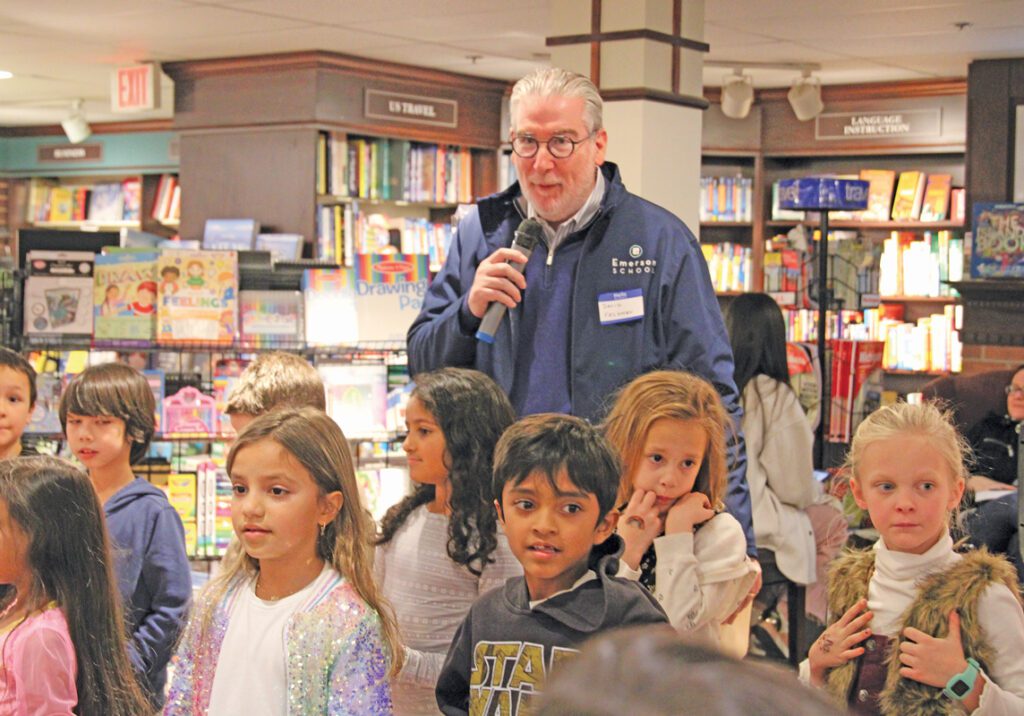

Head of school David Feldman (at a book fair at Schuler Books) says Emerson’s philosophy is “very simple: It’s being child-centered and thinking about learning by experience.” | Photo courtesy of Emerson School

Last summer, Feldman became the seventh head of Emerson School. It has about 340 students, from “young fives” through eighth grade, at its campus in Scio Township, and tuition this year runs from just under $18,000 to almost $27,000.

Jean Navarre founded Emerson in Plymouth in 1973. She had taught in suburban Cleveland, then moved to Michigan in the late 1960s to get a master’s in theater at the U-M.

She married here, then got a job teaching in Dearborn Heights. But according to her son William, she hated it. He emails that she felt “very constrained by an inflexible curriculum dictated by the state and the local school board,” so she left teaching. But in 1971, “on a whim,” she attended a lecture about “gifted children and their struggles in traditional school systems.”

His mother “loved gifted children,” William writes, and felt “they were being harmed by the rigid curriculum of public education.” With a “modest inheritance” from an aunt, she decided to create a school for them.

Named for Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose essays inspired her father, it opened with just eleven students. Convinced that her school “would only thrive in Ann Arbor,” William writes, Navarre moved it the next year to the West Side United Methodist Church.

By 1975, her marriage had dissolved and she was raising her son alone—while also caring for her father, by then incapacitated by Parkinson’s disease. Yet by the end of the decade, William writes, she’d seen it grow to more than 100 students, while also “dealing with its various crises both small and existential, and ultimately building Emerson a permanent home at Scio Church and Zeeb Roads.”

In Navarre’s day, Emerson required its “gifted” students to submit IQ scores. It no longer does, and now says it’s for “bright, engaged students.” Feldman says that twentieth-century educator John Dewey would have described Emerson’s educational philosophy as “progressive pragmatism … For me, I boil it down to something very simple: It’s being child-centered and thinking about learning by experience.”

Grades 6–8 were added in 1991. Combining elementary and middle schools, Feldman says, is “one of the few intentional designs left in education that has real meaning.” Middle schoolers need “to learn how to be good leaders, to have obligations and responsibilities, to be role models,” he says. “You want them to learn by being part of something bigger as opposed to having to grow up too fast to get to high school.”

“Some kids in middle school really struggle with their peer relationships,” agrees Tim Wilson, who was head of school at the time. “If they have the opportunity to work with younger kids, sometimes it anchors them.”

During his tenure, Wilson recalls, the recurring issues were diversity and affordability. “We’re going to create a global experience for these kids as best we can. But how? And how do we make these costs go away for some people, because there are so many people who should be at this school and can’t afford it.”

Marketing and communications director Jason Beckerleg emails that Emerson now provides roughly $1 million a year in need-based financial aid, and about 20 percent of students receive some assistance. The school considers diversity as a value in admissions, and 41 percent of students identify as people of color. After graduation, 85 to 90 percent of graduates go on to public high schools.

Emerson celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in April at Michigan Stadium. “We raised a significant amount of money,” Beckerleg emails, “with the bulk of it going to support our financial aid program—including a new middle-school scholarship in honor of Jean Navarre.

She had died in 2021 at age eighty, so William, now a professor of molecular genetics at the University of Toronto, attended on her behalf. “For me it was very surreal,” he says. “It was amazing to see this huge community of support and supporters. I don’t think my mom could have predicted or expected that Emerson would have grown to have the impact that it’s had on so many people.”

Does he have any advice for the school’s next half-century? “Just kind of keep the magic alive,” he says. “I think they’ve got a formula that works for human beings to grow: keep teachers and students happy and energized.”