteen public colleges, and more than one million students studying liberal arts, professional fields, and sciences to analyze the importance of the humanities.

“While there are lots of impassioned defenders of the liberal arts and humanities that have some really strong arguments for their value, a lot of that is not necessarily backed up by empirical evidence,” says Allyson Flaster, who joined the study as an assistant research scientist in 2019 and now serves as the principal investigator—and who, incidentally, holds a BA in visual art. “The Mellon Foundation wanted to collect data that researchers could use to empirically test these arguments.”

CBII also surveys graduates, asking not just about careers, but also about well-being and civic engagement—after all, there are other ways beyond jobs in which people contribute to their communities.

Living in a participatory democracy, “our lives are shaped by… talking and writing and speech,” observes Delphia, the econ–Japanese history double major. “This might be a stretch, but I think the humanities major can help you be a better citizen.”

It might not be a stretch at all. Although Flaster notes that it hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed—fixing me with a deliberate gaze through her thick-rimmed glasses, silently warning against drawing premature conclusions—she says that “our initial look at the data suggests that humanities and social science graduates have the highest levels of democratic engagement.”

Few students would choose an academic discipline with that goal in mind. But the skills Lewis describes may be increasingly valuable. In the age of fake news, bots, and artificial intelligence, humanities majors are equipped with the critical thinking skills to discern which information can be trusted.

Of course, these are the very technologies that increasingly threaten to replace white-collar occupations—from copywriting to coding. At one end, Lewis observes, blue-collar workers are being replaced with automation, and at the other end with algorithms.

“So then the question becomes,” he muses, “what do you do with humans, in a world of increasing automation?”

Will there be a tipping point? And if so, are humanities majors, with sharply honed skills in critical thinking and creative expression and increased likelihood of political engagement, perhaps uniquely poised to give voice to the displaced—or to a resistance?

In which case, are humanities perhaps more relevant than ever?