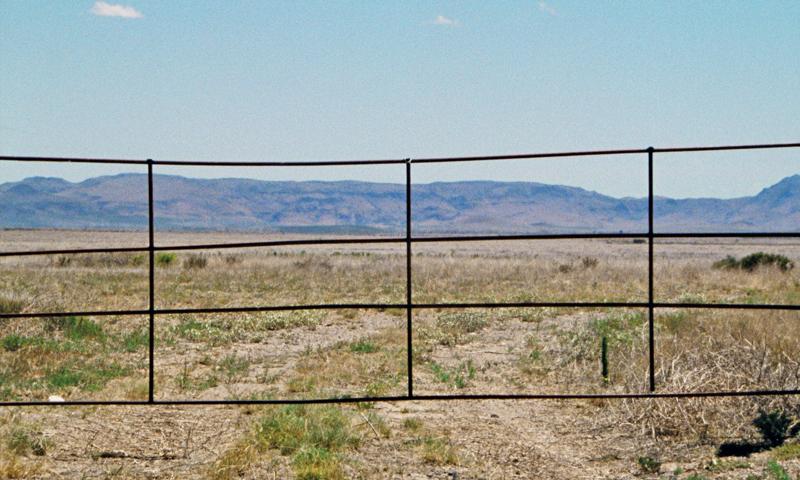

There’s slow-burning horror in the lengthy opening shot of J.P. Sniadecki and Joshua Bonnetta’s film El Mar La Mar. It at first seems to depict an indeterminate natural landscape split into multiple small images by some sort of prismatic effect, with a moving camera creating a sense of ecstatic energy. As the camera slowly pulls back, it’s revealed that we’re actually peering through the tall bars of a section of border wall, fragmenting our view of the Sonoran Desert beyond.

This interplay of natural beauty with stark reality is the bread and butter of Sniadecki and Bonnetta’s hypnotic, disturbing portrait of life—and gruesome death—along the U.S.-Mexico border. The filmmakers’ narrative couches the hot-button issue of immigration in uniquely elemental terms. Rather than casting the issue in terms of Americans versus Mexicans, or border patrol versus asylum seekers, the film’s great antagonist is the desert itself.

Sniadecki and Bonnetta compose painterly shots of sunsets and moonrises over the sandy expanse, but their interview subjects return time and again to the horrors the desert holds for those attempting to cross it. Multiple voices discuss how easily footprints are blown away by the wind. One man, speaking in Spanish, describes getting separated from his group while attempting to cross the border on foot because he stayed behind to help an old man who fainted in the heat. “You get lost because you don’t know where you are,” the man says.

People also tell stories of stumbling across dead bodies in the sand. “For me, the thing that just enraged me was how something so horrible was no different than the various cattle corpses we’d come across in the field,” one woman says.

None of the film’s interview subjects are seen onscreen. Their haunting tales are often accompanied by a black screen, or more landscape footage. There are long wordless stretches too. In these, the only sound is the ambient hum of desert wind or buzzing insects, while the camera lingers on unsettling details like faded clothes left behind in the desert or the water jugs that activists leave out for thirsty migrants.

Sniadecki and Bonnetta’s sympathies are clearly with the immigrants, but they make a smart decision in casting the desert itself as their film’s focal point. By denying us even a glimpse of their interview subjects’ faces, the filmmakers strip away some of the prejudices we might assign to them, placing them all on the same side of a battle against the elements. In uniquely compelling terms, they raise one of the most relevant questions in the ongoing immigration debate: what horrors at home would prompt someone to contend with such an utterly unforgiving swath of nature?

The film screens November 6 at the State Theatre as part of the Ann Arbor Film Festival’s “AAFF Presents” series.