No one was expecting a global pandemic in November 2019, when voters passed a twenty-year, $1 billion bond for the Ann Arbor Public Schools. The plan was spectacular enough: update the district’s school buildings, which had an average age of sixty-seven years, for the twenty-first century.

But it proved invaluable in March 2020, when Covid-19 drove students and teachers out of schools and into virtual learning. When they finally returned a year later, it was thanks to newly available vaccines and tests—and safety improvements paid for with money from the bond.

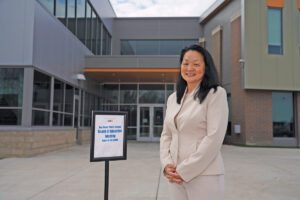

“Because we had the bond program in place, we were able to move quickly,” says then-board president Rebecca Lazarus, who left office at the end of December. Bond money allowed them to “make sure that before we sent our teachers [and] students back in, that the HVAC systems were upgraded.”

“We were able to have a recommissioning of every air system in all of our buildings,” confirms superintendent Jeanice Swift. “We were able to upgrade our filters and make sure that we had the very best in ventilation. We were able to do a similar process with our water filtration system” to ensure it remained safe during the months the buildings were closed.

The teachers union had stayed neutral on the bond—some members were still smarting from recessionary pay concessions and past clashes with Swift. But the upgraded air systems were “super important” to returning to in-person learning, says current union president Fred Klein. Having the money to do them “certainly was a good thing—and timely.”

Even in normal times, running a school district is a high-pressure job. “It’s a hot seat,” says Lazarus, “especially in this climate of politics and unrest.”

The average superintendent’s tenure in Michigan is less than four years. Swift’s predecessor, Pat Green, stayed less than two. And that was before pandemic stresses piled on to create what former trustee Andy Thomas calls “an almost unmanageable situation.” The atmosphere, then-board president Bryan Johnson told the Observer two years ago, got “very nasty and very threatening.”

Last year, Johnson and two other incumbents chose not to run for reelection, while remote-learning critics fielded a two-person slate. But the slate lost, and Swift survived. “It is totally unprecedented,” says Klein. “I’ve been in the district thirty-three years, and her tenure is the longest.”

—

Swift’s endurance is even more impressive because she wasn’t Ann Arbor’s first choice: When the board was searching for Green’s successor, it passed her over in favor of another candidate. She got the job only because the first choice took another offer elsewhere.

Green left less than halfway through a five-year contract. With state funding still depressed in the wake of the Great Recession, she’d cut 350 jobs, including 233 teachers, but still left the district facing a $10 million deficit—with a fund balance of just $5 million. When Swift arrived from Colorado Springs, where she’d been an assistant superintendent, one of her first tasks was to apply for a loan, in case it was needed to meet payroll.

It was never needed. Then-board president Deb Mexicotte told her that “cutting is not the strategy,” and “that has always been my model,” says the petite and poised administrator. “That’s probably what made us such a good match.”

Instead, Swift recalls, she advocated “adding value through opportunities, through connection, through programs, and through enrollment.”

She started with A2STEAM at Northside. The name is an acronym for science, technology, engineering, art, and math, and the new curriculum quickly turned an underutilized building into a nearly 600-student K–8 magnet school.

Next came the demanding International Baccalaureate program. It, too, was placed in schools that had been less popular, starting at Mitchell Elementary and Scarlett Middle School before going on to Huron High, and turned enrollment around.

A “schools of choice” program brought in hundreds of students from other districts. But “the largest increase in enrollment is from among our own students who live inside our Ann Arbor boundaries,” Swift says. Though the city itself is built out, parts of the district reach west almost to Dexter and south nearly to Saline. Developers are building homes there, and families are buying them.

—

Taken together, the changes brought in more than 1,500 new students in Swift’s first five years, an increase of 9 percent. Because Michigan ties funding to enrollment, that ended the financial crisis.

But one reason superintendents rarely last long is that even successful ones make enemies. And former trustee Andy Thomas says that Swift crossed the teachers’ union.

When Swift arrived, Thomas says “what we were hearing from parents was overall ‘we’re really happy with the Ann Arbor schools. But in my child’s school, there is this one teacher, who’s just not very good—not just ‘not very good’ but just plain bad. And everybody knows it [but] nothing ever seems to change.’ And we told her that if she would tackle that, then we would support her absolutely.

“I wasn’t overly impressed with Dr. Swift when I first came on the board,” admits former trustee Rebecca Lazarus. But once “you talk with her and you hear the facts that she’s basing her recommendations on to the board, you appreciate where she’s coming from … You can ask questions, and she has answers.”

“It’s a long process, and it involves a vote on the part of the board to terminate,” Thomas says. Before he stepped down in 2016, “I can think of twice that we did that. It might have been three.” Others were “encouraged to retire,” he says. They were told, “‘We can do this the easy way, or we can do it the hard way. If we do it the hard way, it’s not gonna be very pleasant for any of us, but we’re going to have to come to a parting of the ways.’

“I don’t think it was a huge number, [but] there were certainly a number of teachers who left during the first couple of years,” Thomas says. Swift “ran into a lot of opposition from the union, which is understandable, but that didn’t stop her … And I give her a lot of credit for having the courage to do what some previous school superintendents had not been willing to do.”

Swift’s educational initiative, though popular with students and parents, also caused some friction. The union agreed to the administration’s plan to open A2STEAM, but fought the International Baccalaureate, because teachers at those schools would have to reapply to teach the new curriculum or transfer to another school.

Swift and the board went ahead anyway—and did it again when the union refused to reopen its contract to renegotiate terms the district said were unsustainable. With that, then-union president Linda Carter told the Observer in 2015, “the ability to collaborate went down the toilet.”

Three hundred furious teachers, parents, and students packed a board meeting at Skyline High to condemn Swift and the board. And in the next two elections, union-backed candidates won four seats, ousting Mexicotte in the process.

With a majority of the seven-member board, the union-backed candidates could have tried to remove the superintendent—a prospect that, Thomas said at the time, left him feeling “north of morose and south of suicidal.” But instead, Swift won most of them over.

Lazarus was one. “I wasn’t overly impressed with Dr. Swift when I first came on the board,” she admits. “I had questions about some of the decisions that she was making and the district was making.

“But once you understand and you talk with her and you hear the facts that she’s basing her recommendations on to the board, you appreciate where she’s coming from. And you appreciate that she has done her homework on things, and you can ask questions, and she has answers.”

Swift says it came down to “building relationships over time and going through hard things [together]. We’re stronger as a result of the hard times we’ve been through.”

—

No time was harder than the pandemic. When Governor Whitmer ordered a statewide shutdown in March 2020 and AAPS closed its buildings, administrators, teachers, and families dove into online education overnight. A “continuity of learning plan” designated three online platforms and delivered thousands of iPads and Chromebooks to students, plus mobile hotspots for households without high-speed internet. With the help of nonprofits like Peace Neighborhood Center and Community Action Network, hundreds of thousands of meals were distributed to low-income students who normally would be eating at school.

But younger students especially had trouble sustaining attention online, and students and staff wrestled with tech issues. With workplaces closed, parents pulled double duty, working from home while trying to keep an eye on their online learners. And almost everyone felt the loss of face-to-face contact.

When the schools didn’t reopen that fall, a group called Ann Arbor Reasonable Return began to press the board to reconsider. The board held fast until January, but after the first vaccine was approved and Whitmer called on schools to reopen, members voted to begin the process—only to reverse themselves in February, directing Swift to return only special ed students to the buildings that school year.

One week later, the board reversed itself again, accepting Swift’s recommendation to offer in-school classes to anyone who wanted them. Citing improved access to vaccines and rapid tests that reduced the risk, she’d lobbied members individually beforehand, and all but one agreed.

Elementary students went back on alternating-day schedules in March, followed by middle and high school students in April. Single schools would still close temporarily during outbreaks, but by fall things were almost back to normal.

Surprisingly, state standardized tests during the remote year seemed to show improvement. Swift says she put those results “in parentheses,” however, “because many students chose not to test, and those who did test tested in a very different format.” That caution was validated when in-person testing resumed: Instead of rising, average scores had instead fallen significantly.

Swift says remote learning hurt some kids more than others. “Across the country there were significantly greater impacts among our more vulnerable students and families. Here that includes second-language students, students with special learning needs, students in poverty, and students of color.”

The schools compensated by very specialized intensive programming for those students over three summers, paid for with federal money. Swift says they’re seeing an “upward trajectory,” and are working with school staffs and parents to “personalize that program by child.”

“We are very dedicated to learning recovery at this point,” says board president Jacinda Townsend Gides. Students were testing again in April, with results expected about six weeks later.

—

The other pandemic aftereffect is stubbornly stagnant enrollment. After years of growth, the headcount fell 5 percent, to under 17,000 students, and has yet to recover significantly. Because Michigan students carry their funding with them, that’s a threat to the district’s bottom line.

The impact initially was mitigated by Covid relief programs—Swift says the district got about $24 million from the federal and state governments over the last three years—but now that’s done. The district had to dip into its fund balance last year, and Swift expects they’ll have to do so again this year.

Though it’s nothing like the situation she inherited—the reserves are budgeted to end the fiscal year in June a bit under $18 million—Swift says it will be the last deficit. They plan to analyze everything added during the pandemic, from physical property to day-to-day operations, to see what can be reduced or eliminated.

Swift points out that the district continues to gain residents, and the past and present school board presidents believe enrollment will increase. “Parents are still having a little PTSD from the Covid shutdown,” says Lazarus. But she thinks “parents will start bringing their kids back slowly once they feel confident that the school district will be consistently open.”

“As a parent who’s around parents, I think that it will bounce back,” concurs Townsend Gides. “The quality of education that AAPS delivers remains very attractive to parents, and now that we are back in full swing, I anticipate them coming back.”

If they don’t, though, teachers will have cause to worry, because their salaries are the schools’ biggest expense. If it comes to that, union president Klein says, “Our advocacy is for right-sizing the district through attrition—people retiring, people resigning.”

But for now, at least, they’re getting a little relief: In March, the union and administration reached a new contract with a 2 percent raise—the teachers’ first since 2018—and a 1.7 percent increase in the district’s contribution to their health care.

“We have a very collaborative relationship now,” Klein says. “I’m optimistic that we will be able to make more gains for our members in that next round of bargaining.”

—

Swift’s own career may yet take another turn: She’s been a finalist in three job searches in the last five years. She says she was recruited every time, because “there are calls that come in that you just have to think about.”

“I’m not surprised at all that her name is circulated when school districts are looking for a new superintendent,” says Townsend Gides. “Dr. Swift has been an incredible superintendent.” The board’s goal, she says, is “to create a situation where Dr. Swift wants to stay.”

While any superintendent’s job is challenging, the board president says, it’s particularly so in Ann Arbor “There are so many competing constituencies,” she says. “There are a lot of concerned parents.”

Swift agrees, but says the district’s engaged parents are also its strength. “What is important to me is for all of us to continue to come to the table together. We’re only going to be able to get through our challenges that we face by bringing ourselves together.

“There’s never been a time where public schools are more critical, more important to our future as a country, than now,” Swift continues passionately. “We just need to remember, on days when the challenges seem steep, that we do have the fundamental components in this community: a highly engaged and caring community and a top quality in our public schools’ teacher and staff team. There is no better anywhere.

“It’s been a rollercoaster for these three years,” she says, but “I think that will level out, and then we can begin to focus on building [our] strength and preparing for whatever’s around the next corner.”