Jason and Julia Gold started the folk school to preserve traditional crafts. Credit: J. Adrian Wylie

In 1973, the nascent Washtenaw County Parks and Recreation Commission had a handful of roadside picnic parks and big dreams. Early champions, including county commissioner Meri Lou Murray, had made it a self-governing commission rather than a department of county government in order to give it greater autonomy. This relative independence has allowed WCPARC to do things few parks departments can, including propose millages, own land, and forge innovative

partnerships with nonprofit and local government groups.

Fifty years later, partnerships have helped create more than forty miles of the B2B border-to-border trail; thirty-five nature preserves; fourteen parks; and 12,000 acres of conservation easements.

Now the parks commission is embarking on its most ambitious partnership yet: It’s transforming the ninety-eight-acre Staebler Farm into an agriculture-themed park—and has acquired the nonprofit Michigan Folk School to teach classes in traditional skills like those practiced on a centennial farm.

The origins of Staebler Farm Park date back decades, to a series of conversations between Don Staebler, a cattle farmer on Plymouth Rd. in Superior Township, and his neighbor Fred Barkley, WCPARC’s director at the time.

To the Staebler family, traditional crafts were a way of life. Credit: courtesy WCPARC

“Don definitely had a vision, and he wanted his property preserved as a farm,” explains former superintendent of park planning Tom Freeman, who knew both men. “He had resisted a lot of pressure from developers to turn it into housing. He and Fred came up with the idea of turning it into a park.”

Staebler moved to what was then a dairy farm with his parents in 1912 when he was two years old, but it had existed in some form since 1826, when settler Justin Phelps purchased the land from the federal government. The area’s last Native American inhabitants, the Wyandot and Potawatomi, had ceded the land in the Treaty of Detroit in 1807.

Plymouth Rd., which bisects the farm, was a Native trail stretching between Ann Arbor and Detroit. Frain’s Lake and Murray’s Lake, which border the property on the south, were connected. Analysis of tools, arrowheads, and pottery fragments suggests the shoreline had been a summer campground for migrating tribes for more than 8,000 years. But along with other tribes east of the Mississippi, the Wyandot and Potawatomi were forcibly removed to Kansas in the 1830s and 1840s, leaving only a small presence in southeast and west Michigan.

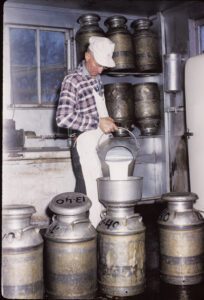

Don Staebler (collecting milk in the 1950s) told his neighbor Fred Barkley that after his death he wanted the property preserved as a farm. Credit: courtesy WCPARC

Staebler grew up doing farm work, but his parents made sure he and his siblings were well educated. In addition to helping on the farm, Staebler was a high school headmaster, taught industrial arts during the Depression, worked as an instructor at Ford’s Willow Run bomber plant in WWII, and invented a trailer brake system that he patented.

Staebler and his wife, Lena, purchased the farm from his mother in 1952 and transitioned from dairy to cattle several years later. “He didn’t think people understood that a farmer is more than a guy who gets up in the morning and milks cows,” says Freeman. Staebler hoped that as a park, the farm would remain active and be a place of learning.

“Operating the farm and having it there is one thing,” says Freeman, “but bringing the public to that property and having them learn about traditional skills that people used to do as a part of farming, that’s the thing that counts.” Freeman jokes that while WCPARC is highly capable, there are limits. “Blacksmithing? Not something they’re good at.”

The commission purchased the farm in 2001. Staebler was ninety, and the purchase came with the stipulation that he be allowed to live on the property for the remainder of his life. Adding an adjacent parcel purchased from the Vera Heidt Trust increased the park site to ninety-eight acres.

Work began immediately on a detailed master plan of the farm, including an inventory of flora, fauna, and Staebler family history. Park planner Kira Macyda was the lead researcher and wrote the plan. She, Freeman, and other park planners reached out to the community for feedback, brainstormed ideas with township officials and local nonprofits, and visited other agriculture-themed parks, including Kensington Metropark. They had plenty of time to refine their plans: Staebler lived another sixteen years!

“The vision for the site said that the park would celebrate agricultural heritage and offer the opportunity for amazing programming,” says Macyda. “As we develop signage or potential exhibits in the future, the Staebler family will be highlighted in the broader context of Washtenaw County heritage, as a way for people to relate.”

WCPARC planner Kira Macyda with the restored Staebler barn. “We wanted the agricultural component without being a kitschy farm-themed park,” she says. Credit: J. Adrian Wylie

They understood that balancing the needs of an active farm while providing educational opportunities and recreation for the public could be tricky and expensive. “We wanted the agricultural component without being a kitschy farm-themed park,” says Macyda, adding that Kensington Metropark administrators told them that the park loses money. And while managing a farm and educational programs was beyond the commission’s capabilities, “if we have a partner we can charge for programming.” Finding such a partner was the challenge.

The answer came when Freeman met Jason Gold through their mutual involvement with the Dixboro Farmers Market. Gold and his wife Julia ran the Michigan Folk School, a nonprofit they founded that taught everything from shoemaking and metalsmithing to broom making and gardening.

Freeman thought it could be a natural fit for Staebler Farm. “The folk school model that was described to me by Jason was one that can bring in all these diverse skills and let the community come see and try this stuff, and do it in a way that doesn’t bankrupt the organization,” he says. “Then Jason scared the heck out of me.” He and Julia were looking for a permanent home for the folk school and were thinking of moving out of the area. Freeman connected Gold to county parks superintendent Ginny Leikham.

“So Ginny and I met on a park bench in May of 2016, and she told me all about Staebler and I told her all about the folk school,” says Gold. He and Julia had first learned about the concept during a summer break from college in 1998, when they visited the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, NC. They were instantly smitten. “It was summer camp for adults!” he gushes. The couple returned every summer to take classes. Folk schools, he says, “developed in Northern Europe 200 years ago when there was a real fear of people losing knowledge with the advance of industrialization.

“But this is not Greenfield Village, and we don’t wear costumes,” he adds. “While we are doing crafts that are hundreds, sometimes thousands of years old, we are still using modern technology.” In 2012, the Golds started an itinerant folk school as a side project from their teaching jobs.

Gold with park coordinator and blacksmith instructor Wade Buck. The folk school officially joined the county park system in January, with Gold as both school director and manager of Staebler Farm Park. Credit: J. Adrian Wylie

Leikham and Gold drove together to Staebler Farm Park to look around. As they walked the property, Leikham explained that Plymouth Rd. would be a natural dividing line between the park’s planned activities. Active recreation would be on the north side of the road and would likely include exploration of Fleming Creek, a picnic pavilion, fruit trees, a playground, fishing, and walking trails through a nature preserve.

M-14 runs along the northern edge of the property, and the builders had left two borrow pits where gravel was mined for its construction. WCPARC would turn them into Peaceful Pond and Heidt Pond and stock them with fish. Pasture, a well house, silo, pig house, and three

nineteenth-century barns are also on the north side. Sheep, goats, and other small animals will graze and sleep in the barns, one of which has been beautifully restored. More restorations are planned for the other buildings.

Passive recreation south of Plymouth Rd. would include walking trails around hayfields and noncommercial agriculture. Don Staebler’s workshop would house a partner organization’s educational programming. “We realized that there’s a lot of synergy here,” Gold recalls. “We were excited about what the possibilities could be.”

Leikham emails that “The Folk School provided programming that was not being offered by County Parks at the time, had a track record of successfully offering classes, and a connection to the cultural arts and crafts community, so we started the conversation about how both of our missions and vision for Staebler Farm overlapped.” In 2017, they invited local organizations to submit proposals for using the property, and the Michigan Folk School was selected.

Gold describes walking into the workshop for the first time as an “Oh my!” moment: It needed to be fully renovated before classes could begin. WCPARC took responsibility for renovating the nineteenth-century farmhouse and chicken coop, but the folk school would have to fix up the workshop and add a blacksmithing studio.

He hoped to raise $80,000, but enthusiasm was so great they quickly raised $120,000. The folk school opened its doors in February 2020 and ran for a month before Covid hit. After closing for a few weeks, Gold decided to reopen and continued to operate in person throughout the pandemic. Classes were booked solid.

The only problem was a lack of space. “In order for a folk school to become a sustainable entity, you need enough classrooms to be able to pay for the administration,” he explains. In the school’s second year, Gold and park planners began to discuss the possibility of building a multipurpose center on the south side of the park that would house classes, including culinary arts. They also began to explore what it would look like if the parks commission took over the nonprofit.

Gold and his board of directors would have to give the school to the commission, and he would have to apply for the job of school director and park manager alongside other qualified candidates. It was a risk. But without enough space and resources, running it was becoming onerous. So last November, the Michigan Folk School board voted to be acquired by WCPARC. It would become the only example of a parks commission running a folk school in the U.S.

On January 1, the folk school officially joined the county park system, and Gold was hired as its director and manager of Staebler Farm Park. The school’s nonprofit entity was renamed the Friends of the Michigan Folk School, which will make it easier to raise funds to expand beyond what class revenue and WCPARC can cover. An advisory group of instructors, crafters, government representatives, and residents cocreate its evolving vision.

And what does that vision entail? “I want a Tom Sawyer/Huck Finn boat. One of those rafts that you pull the rope to bring the raft across the pond. I want one of those!” laughs Gold. But before that can happen, they will finish construction of the multipurpose building, renovate the farmhouse and the other outbuildings, introduce animals, build a picnic pavilion and trails, plant trees, and restore Fleming Creek.

Once that’s done, Gold hopes to plant seasonal crops in the gardens and fields on the south side for use in artisanal cooking classes. For example, they might grow wheat to grind for making bread.

Gold says he wants to make the park “a place where people can come and self-heal, whether that’s taking a class or maybe it’s working in the garden.

“My official title is park manager that officiates everything, but to be quite honest, I think of myself more as a concierge. It’s not about what I want for the school and what I want to see. You got ideas? Sit down, let’s talk.

“Granted, I do want the Huck Finn boat! But I just wanted to be a part of it, and that has allowed me to meet some of the most amazing people I’ve ever had the chance to work with.”