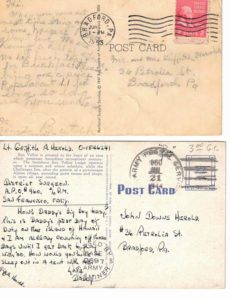

It was 1944, and my father had just arrived for Army duty in Hawaii. An attorney by trade, he was assigned to a medical unit administration. He penned a postcard to me, then just three years old.

This is Daddy’s first day of duty on the island of Hawaii and I am already counting off those days until I get back to play with ’oo. How would you like to sleep out in a tent with me?

I’m almost eighty-two now, and my memory of life at that age is long gone. There are photos of me in a replica of my father’s Army uniform that my mother had made, but I don’t have any recollections of the postcard’s arrival.

But life is funny, and through a strange twist of events, I got a chance to relive this moment—seventy-eight years later.

Nowadays, we receive social media notifications with pictures and messages from friends or family wherever they are … which might even be on the other side of the room. But before the addition of cameras to cell phones, postcards were a way for people to share their travels with their friends and family back home.

Life is funny, and through a strange twist of events, old postcards sent by strangers gave me a chance to relive moments in my past.

By the time my father sent that postcard from Hawaii, the “golden age” of postcards had already come and gone. Two postal innovations at the end of the nineteenth century—lower rates for cards and rural free delivery—made sending and collecting picture postcards a veritable craze in the United States: By 1913, Americans sent and received nearly a billion of them. But a tariff squelched the import of German-manufactured postcards, and American companies’ printing technology just wasn’t up to the same standards. The number of postcards sent wouldn’t approach a billion again until 1950.

By the time I made my first trip around Europe in 1962, postcards were used the way folks use Facebook today—shorter than a letter and cheaper to send, but still a good way to check in with friends and share (or show off) your travels.

I had an Ann Arbor–made Argus C3 camera, expensive slide film, and a budget of $8 a day. In an effort to get good photos and save money, I checked out local displays of picture postcards for sale and made mental notes of locations and angles. I can remember buying postage in American Express offices in Berlin, Rome, and Paris that were full of Americans picking up personal mail and sending off postcards that family members could show around back home.

Postcards haven’t quite gone the way of the dinosaur, but the numbers have been consistently dropping—so much so that the U.S. Postal Service tracks postcards and stamped cards as one category. 2021 saw the delivery of 435 million cards and postcards and more than two billion presorted postcards—that is, marketing materials destined for the trash.

But there’s a community keeping the tradition of postcard collection alive: They’re known as deltiologists. Many of them display their collections on personal websites, and there are dozens of shows nationwide for people to meet and deal postcards.

The U-M’s Clements Library has its own impressive collection: The David V. Tinder photo postcard collection consists of more than 60,000 postcards dated from 1906 through the 1950s. Each one is a window into Michigan’s history.

In 2022, master’s degree student Claire Danna scanned the postcards as part of her assistantship with the Clements Library. Now they’re using Zooniverse, an online platform for crowdsourced research, to solicit help identifying and classifying the postcards. When the project is completed, anyone anywhere will be able to search the collection.

It seems that even though social media may have mortally wounded the picture postcard industry, technology is also giving it new life. And that’s where an old postcard from my childhood came back into my life.

I checked my email one day in 2021 and found a message from a deltiologist who collects cards from our hometown of Bradford, Pennsylvania. He found my email through a website I built for my Bradford High School class (1959), he said, and asked if I might be interested in a postcard he’d found.

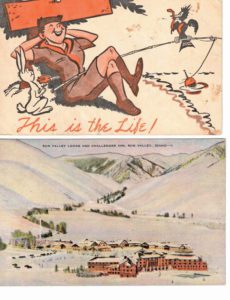

The almost seventy-year-old postcard features a drawing of a Boy Scout relaxing with a fishing pole in his lap, above the words “This is the Life!” It was addressed to my parents and postmarked July 21, 1953—in case you’re wondering, postage back then was two cents—and written in the careful cursive of a twelve-year-old:

“We are having a hell of a time. We had french toast for breakfast,” it reads.

That’s right—I’ve received not one, but two postcards from my past.

How did this card happen to become available to the world of postcard collectors? My best theory is that my mother must have added the card to her family postcard collection. When she moved to Florida following my father’s death, she probably passed the collection to a family friend, himself an avid collector of precanceled U.S. stamps. In closing his estate, that collection may have been included in an estate sale. From there, who knows where else that postcard traveled before it made its way back to me?

Being reunited with a small relic of Boy Scout camp was an unexpected delight. But imagine my astonishment when I received a message from another postcard collector later that same year.

This deltiologist had purchased his card in a used bookstore in Salt Lake City and knew immediately that he wanted to get it back to its original owner. He tracked me down with an internet search, finding my contact information on the Ann Arbor Rotary Club website, and soon the postcard was back in my hands. The picture is of a hand-painted winter scene from Sun Valley Lodge and Challenger Inn in Idaho, but the message is from Hawaii.

Holding my father’s postcard in my hands brought that period of my life into sharp focus. It gave me a new insight into what he was thinking just after being stationed so far from his family. I recalled my mother’s war-related activity—she was a member of the “Motor Corps” in our hometown of 15,000—and seeing photos of her in uniform.

The postcard was accompanied by a note (handwritten, of course), from the collector:

“I’m not sure what it is about old postcards that I am so drawn to,” it reads. “I love the art, but I also love the idea of someone who is visiting somewhere new, but wanting to send love to those who are not physically with them. Usually the cards I find are not from a father to son during a war, but I think that this card only highlights the love written into a 4×6 piece of paper. It’s important to be reminded of how much love there is in the world, especially when things feel so dark and we are so isolated from those who are most important to us.”