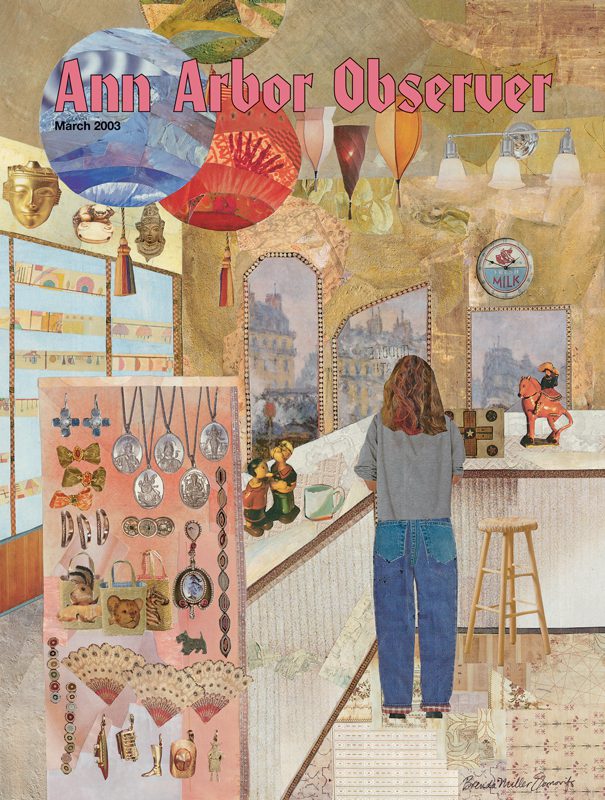

A 2003 Observer cover by Brenda Miller Slomovits inspired by Middle Earth. | Illustration by Brenda Miller Slomovits

One Saturday in May 1971, I was a sixth grader on a mission: I wanted to buy a silver peace sign necklace. At the store Middle Earth on South University, in the heart of the campus, I looked carefully at the young woman with wire-rimmed glasses behind the counter. She had frizzy hair, a macramé belt, large hoop earrings, and a choker-style necklace. She looked a little like Janis Joplin and was wearing a T-shirt with the word REVOLT and a picture of a clenched fist. This young woman looked like she would be just the right person to help me.

Middle Earth had a significant amount of drug paraphernalia, as well as political buttons, books, beads, cards, candles, jewelry, and everything a countercultural student would want. The smell of the incense made my head pound, but I liked to look at the large selection of black light posters.

I was looking at a picture of Janis Joplin near the counter, and the woman asked me if I knew who this was. “Of course,” I said. “Everyone does. She died last year.” The woman said she had heard Joplin two years earlier when she came to Ann Arbor.

“Did she play ‘Piece of My Heart?’” I asked. She said no and wondered how I knew the song and whether I knew that Joplin went by the nickname Pearl. I nodded. “A person over at Discount Records told me about both,” I explained.

They had a lot of peace sign necklaces, so she had many questions for me. No, it was not for my sister, I told her. It was for a classmate who sat next to me in the back of the class. It was a graduation present—we would be going to different junior high schools in the fall. She asked what sort of statement I wanted to make. I said I just thought she would like it.

She pressed me on a number of things that I felt were personal but for some reason I didn’t mind telling her. She then repeated back what I had said to her in an official sounding way: “So, you’re in sixth grade. You pass notes to each other in the back row of class. Right. And talk to each other sometimes about math. She is very tall. All right. She laughed at some con you played on a substitute teacher last week. And she likes your silver peace sign ring that you got in Mexico.

“Hell yes, makes perfect sense to me about getting her this necklace then,” she concluded. And when she summarized it like this, with a swear word thrown in, it was clear to me that I was doing the right thing.

After I looked very carefully at the selections, I asked the woman to pick out a necklace that she thought would be best. I told her I had the money because I had four jobs. She found exactly the one that fit the situation. She provided a psychedelic box for it.

She said that she would give me a partial discount, for a good cause.

Riding home on my bicycle, I debated whether to show it to my mom. I decided that she would think it was a nice gesture, so I did. My mother examined it closely, looked at the price tag, and immediately expressed concern that it was too extravagant a gift to give a girl in the sixth grade. She patiently explained that this was something you would give someone as a gift when you were a lot older. And, having been born in the Depression, my mom just shook her head at the price.

Less patiently, I explained that this was my money, and I could do whatever I wanted with it. Hard-earned money, I reminded her: paper route, lawn-mowing business, snow shoveling, and janitorial work at the campus chapel nearby where my father was the minister. And then—what I thought would be the clincher—I told her about the discounted price. My mom remained resolute.

She recommended that I go back to the store and “reconsider things.” So, to appease my mom, I went back to Middle Earth and got a much cheaper but still cool black light poster. I saw the young saleswoman and told her I was going to give my classmate the poster. I told her what had happened with my mom and what I planned to do about it. She looked at me and smiled. “Subversive,” she said. “You have to do what you have to do,” she added, the clenched fist on her shirt giving her an air of authority.

As I was leaving, she casually asked whether I was considering stealing the book placed by the door. It was the student radical Abbie Hoffman’s new book, famously titled Steal This Book. She said she didn’t care if I did—the store had budgeted for thefts.

I was already planning to engage in an act of omission when I got home, but a sin of commission, the theft of a book, was a little too much for me in one afternoon. I told her that I wouldn’t want to steal a book that I didn’t have time to read. And it was true that I had limited time. Sixth grade and my jobs were proving to be a lot of work.

“Peace,” she said as I walked out of the incense of Middle Earth into the fresh air.

When I showed the black light poster to my mom, my brother laughed because the whole purpose of a black light poster was to use it with a black light. “Do you know if she even has a black light?” he asked. I had to admit that I hadn’t considered this.

My mom thought it was an appropriate gift. But importantly, she never asked about the necklace.

And it was still in the box in my pocket.

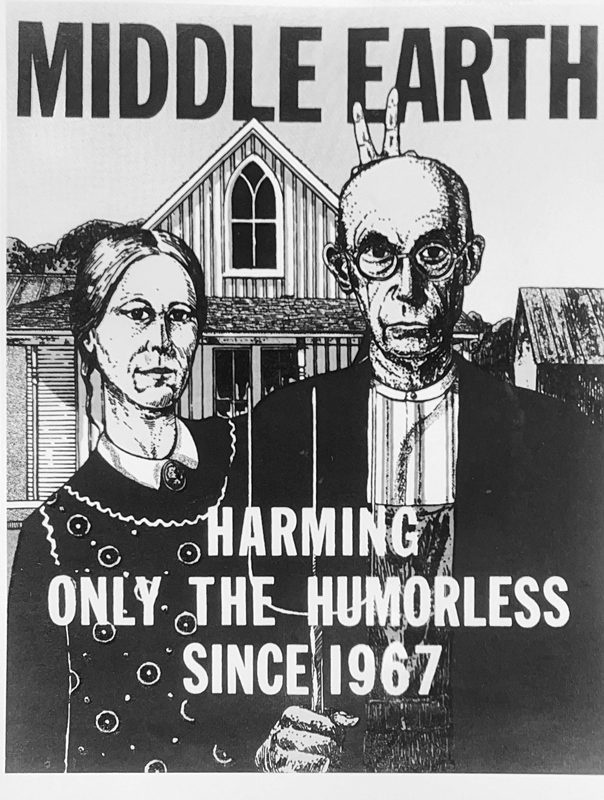

An icon adapted to promote the store’s slogan. | Courtesy of Middle Earth

The lesson I learned that day was that it was important, at times, to provide only a certain amount of information to my parents. Limited information was really in their best interest, I reasoned. I also reminded myself that my mom had told me several times before that “Sometimes it is best to say nothing at all.” I thought this was definitely one of those times.

Finally, I rationalized, my mom had only asked me to “reconsider things.” I had certainly done that: Upon reconsideration in Middle Earth that afternoon, I thought it best to let my mom feel good about the black light poster gift and her parental advice. And on further reconsideration, it was equally important to not have her worry about the necklace any longer. And, in any event, I had other things to plan for.

My parents let me invite six friends to a postponed birthday party/graduation party at Bimbo’s pizza parlor downtown. A popular spot that had a Dixieland band, shelled peanuts, and unlimited amounts of Faygo Redpop, Bimbo’s was perhaps the furthest thing conceptually from Middle Earth in Ann Arbor. I invited five of my longtime friends and the classmate to whom I had given both the black light poster and peace sign necklace.

I was drinking Redpop when she strolled into Bimbo’s wearing a white dress and a red bow. When I saw she was wearing the necklace, I snorted Redpop through my nose. As I was trying to control this unsightly mess, I stood up and started to slip on the peanut shells on the floor. I gripped the edge of the table that also had peanut shell residue to steady myself. While trying to wipe the nasal liquid off my best shirt, I waved to her with a hand that was now covered with sticky red-peanut residue.

Future city attorney Stephen Postema as a sixth grader. His quest for a gift for a classmate led him to the city’s quintessential counterculture emporium. | Photo courtesy of Stephen Postema

The girl came over to sit between me and my mom. When she saw my hand up, she moved even closer to my mom. I was trying to whisper to warn her to not tell my mom that I had given the necklace to her. But with the Dixieland band playing loudly, she evidently thought I had asked her to do the opposite. So I heard her telling my mom all about the necklace and the black light poster. They just chatted away in detail about it as we ate pizza.

After the party, and after dropping the girl and another friend off, I waited for my mom to say something all the long way home in the car. Nothing all the way down Main St. to unlit Scio Church to home. At home, I looked right at her and thanked her for the party. She smiled and said she enjoyed talking with my friends. She said nothing about the necklace or the act of omission I had committed. For my twelfth birthday, my mom had let it slide.

Just let it slide.

The next time I was in Middle Earth I told the young woman about my party, the Redpop, my hand, the girl walking in with her necklace, and my mom’s grace. She laughed. “Crazy,” she said. And she pointed at the picture of Janis Joplin on the counter, touched me on the arm, and laughingly proclaimed: “I’m telling you—Pearl would have gotten a real kick out of all this.”

This essay is drawn from Postema’s forthcoming collection, Running Around Town.

I just went through a black hole time warp back to my 6th grade Ann Arbor self. I was at Angel School so South U was a regular after school pedestrian haunt. Middle Earth was so forbidden for me and all my friends that of course it was one of my favorite destinations after stocking up on grape gumballs at Strickland’s. I remember vividly the birthday parties at Bimbos, the smell of the peanut shells and their crackling underfoot. Thank you for this.