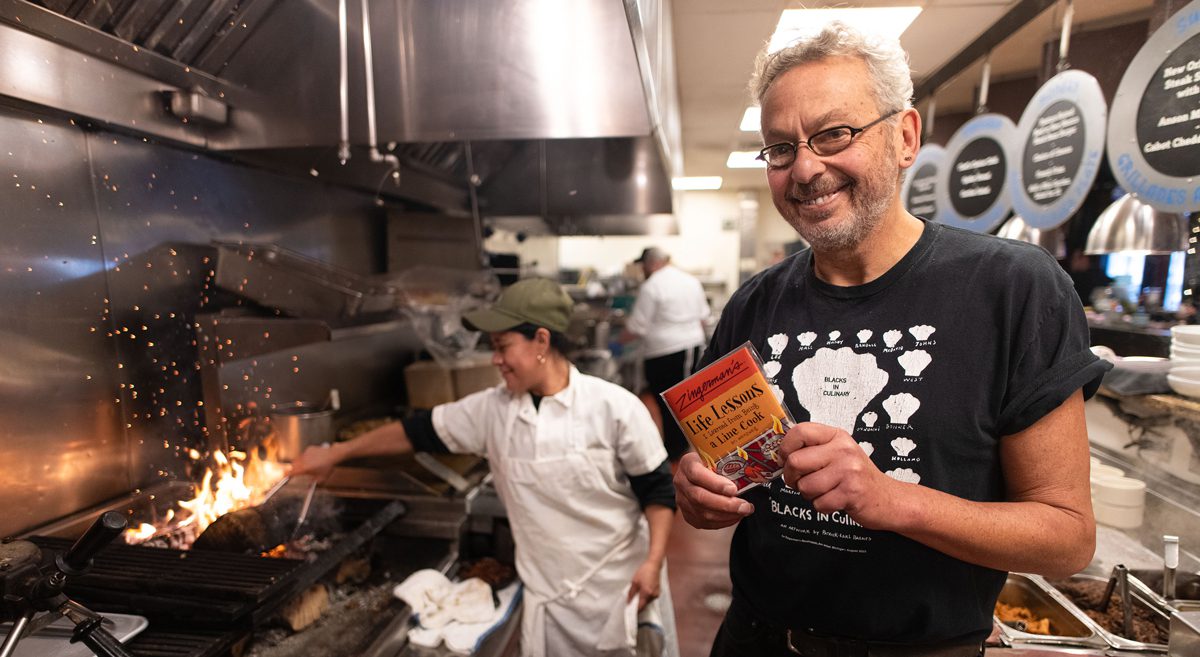

Weinzweig with his book and a working line cook at Zingerman’s Roadhouse. When people asked him what it feels like to be a successful entrepreneur, he writes, he fumbled for an answer until “I realized I could just tell the truth: ‘I feel like a line cook who’s doing pretty well.’” | Photo by Mark Bialek

Ari Weinzweig and Paul Saginaw opened Zingerman’s Delicatessen in 1982. It became the cornerstone of a Community of Businesses that today has a staff of 700 and annual sales of more than $80,000,000.

Along the way, Weinzweig has published more than two dozen books on food, business, and leadership. This article is excerpted from his latest, a hand-bound chapbook that connects his early life to his work today.

Every once in a while, it happens…

In the middle of a conversation about the struggles of leadership or the challenges of running a small business, a curious person will shift gears and ask me something along the lines of “How does it feel to be such a successful entrepreneur?” I usually smile and deflect the compliment with a bit of heartfelt humility: “Thank you. You’re very kind.”

Time and mental space allowing, though, I might answer the question in a bit more depth: “To be honest, I don’t really think of myself as either a ‘success’ or an ‘entrepreneur.’” The typical response is something akin to, “Really? Then how do you see yourself?”

For years, I fumbled around for an answer. Eventually, I realized I could just tell the truth: “I feel like a line cook who’s doing pretty well.”

There is nothing I can recall from the early years of my existence in suburban Chicago that would have led me—or anyone else, for that matter—to believe that my life story would later be transformed by a deep connection to food and cooking.

Our family’s eating routines were pretty pedestrian and most of our meals were rather mundane. The beauty and joy I experience today with cooking and eating were largely absent. We certainly ate supper together more often than not, but food was hardly at the center of my family’s story. Granted, my grandmother came over on Friday nights to cook the weekly Shabbos meal (roast chicken, chopped liver, chicken soup, and potato kugel), but it was really just a sidebar to a host of other “more important” topics of conversation.

Most of the foods I grew up with were actually the antithesis of what we do here at Zingerman’s. They were products of industrialization that came out of the twentieth-century shift from farmers markets to the mass market. As I share in the pamphlet “A Taste of Zingerman’s Food Philosophy,” the Pop-Tarts®, Tang®, Twinkies®, Fritos®, Cheetos®, Kraft® Mac & Cheese, Mrs. Paul’s® Fish Sticks—and a host of other items that all require registered trademarks to be used alongside their names—kept me fed and made me happy, but they didn’t inspire any big life plans.

At the time I started my undergraduate studies at the University of Michigan, I really had no clue what I was going to do when I “grew up.” I was “supposed” to go somewhere for further education—like maybe law school, med school, or some yet-to-be-determined degree at graduate school. There was certainly no version of my life story circulating when I was seventeen that had anything at all to do with farmhouse cheddar, first flush Darjeeling tea, or the fresh milling of organic grain. Where I came from—literally and conversationally—none of these were ever on the table. I doubt that I, or anyone I knew, had even heard of them.

Related: Anarchist Press

To be clear, when I took my first job washing dishes, I had absolutely no inspiring life ambition, nor any hint of a strategic plan to shoot me forward toward “success.” It was really just a coincidence that one of my college roommates happened to be working at Maude’s restaurant downtown and seemed to sort of like what he was doing—at least he’d made enough positive comments about his job that joining him there sounded like a reasonable short-term option for me. At the time, my interest was mostly just to avoid getting sucked back into life in the Chicago suburbs. Without any big plans, I decided to simply stay put in Ann Arbor.

In that sense, it was luck that I came into cooking for a living, but I know enough to know that there’s more to the story than just good fortune. Doors open, yet most of us find a wealth of reasons not to walk through them. I could easily have fallen into the unhealthy version of the food business that’s gotten so much bad press over the years. Or I could have just quietly kept my head down, stayed in restaurants for a year or so, and then gone to grad school like my mom wanted me to. Certainly, I had any number of advantages that my middle-class, learning-focused Jewish family afforded me. Still, as neuroscientist, psychologist, and author Angela Duckworth writes, “Our potential is one thing. What we do with it is quite another.”

For me, all this calls up the saying, “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.” Looking back, it’s reasonably safe to say that I was ready to learn a lot from food and cooking, and to let those lessons change my life for the better as they continue to do today. When the managers at Maude’s offered me a job washing dishes, I got right to work. A few months later, I started learning how to prep, and from there I moved up to cooking the line.

I learned early on that to get dinner for six out to a table successfully requires an amazing amount of things to go as they should and dozens of people (including me) to do our jobs well. To time all six main courses, appetizers, drinks, and desserts (each coming from different stations) so they show up at the right time; for the host to greet with great energy; the bartender to garnish every cocktail precisely; the folks preparing the food to season each dish correctly; and the food runner to carry the plates properly… if all of that happens as it should, it’s almost a miracle. And that doesn’t even account for the work of the baker, the brewer, the farmer, and the fisherperson without whom we wouldn’t even exist.

Growing up in a big city at the height of the industrial era, in a family that spent much more time and energy engaged in intellectual debate than they did walking in the woods, I was pretty well cut off from the wonders of nature. For me, seasons were mostly about transitions—from sun to snow, baseball to basketball, summer vacation to the start of the new semester at school. As a kid, I had no clue that strawberries were only available for three weeks in the spring, fresh milk was once seasonal, or that there is a particular time of year when olive oil is pressed.

At some subconscious level, I probably craved that connection. All these years later, I can see that I successfully traded the concrete and asphalt I was so comfortable with growing up for cooking, and endless intellectual debate for ever-increasing culinary insight.

Working with food taught me to really taste, touch, smell, and savor. It helped me learn how to listen better to my body, to watch the way birds land on branches, to take in the grace of the bees as they buzz around colorful blossoms. Working with food in this way opened a whole new world for me.

As Stephen Harrod Buhner says, “If you pay close attention, you will notice there is a difference. There is a livingness to it, which the pen or cup or desk did not have (or perhaps did not have as much). And that livingness has a particular feeling to it.” If you stick with it, Buhner says, “you begin to encounter the living reality.” Line cooking helped make that happen for me. My life is radically richer because of it.

Related: Iconic Restaurants of Ann Arbor

Working with food also has taught me time and time again how small a presence each of us are in the world. As business writer Michael Gelb reminds us, “True humility emerges from a sense of wonder and awe. It’s an appreciation that our time on earth is limited but that there’s something timeless at the core of every being.”

As Fyodor Dostoevsky, one of the insightful Russian writers I studied in school, once said, “The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for.” Line cooking led me to exactly what Dostoevsky describes.

One evening not all that long ago, I delivered some food to the table of a guest. He looked at me seriously and asked, “So, what gives you purpose?” I’m pretty sure he didn’t know who I was, and that he was just academically interested in how frontline people in food service sorts of jobs thought about “purpose.” I’ll admit I was sort of caught off guard, but I got myself grounded again very quickly and answered: “Everything!” I shared that there is purpose in delivering great experiences to guests and coworkers, in teaching the history of the food and the cultures from which it comes, in trying to contribute to our community, in showing that we can slowly work to rebalance inequities in our ecosystem, and in our drive to learn and continue to improve in all we do.

Around the same time that I was starting to cook in restaurants, Carl Rogers wrote a book entitled A Way of Being. In it, he shared how his work had altered his worldview, helping him over the years to develop “a point of view, a philosophy, an approach to life, a way of being, which fits any situation in which growth … is part of the goal.” This is exactly what happened to me with food and cooking.

How has it all played out? In the forty-six years since I started as a line cook, I’ve learned from many remarkable folks: Paul Saginaw, with whom I opened Zingerman’s, began as the general manager at Maude’s the same day I started washing dishes there. To this day, we still like working together! Frank Carollo, a line cook at the time, trained me. We became friends, and twenty years later he opened Zingerman’s Bakehouse with us. Louie Marr taught us the basics of cooking and running restaurant kitchens, and today he still helps oversee all our construction projects. Over the years, I got involved with organizations like the American Cheese Society, Oldways, the Specialty Food Association, and Southern Foodways Alliance. Cooking and studying, figuring out all along how we could get better, more traditional food to Zingerman’s, and then how to get people—most of whom knew little about artisan food back then— to want to buy it. Learning to continually taste, smell, and appreciate, and then sharing those experiences through teaching and writing, became a way of life.

The American food world has come an enormously long way since we opened the Deli in March of 1982. Looking back, I can see now that Paul and I were a small part of a big culinary revolution in this country. That revolution has radically (if all too often, inequitably) changed the way millions of people all over the country think about, cook, and consume their food. And while that revolution was unfolding, food and cooking were coming together to change my life in big, big ways.

I can now say with certainty: I hope that what happened to me happens to many others as well. What gets you going may not be cooking, but there are thousands of intriguing, difference-making professions into which one can pour one’s passions. As Paul Goodman, a good Jewish boy who actually did go on to be a professor (and also a philosopher, playwright, poet, and anarchist), put it, “Having a vocation is somewhat of a miracle, like falling in love and it works out.” Sure enough, Goodman’s poetic statement, for me, proved to be true.

Given all that, I feel fairly confident in saying, it’s all worked out.

Printed in Ann Arbor and illustrated by Zingerman’s own Ian Nagy, the chapbook includes Weinzweig’s “18 life lessons” and his tips for making “marvelous meals on the fly.” It’s available at Zingerman’s Deli, Roadhouse, and Coffee Company, and online at zingermanspress.com.