After doing poorly in school,

I learned that I could work. I

was really good at it and I got

praise for it—from my parents,

my customers, and my crew.

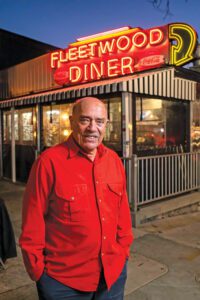

I wanted my own place. | Photo: Mark Bialek

I opened the Fleetwood Diner on January 6, 1972, at 11 p.m. The late start was to catch people coming out of the nearby bars, and one of the first customers through the door that night was a guy named Jay: White, around 240 pounds, and farm-boy tough. His hands looked like he could change tractor tires without a lug wrench and the word was that he’d been in Jackson Prison for stomping a state trooper’s eye out in a fight.

Now here he was, taking a seat at the counter in the place I’d just opened. Moments later, in came Chucky, a Black man, just as thick and tough as Jay. He sat down a few stools away.

Jay said, not exactly to me, “Gimme some milk—white!” And Chucky announced, “Gimme some milk—chocolate!”

Sounded incendiary to me. I could almost see nearly 500 pounds of raw human animosity going at it right there and destroying my new diner.

I was sweating bullets, but by some miracle, it didn’t come to blows. Still, I was sure that wasn’t the end of it. When I finally closed at three the next afternoon, what little sleep I got was fear-addled. I had to figure out how to save my dream—and avoid getting my butt kicked—the next time Jay and Chucky met up.

And then it came to me. Just a gamble, but I had hope.

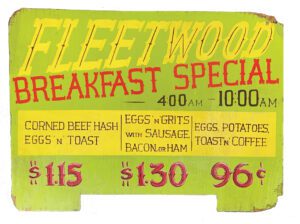

By the next time they both showed up, I had a new item on the menu board above the counter: Grits. “Eggs ’n’ Grits, with Sausage, Bacon, or Ham. $1.30.”

When they saw it, Jay turned to Chucky and said “Haven’t seen grits up here since I was back on the farm. You eat grits, right?” Chucky said, “Uh-huh” and that was it.

They’d found some common ground. They still didn’t like each other, but the Fleetwood Diner was over that hump.

—

I was born in 1944, so I would have been four when my parents moved to Ann Arbor. My father had been hired as a writer for the Ford Times, a monthly travel magazine for Ford customers. The GIs were back from WWII taking advantage of the GI Bill, and housing was extremely tight. People lined up at the Ann Arbor News building on Huron St. when the paper came out at 1 p.m. to look for rentals.

Our first home was an upstairs apartment on S. State near where the Produce Station is now. The next was at a farm north of town on Joy Rd., so I started kindergarten in the one-room Foster School on Maple Rd. It had an outhouse.

My mother told me that when she took me downtown on Saturday nights in the early 1950s I heard German spoken on the streets. I remember four shoe stores on Main St., two dime stores, Bertie Muehlig’s beloved dry goods store, and her grand home where the M Den is now. On Saturdays, my parents would drop me off at the paired Orpheum and Wuerth movie theaters, where a double feature and intermission stage show cost twenty-five cents. (Cheap babysitting.)

From Joy Rd. we moved to Pittsfield Village, where there were lots of kids at Pittsfield Elementary and the classes had twenty-five or more students. That was the beginning of my poor academic performance. By the time we moved to Burns Park, my parents were so elated when I managed a C on a social studies test at Tappan Jr. High that we went out for lobsters at the Allenel Hotel.

I got a paper route about then, starting at 4 a.m. to deliver the Detroit Free Press. But school never got any easier and I didn’t graduate with my class in 1962. After I failed again the next year, I just gave up and started working full-time.

There were a lot of jobs for untrained people in the 1960s and I had a new one every few months: Argus Camera, Reynolds Chemical in Whitmore Lake, Pittsfield Market sorting bottles, swinging a pickaxe and pouring foundations, pulling shifts at the Michigan Union pool room, and working at Ford’s experimental foundry off Telegraph Rd.

In 1967 I started at Red’s Rite Spot at William and Maynard as a late shift dishwasher and cleaner. I earned around $1.50 an hour. Red was a proud, self-described hillbilly and tough-love ex-drill sergeant from WWII. He was a prankster who’d sometimes cut off a customer’s tie, then flip him $10 to buy a new one. One of his favorite expressions was “You dumb shit.”

I earned it after doing an excellent job of extracurricular cleaning under the thirteen-stool counter but forgetting to mop the scouring power off the floor when I was done. But he was smiling when he said it, and once he saw that I was willing to work, he showed me how to cook eggs over easy by flipping a pack of Marlboros in my hand. I learned to handle the sociology of balancing students, silk-stocking shoppers from Jacobson’s, and professionals, to order, prep, and price diner food, and what it takes to be a good short-order cook (fast hands and a bad mouth).

And after doing poorly in school, I learned that I could work. I was really good at it and I got praise for it—from my parents, my customers, and my crew. I wanted my own place.

—

The idea for the Fleetwood came to me like a vision. I could see the menu, the type of customers, the quality and prices, even the colors I’d paint the awnings at the defunct Dagwood Diner at the corner of Liberty and Ashley. The current tenant was only using it to make vending-machine sandwiches. He’d covered the windows with contact paper, and there were signs strewn around from would-be operators over the last ten years who hadn’t followed through on their dreams.

The idea for the Fleetwood came to me like a vision. I could see the menu, the type of customers, the quality and prices, even the colors I’d paint the awnings at the defunct Dagwood Diner at the corner of Liberty and Ashley. The current tenant was only using it to make vending-machine sandwiches. He’d covered the windows with contact paper, and there were signs strewn around from would-be operators over the last ten years who hadn’t followed through on their dreams.

Downtown was on the rocks in 1972. Retail was still viable though getting tarnished as customers migrated to the shopping centers being built on the outskirts of town. The good factory jobs for the workers who lived on the Old West Side were disappearing. Argus Camera, King Seeley, Buhr Machine, and Cook Spring were gone or soon to be. The bars had pool tables and jukeboxes that played Merle Haggard, Hank Williams, and Patsy Cline.

There was broken glass and papers blowing in the streets. Family members weren’t taking over family businesses and the businesses weren’t worth much. The Union Bar, where the Old Town is now, had a shot-and-eggs special when they opened at 7 a.m.

The first lawyer I talked to about opening a diner there listened to what I wanted to do and told me “I’m gonna give you the best legal advice you ever got, and it’s for free: Don’t do it!” But a few days later I laid it out for another attorney, Bill Conlin, and he said, “Great idea!” and laughed and told stories about his own disastrous experience owning a French restaurant on Main St. He did all the legal work I needed to start the business and never charged me.

Ford had matched my retirement contributions, then gave me the money when I left. Between that and an extraordinary run of good luck playing low-stakes poker with my buddies, I was able to pay the sandwich guy the $2,000 he wanted for the Dagwood’s equipment and the nonexistent business. Don Reid, who had built the diner and run it successfully in the 1950s, let me have a sweet lease for $125 a month, rock-bottom rent even for the time.

I did the build-out myself. I’m not at all handy, but after a couple of weeks struggling, I realized that somebody had had the same problem before me and figured it out. Fortunately Schlenker Hardware was fifty steps down the hill on Liberty. I would just take my problems or broken pieces down there, and they’d send me in the right direction. If they didn’t have a widget I needed, they had the tools to make it. So I got it done.

—

I think I owed the deal to buy Hertler’s to Emma—she liked me because she’d seen me through the window at the Fleetwood cooking at seven a.m. Once during our discussions, she leaned over to her nephew and whispered loudly, “Sell it to him, Georgie. He’s a good boy—he gets up early.” | Photo: Peter Yates

The Fleetwood opened on the leading edge of a generational change downtown. On the opposite corner, workingmen and serious drinkers were still renting single rooms upstairs from the Union Bar. I’d see one amble down the block every morning with his newspaper, arriving on the top step at precisely seven when it opened for his morning shot-and-eggs. According to Wavy Drake, an out gay union steward who lived there, when residents passed away, none of the bodies had cash in their pockets or rings on their fingers by the time the police showed up.

But at street level, things were changing. Michigan was lowering the drinking age to eighteen, and Ned Duke and Buddy Jack had just remade Andy’s Bar into Mr. Flood’s Party, with shells of beer for twenty-five cents and live music on weekends to bring students down from campus. On the corner, Jerry Pawlicki would soon turn the Union Bar into the Old Town Tavern. Down on First St., Tommy Isaia and Jerry Del Giudice were starting the Blind Pig.

My “market study” for the Fleetwood was observing the scene from the ledge across the street. Wavy was about to be out of a job, and the tough guys with ducktailed hair, white socks, and pegged pants weren’t hanging around so much. I could see more cars and pedestrians than I remembered heading to and from the university.

I thought those new people might be willing to pay ninety-six cents for a better version of the eggs, potatoes, toast, and coffee that Wilson Loy was charging sixty-five cents for at his little diner by City Hall. Adding four cents’ tax made an even buck for a substantial breakfast. An even buck appealed to me.

My first menu was heavily influenced by the menu at Red’s: four breakfasts, including French toast and oatmeal in the winter, and six sandwiches, with five different soups a week and chili. I got bread delivered by Jack from Modern Bakery in Detroit, the best available at that time. I bought hamburger from Bobby Galardi’s father at Chicago Beef and I boiled their brisket to make real corned beef hash. The eggs came from Bilbee’s Farm.

Now almost all hash browns are purchased peeled, boiled, and shredded from distributors, and frankly they are mushy when cooked on a griddle and impossible to get crisp. I bought fifty-pound bags of potatoes and hired a guy named David who worked three hours a day, shredding them on an old fashioned box grater complete with the skins (that’s where the flavor is).

Our first night open we took in $150, thanks to the bar crowd. But the daytime business took a while to build. It started with the crew from the Sears tire and battery shop across the street, where the Beer Grotto is now. But the big turning point was due to one of the guys that I played cards with: he worked for the city, and started bringing workers from the maintenance yard down on Washington.

—

After a year of working sixteen hours a day, six days a week (we closed on Sunday), I sold half of the business to Rich Alford, who I’d worked with at Red’s Rite Spot. We then started to stay open twenty-four hours a day with each working twelve-hour shifts. I worked six at night to six in the morning. That was a lot easier.

I sold Rich the first half of the Fleetwood for $10,000. Two years later I sold him the second half for $25,000. That became my down payment on Hertler Brothers, the farm store half a block north on Ashley.

Three of the Hertler siblings had left their 1,000-acre family farm in Milan to come to Ann Arbor and start a livery stable in 1906. Two years later, Henry Ford introduced the Model T.

The Hertlers had grit and kept it going as a farm supply store, but that business, too, had pretty much disappeared as nearby farms turned into subdivisions. It had been on the market for eighteen months without an offer when I heard about it in the fall of 1974.

At the time, Gotleib Hertler was 102, Herman was ninety-four, and their baby sister Emma was eighty-nine. The price was $140,000. I gave the Hertlers my $25,000 down payment, and they gave me a land contract for the rest.

I think I owed the deal to Emma—she liked me because she’d seen me through the window of the Fleetwood cooking at seven a.m. when she came to work by cab. Once during our discussions, she leaned over to her nephew and whispered loudly, “Sell it to him, Georgie. He’s a good boy—he gets up early.” Definitely old school.

When I took over in 1975, there were three sizes of leghold animal traps and barbed wire in stock, some horse gear in the rafters, and dynamite and DDT on a shelf in the basement. I got rid of those, but I kept Emma’s heavy metal Steelcase desk, made in Grand Rapids. When I pulled out the top drawer, there in the stamp tray I found five little Hertler gold crowns.

I embraced the back-to-earth and organic gardening interest of the 1970s. We continued to sell bulk garden seeds out of a jar and to carry good garden tools, and I expanded on the pickling crocks and canning supplies the Hertlers had carried with some of the restaurant equipment that I had become familiar with at the Fleetwood. To brighten the store up I took the pictures of tulips and crocus off the windows where they had turned blue from the sun, and replaced the Hertlers’ thrifty 60-watt light bulbs with 100-watt bulbs.

Business took off, and after two years, I was able to purchase the parking lot next door. Our drive-thru barn was getting congested as we got busier and that gave us not only extra parking but also a new exit door to get customers out after they were done shopping.

The parking lot also gave us room to sell Christmas trees—Mark’s Supreme Happiness Trees and Greens—and display large quantities of imported pottery, plus have events like Sunday clog dancing and evening theater performances. Inside we had jam tasting contests with significant prizes, and gospel and boogie music for Midnight Madness. I think our most popular event was our Christmas party with a terrific Santa who gave out oranges to the kids and took their wish lists.

—

In 1979, I sold Hertler’s to Raupp Campfitters. Their biggest business was cross-country skiing, and they were looking to add complementary lines for the off-season. That didn’t work out as they’d hoped, and in 1985, Raupp sold the business and the rest of the lease to John McGovern, who’d worked for them since they bought it.

Meanwhile, my wife Margaret Parker and I had moved to the East Coast. Our daughter Jeanne was born in New York City, and we bought a small hotel in Castine, Maine.

It was a good business, but grueling, and back in Ann Arbor, Hertler’s was languishing. By the time the lease was up, it was down to about $400,000 a year in sales, from $1 million when we left.

My father had died, and my mother’s health was failing. So in 1997, we came back to Ann Arbor and the business.

John still owned the Hertler name, so we renamed the store Downtown Home & Garden and went back to work. I wanted to put a fence around the parking lot, and Margaret said, “Let me think about that.” And she came up with the idea of having, above that fence, an elevated hedge of hornbeam trees. In the summer, they shade Bill’s Beer Garden.

The Fleetwood has belonged to Andy Demiri since 1991—he’s the one who gets credit for the great neon sign.

Kelly Vore has owned Downtown Home & Garden since 2014. She still uses Emma Hertler’s desk—the one where I found the Hertler siblings’ gold crowns.

I held onto those crowns for years … until I needed a bridge. The dentist assured me that the real cost of a gold bridge came in making it, not the gold. I told him to go ahead and use the teeth.

So there it is in my mouth: a bridge made from five little Hertler gold crowns. Ask me sometime and I’ll show you.

Miss seeing you, Mark, at Downtown Home and Garden. You’re always friendly and happy whenever we run into each other. I think the last time was at your class reunion the previous summer. My sister was in the same class. I’ve enjoyed reading your “life story”, you write well. I’ll show this to my brother, Dan.

Mark, Thank you so much for the wonderful article on old AnnArbor. Although I left Ann Arbor inc the mid-sixties to move to Gainesville, FL, where Gary Loy, Richard Bassil, and Ken Elder lived. My father owned the building that became The Blind Pig (Moe Laundry and AnnArbor Diaper Service)’. Your article brought back many fine memories of having meals. At Dagwood Diner and Red’s Rite Spot. Red cut my Dad’s tie in to once. Anyway, thanks for the article and the memories.

Laurie Kroll