In the spring of 1989, a drama fraught with irony began playing out in Austria. A Jewish American family, a mother and her two grown sons, were fighting extradition to the U.S. About fifty years before, Jewish families were desperately trying to leave Austria for safe havens like the U.S.

The subjects of the extradition were Linda Leary and sons, Paul and Richard Heilbrunn. They fled to Austria in anticipation of a federal grand jury indictment in November 1987. The indictment ran 136 pages and contained fifty-three counts charging thirty-four people.

Paul and Richard were charged with running a massive marijuana smuggling and distribution operation, legally termed a Continuing Criminal Enterprise (CCE). According to the indictment, the ring operated from 1975 to 1985, distributed more than 150,000 pounds of weed, and took in more than $50 million in cash. The figures were subsequently revised upward to 250,000 pounds and $50 to $100 million. It would prove to be the biggest marijuana ring ever prosecuted by the U.S.

—

Today, with many states legalizing marijuana, looking back on the investigation is almost like looking back on Prohibition. Like the bootleggers of the 1920s, the Heilbrunns and their cohorts weren’t protesting the illegality of their product; they were taking advantage of a restricted market. They could set the price: they had little competition, and the profits were tax free.

Paul Heilbrunn was characterized as the ringleader. Testimony depicted him as both respected and feared–he was referred to as melech, Hebrew for king. Prior to the indictment, he was posing as a successful commodities trader in Indianapolis, even writing a column on the subject for the local newspaper. But the main commodity he traded was marijuana. Most of it came by ship from Colombia, Jamaica, and Thailand; it was then trucked to Indiana and stored in barns owned or rented by the Heilbrunn organization.

The beginning of the end for the drug empire came with a cocaine dealer’s arrest in 1983. The dealer had previously worked for the Heilbrunns but had been let go, ironically, for his own drug use. He offered to tell what he knew about the operation as part of a plea bargain. There is no honor among thieves, and little to none among drug dealers.

Law enforcement meticulously put together a case that culminated in the 1987 indictment. Most of the people charged were known to the federal grand jury, but three Michigan residents were identified only by aliases: a man referred to as “John Doe, also known as the Joker,” and his two female subordinates, named as Jane Does, aka “Tipper and Topper.”

While the Heilbrunns were fighting extradition, most of the indictees were prosecuted and convicted. Some cooperated and agreed to testify against others, including the Heilbrunns. At one of the co-conspirators’ trials, the Joker was depicted as “Paul Heilbrunn’s trusted and valued peer.” But no one seemed to know the Joker’s true identity.

One person in the Joker’s Michigan organization had been identified and prosecuted: James Shedd, who had stored a 40,000-pound load of Heilbrunn marijuana in a barn he owned in Ypsilanti Township. (Shedd had also previously been the manager of Ypsilanti’s Sidetrack Bar & Grill.) But Shedd had refused a plea deal and would not identify the Joker. I suspected that stand may have been based more on compensation from the Joker than on honor.

It became a personal challenge for me to identify the Joker, a matter of pride. The Joker was a huge marijuana dealer who had been operating in my territory with impunity.

I learned of someone who might know who the Joker was and contacted him. Over several months we periodically met for coffee. We talked about a lot of things: sports, politics, and–although nothing specific was discussed–drugs. Slowly I gained his trust. I told him I would never disclose his identity, and that any information he provided would be reported in such a way as to keep him anonymous. At no time did we discuss any compensation. We both understood if he talked it would be because it was the right thing to do.

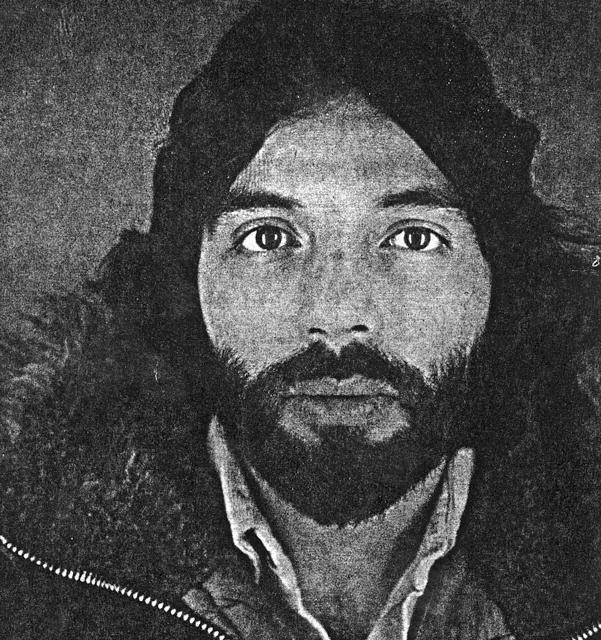

We began to discuss marijuana distribution in Michigan. In early 1989, I asked him if he could help me identify the Joker. His said yes–in fact, he could tell me who the Joker was: he was James Hill.

James F. Hill owned a house in Burns Park and an ice cream shop on Main St., the Lovin’ Spoonful. He also owned and lived on an eighty-acre farm just west of Ann Arbor. Hill had a master’s degree from the University of Chicago, and his only criminal record was a minor traffic violation in 1973.

I sent a copy of the arrest photo to Indianapolis. After seeing it, several of the cooperating witnesses identified James Hill as the Joker.

—

The Indianapolis office obtained an arrest warrant for Hill, and we set up an arrest team at Hill’s farm. When he was leaving the farm, we arrested him and took him to the Ann Arbor FBI office. I explained to Hill that he had been identified as the Joker in a federal indictment from Indiana charging him with multiple drug trafficking violations, and that he would be taken to Detroit to be arraigned. He would likely remain in custody until he was transported to Indianapolis.

He seemed to have expected to be arrested. He indicated he would be cooperative, but he didn’t want to be interviewed until he got to Indianapolis.

When the media learned of Hill’s arrest at the arraignment, they wanted to know how he had been identified. Rather than say nothing and encourage speculation, I made a statement that one of the cooperating witnesses in Indiana had identified him, which was partially true.

Hill was removed to Indiana and did cooperate. Tipper and Topper were identified as sisters Jennifer and Patricia Hanlon. They later pleaded guilty and were each sentenced to six years.

In late 1989, the Heilbrunns lost their two-year fight against extradition and were returned to the U.S.

—

In October 1990, Hill pleaded guilty and agreed to testify against the Heilbrunns. In his plea agreement, Hill admitted to having received several shipments of 1,200 to 2,000 pounds of marijuana, starting in 1976. Then, between March and November 1985, Hill received marijuana shipments totaling 82,000 pounds. Hill said he made his last payment in 1986. By then he had paid the Heilbrunn organization about $20 million for more than 100,000 pounds of marijuana.

James Hill was sentenced to twenty years. Because he had pleaded to having run a Continuing Criminal Enterprise, all of his assets were subject to forfeiture. The U.S. District Court judge said that Hill would have received harsher punishment if not for his cooperation.

In January 1991, Linda Leary also pleaded guilty and agreed to testify against her sons. She was subsequently sentenced to nine years.

There was no trial of the Heilbrunns. Paul and Richard pleaded guilty in April, and in July 1991 they were sentenced. Richard got thirteen years. Paul, the King, received twenty-eight years.

To my knowledge no one ever learned the identity of the source who identified the Joker. —

A version of this article previously appeared on ticklethewire.com. Greg Stejskal served as an FBI agent for thirty-one years and retired as resident agent in charge of the Ann Arbor office.