In March, Michigan’s Agricultural Preservation Fund Board awarded $2 million to eight farmland preservation programs across the state to purchase development rights that protect land for agricultural use. Five of the eight are in Washtenaw County.

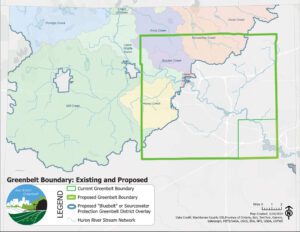

Filling in a corner in the Greenbelt area (in green, lower right) will enable the program to protect farms in Ypsi Township. The new “Bluebelt” will open up opportunities to protect wetlands and other natural features in Lodi, Sylvan, Webster, Freedom, Lima, and Linden townships. | Photo courtesy City of Ann Arbor

“The fact that Washtenaw County received the majority of the funds is not surprising or out of the ordinary,” emails Ginny Leikam, the county’s superintendent of parks planning and natural areas. “The same has traditionally been true with [United States Department of Agriculture] funds. The bottom line is we have more funded programs than most other places in the state—or most of the country possibly. Funded programs means we have projects ready to go and matching funds available.”

Ann Arbor continues to explore new opportunities to safeguard its natural resources. In March, city council approved a measure to protect Ann Arbor’s drinking water by expanding the Greenbelt to incorporate all Washtenaw County townships within the Huron River watershed that are upstream of Ann Arbor. Working with the country’s Natural Areas Technical Advisory Committee, it will look for opportunities to protect wetlands and other natural features in the new “Bluebelt” in Lodi, Sylvan, Webster, Freedom, Lima, and Linden townships.

At Ypsilanti Township’s request, council also approved a second expansion of the original Greenbelt boundaries to include the township’s northeastern corner. Ypsi Township is home to many beginning farmers who need land, but has yet to participate in publicly funded conservation easement programs.

The Greenbelt has protected 7,600 acres of farmland since its thirty-year millage passed in 2004. That represents 18 percent of available farmland in its coverage area, and Remy Long, the city’s deputy manager for natural area preservation and land acquisition, believes the total could reach 25 percent by the end of the millage. With county-level conservation efforts, township programs in Scio, Webster, Ann Arbor, Dexter, Augusta, Northfield, Salem, and Bridgewater, and private conservation groups, Washtenaw County is well placed to maintain its diverse natural areas and its agricultural heritage.

Preserving farmland doesn’t guarantee that the next generation of farmers will be able to access it, however. A 2022 MSU Extension survey found that the biggest barrier beginning farmers face is land access, and they prefer plots between ten and twenty-five acres that are close to urban markets. Most protected parcels are much larger, and easement language often prevents them from being subdivided. That’s why the Greenbelt split a fifty- four-acre parcel it purchased through its “Buy Protect Sell” program into two.

Matt Demmon, owner of Feral Flora, bought one of the lots. He notes the importance of including multiple building envelopes in easement parcels that allow them to be subdivided. “Small vegetable/animal farmers need to live on their land,” he emails, and “often don’t need 40+ acres or can’t manage that much without a lot of staff who also need a place to live.”

Kristen Muehlhauser, owner of Raindance Organic Farm on North Territorial Rd., bought the other lot. “Though we purchased an old farmstead in 2018 to start our farm, we came to understand that our land was poorly suited for annual vegetable and flower production due to flooding,” Muehlhauser emails. “Purchasing this parcel of well-draining farmland at its agricultural value gives our farm a permanent home. The Buy Protect Sell program is an important bridge for first generation farmers to be able to run successful small businesses for the long term.”

“Land conservation will always be the primary goal of the Greenbelt, but we can target specific outcomes related to farm viability,” explains Long. “But at some point we hit a wall of innovation, or a threshold of what we can actually accomplish because it’s not the millage’s purpose.”

While the Greenbelt’s work is critical, it’s only one of a myriad of resources and efforts needed to preserve rural landscapes. Long says that his biggest regret in a career in conservation is that when the work is going well, no one notices. “People react to change,” he laments. “We’re doing cool, innovative, wonderful things. How many people know that?”

The Greenbelt isn’t the only organization that wants to get the word out about its impact. The Washtenaw County Conservation District is hosting panel discussions across the county where local conservation groups explain what they do. “People want the rural character—that was something we always hear from townships,” says Rosie Pahl Donaldson, the city’s natural area acquisitions supervisor. But easement programs are sometimes misunderstood, causing hesitancy around their use, especially in more politically conservative townships. The outreach is encouraging some townships that have previously eschewed easement programs to come on board.

“The real success story is all the programs here, the density, the geographic scope, the investment, that timeline,” says Long. “We’re not just all coming online right now—we have twenty-three years of work under our belts from all these programs over the years.”