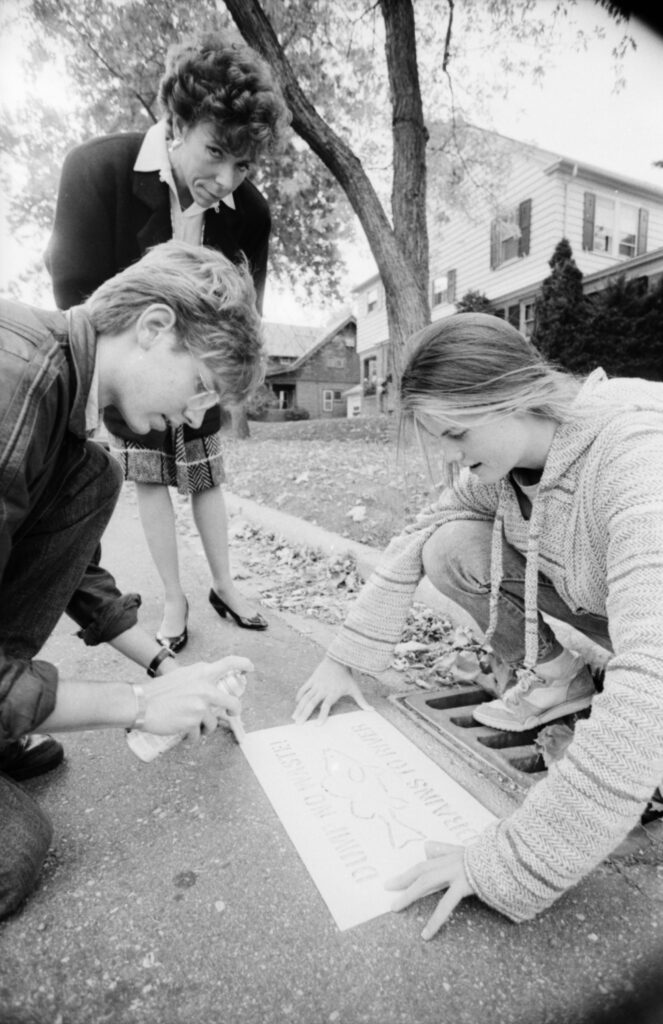

Elected as drain commissioner, Janis Bobrin orchestrated a title change to water resources commissioner. In 1990, she watched as students stenciled messages urging people to respect storm drains.

“When I drive around, all I see is what used to be here,” says Washtenaw County water resources commissioner Evan Pratt.

What used to be here were swamps. The landscape was so wet that during the first wave of settlement in the Northwest Territories, “Michigan was passed over,” says Pratt’s predecessor, Janis Bobrin. “It was considered a mosquito-ridden swamp and not fit for habitation.”

After the War of 1812, Congress voted to give veterans two million acres in what was then the Michigan Territory. The plan was that the land, bought from the Huron River Potawatomi in 1807 for little more than a penny an acre, would reward the veterans for their service, while sales to other settlers would reduce the war-swollen federal deficit.

But in November 1815, U.S. surveyor general Edward Tiffin reported that his contractors had so much trouble traversing swamps and quaking bogs in what is now Jackson County that they “were obliged to suspend their operations until the country shall be sufficiently frozen so as to bear man and beast … The intermediate space between these swamps and lakes–which is probably near one-half of the country–is, with very few exceptions, a poor, barren, sandy land, on which scarcely any vegetation grows.” Concluding that not “more than one acre out of a hundred” could be cultivated, Tiffin recommended giving up on Michigan. The veterans got land in the Illinois and Missouri territories instead.

—

Michigan’s territorial governor, Lewis Cass objected that Tiffin “grossly misrepresented” the region’s potential. But with land access blocked by the Great Black Swamp in northwest Ohio, settlers didn’t reach Michigan in large numbers until the Erie Canal was completed in 1825, creating an all-water route across New York state and Lake Erie.

Ann Arbor’s founders were a little ahead of the curve: they hiked in from Detroit during a frozen January in 1824. They chose the future county seat for its “oak openings,” meadows above the Huron River valley that Native Americans had kept open by setting frequent grass fires. Life was harder for many later arrivals: the land they bought in the county had to be drained before it could be cultivated.

That was arduous work that required men with shovels–and later, horses pulling graders–to deepen existing creeks or dig new ditches to lower the water table. But “we all know that water doesn’t do anything in straight lines,” says Pratt. “You know, nature is all about wiggly stuff.” Because drains typically benefited multiple property owners, someone had to decide where to build them and who should pay for them.

That’s where drain (now water resources) commissioners come in. Their job is so important that townships had them even before Michigan became a state. “You needed to have somebody who would be in charge of the construction and operation,” explains Bobrin, “and then levy the costs of construction in an affordable manner on everybody who drains.”

A series of state drainage laws aided by the national Swamp Land Act of 1850 and the state’s consolidation of drain commissioners at the county level in 1897 allowed “people to band together [to build drains] and have some authority for them to pay over time,” says Pratt. “We have 720 miles of county drains, but they’re in 550 individual separate drainage districts.” The county sends out close to 30,000 tax bills for those drains annually, which bring in about $1.5 million a year for their maintenance.

—

According to the Michigan Farm Bureau, over half of Michigan’s farmland requires drainage. Using the county GIS mapping system, Bobrin says, you can see “where the most drains are, where there were the most wetlands, where the soil is the least permeable and drainage is critical. If you look at the southeast corner of the county [there’s] a heavy layout of county drains, and as you move northwest, there’s far fewer of them.”

Yet even there, the map is webbed with the dark blue lines of drains–the Mill Creek extension meeting the Mill Lake drain as it wraps around Chelsea, and the Mill Creek Consolidated drain picking up the Haas and Finkbeiner drains before entering Mill Creek itself. Around Saline, the Koch-Warner and Hertler-Nissley drains join several numbered Pittsfield drains in feeding the Saline River.

“Southeast Michigan [would] never have gotten settled without drainage,” Bobrin says. Even thoroughly urbanized Ann Arbor is undergirded with drains–‘including the now-buried Allen Creek and Malletts Creek. “They more or less laid the pipe in the bottom of the creek,” says Pratt, “and then they filled in the rest of the creek.” Water still rises out of those pipes in heavy rains. In older neighborhoods in southeast Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti last summer, a hundred-year storm flooded basements six feet deep.

Such heavy rains are supposed to have only a one-in-a-hundred chance of occurring in any given year. But a mentor warned him years ago, Pratt says, “there will always be a bigger storm”–and with climate change, they’re happening more often.

—

That’s why what settlers called swamps and drained are now called wetlands and protected from development: they slow and clean stormwater runoff and recharge groundwater aquifers.

A few of the area’s swamps survived the nineteenth-century draining onslaught. “The Liberty Road corridor west of Zeeb toward Parker is an example of a road running through a swampy area,” emails Bobrin. “The current drainage is still pretty inadequate”–as anyone driving there after a heavy rain knows.

But just as no one’s proposing to drain the last swamps, no one’s calling for restoring the old ones. Instead, the county engineers landscapes to do the work swamps once did.

Bobrin was the last person county voters elected as a “drain commissioner.” She explains that she orchestrated the change in her office’s title–which required a change in state law–because “preserving wetlands, we now know, is one of the most important things we can do for water quality and quantity management. ‘County drain commissioner’ connotes anything but that kind of stewardship of natural areas.”

Though Bobrin was the first to have an environmental title, she says, a predecessor, Tom Blessing, “was really the guy who started onsite stormwater management [locally]–like creating ponds on property when it was developed so that everything didn’t just run off onto the neighbors.” Blessing also “got some federal funds to construct different kinds of storage facilities and then monitor water quality to see how they were doing in terms of filtering out pollutants, when all of that was really cutting-edge.”

“Since the seventies, most of the urban drain commissioners have been focused on the water quality” rather than draining swamps, Pratt says. Most places now require onsite rainwater storage for new construction, though the state of the art has moved on from detention ponds to planted infiltration basins, better known as rain gardens. Pratt’s office creates them on public property and encourages property owners to build their own.

Some older subdivisions built before the standards went into effect, Pratt says, “have recurring flooding in their backyards, and people are mad all the time.” But even in last summer’s epic downpour, newer neighborhoods stayed dry.

—

Creating developments that coexist with nature is just one of the ways the office’s work has grown. “We have just a myriad of responsibilities: soil erosion control and new construction, go on down the list,” says Bobrin. “It’s about way more than drainage.”

When she was first elected in 1988, Bobrin was the only Democrat holding countywide office. Between her party and her gender, “I can’t say that I was greeted warmly by all the farmers,” she says. “But over the years we learned to work together.”

When she retired in 2012, she recruited Pratt to run for the job. She’d been impressed with him as a consulting engineer on several projects, liked that he understood development from chairing the Ann Arbor planning commission, and appreciated that “he grew up on a farm, so he even understood the agricultural aspect.”

“Washtenaw County has been fortunate that their agency has for decades now identified themselves as a water resource management agency,” says MSU geologist David Lusch. “In most of Michigan unfortunately it’s still called the drain commissioner, [and officials think] their prime function is to move water off the landscape as quickly as possible. From a hydrologic standpoint, that’s not necessarily a good thing.”

In their water-management efforts, the water resource commissioner’s thirty-four staff members are taking on work once performed by wildlife. In his 2018 book Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb explains that historically, beaver dams expanded wetlands and enhanced biodiversity. But in most of the U.S., trappers wiped out beaver populations even before settlers arrived, and while Goldfarb enthuses about the environmental benefits of bringing them back, he also recounts why that’s often controversial.

“Most people, unless they’re trying to promote some kind of a wilderness area, probably would view a beaver as a pest,” says MSU’s Lusch. “If you’re a farmer or a rural property owner and you’re being assessed hundreds of dollars per linear foot of county drain across your property, you’re going to view a beaver as the antithesis of what you’re paying for, because they’re going to hold the water on your land and make a pond.

“I don’t think the loss of beaver is a huge environmental issue per se,” he says. “The hydrology was doing fine with the beaver, and it’s doing pretty well without the beaver.

“Humans have a greater impact on the hydrology [with] impervious surfaces and more intense storms,” the geologist adds. “It’s we who are the greater pest on the landscape than the beaver.

“If we could be as good of hydraulic engineers as beaver, we’d be in much, much better shape.”

Could a Beaver Save Four Mile Lake?

“I would love to have a beaver,” says county water resources commissioner Evan Pratt. “He would solve all the problems!”

Located in the Chelsea State Game Area off Dexter-Chelsea Rd., Four Mile Lake is the county’s sixth-largest lake with a surface area of 256 acres. ‘Twenty-five years ago, it had a maximum depth of eighteen feet. Now it’s sixteen feet–and falling. As the water retreats, a public boat-launch ramp now ends well short of the water.

The lake is next to what was once an open-pit mine, and “at some point in time, they built an embankment or a berm for about a third of a mile on the western side of this lake,” Pratt explains. But “the water [found] a path of least resistance, and it’s been cutting a hole through this berm” and into the former mine.

About twenty years ago, a permit from the state allowed the county to sandbag the hole, but the barrier quickly washed out. These days, “the state’s not too keen on issuing permits,” Pratt says, and the cost of a permanent solution is likely beyond the means of the few property owners on the lake.

“Beaver dams would do a better job than sandbags,” he says. “If we had a beaver that would absolutely address the whole situation.” But Michigan’s DNR still treats the animals as pests, not environmental allies, and Pratt himself admits that in the wrong place, they’d do more harm than good.

But at Four Mile Lake, he wishes they were an option, because a human-built dam would be so expensive.

“Just the construction piece is at least $4 million,” he says. Beavers, of course, work for free.