When Alisha Carter graduated from Western Michigan, she was “looking for the mountains, looking for the water, and looking for a big city.” She met and married Max Carter in Seattle, but when they decided to start a family, her thoughts returned to her hometown. | Peter Matthews

Alisha Carter was raised in Ann Arbor, but after getting her teaching degree at Western Michigan University, she says, “I was looking for the mountains, looking for the water, and looking for a big city.”

She got her first teaching job in Seattle in 2018. She fell in love with the city and met her husband, Max Carter, there, marrying in 2023. But once they decided to start a family, her thoughts returned to her hometown. She and her husband, both thirty-one, and their six-month-old son now live in a house that they purchased in northwest Ann Arbor in April 2024.

“I always missed Ann Arbor—the slower pace of life, seeing familiar faces around town, being close to my family and friends of fifteen-plus years,” Carter says. She enjoys “going back to all of the wonderful restaurants, shops, museums, libraries, parks, and events that I loved growing up and now getting to share that with my family.”

Carter isn’t alone. While no one tracks how many Ann Arbor natives are returning to raise families, it’s common enough nationally that there is a term for it: boomerang migration.

Statistically, they’re lost in the city’s constant ebb and flow of young people. According to 2019–2023 American Community Survey estimates, Ann Arbor is actually losing more young and middle-aged adults than it is attracting. Yet a post-Covid environment with more remote work is enabling some young adults to return home. Phil Santer, Ann Arbor SPARK’s chief of staff, says the economic development group’s “tech homecoming” attracted roughly 300 people last year. “We absolutely are chatting with people that either want to move back in the area or are making that move,” he says.

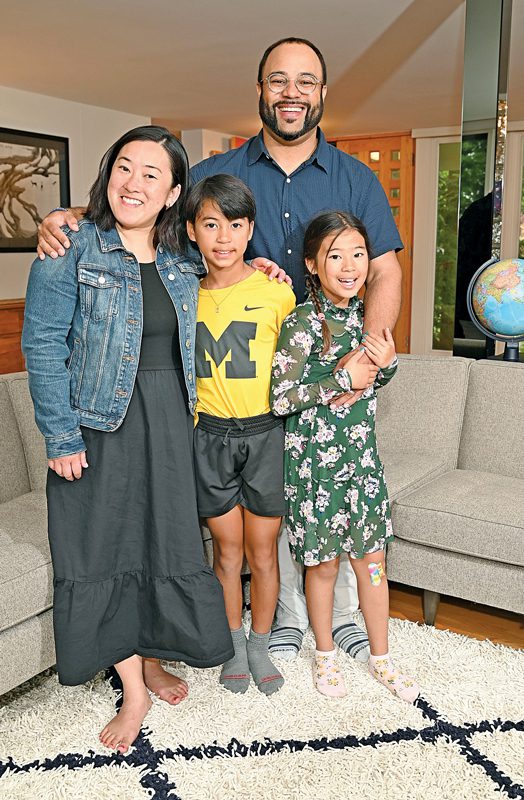

Oscar Barbarin and Katherine Wu are both from the area. They met when they were U-M students, and after spending time in India and Dallas, Barbarin moved to Chicago, where Wu was living. They eventually settled in Seattle before moving back in 2021, when their children were five and six.

They’re both forty-two, and both work remotely: Barbarin as a managing director at a California digital marketing firm and Wu as a supply-chain executive at Starbucks. “That was a huge factor in being able to make the move,” he says. “We never once had to consider leaving our jobs.”

Being closer to family is a major lure. Barbarin’s mother lives in Ann Arbor, and his father lives here for part of the year. Wu’s parents live in Canton, and they see them weekly. “In Seattle, we were so isolated. It was just the four of us,” he says.

When Alisha Carter found out she was pregnant, “I wanted to share raising my kid with my mom, like she did with her mom with me,” she says. She now works for Early On, a home-visiting program that provides services to children up to three years old with developmental delays or disabilities, while her husband is an insurance agent. She sees her mother once or twice a week.

Sarah Devereaux, who grew up in the area and moved back from Boulder, was raised by a single working mother. Her grandfather picked her up from school every day, and her grandmother helped raise her. She wanted that for her own children—as did her husband, Paul Devereaux, who grew up in Flint as a latchkey kid and is now a stay-at-home dad.

The couple, both age forty-two, moved to Ann Arbor in 2022 with their children, then ages five and nine. Initially they lived with Sarah’s mother in a house in Superior Township that she had found for them. When the house next door went up for sale two years later, her mother moved there. “I go on walks with her every morning,” Sarah says. “I love that she is one of my best friends.”

Sarah’s business partner, Nikki Patterson, is another returnee. Together they founded a leadership development collective that provides coaching, wellness retreats, and other support services for high-powered female leaders. Patterson, thirty-nine, grew up in Ypsilanti with lots of family around. She longed to raise a family here, but the lack of job opportunities initially held her back—until Covid hit and remote work opened up. She and her husband, David Patterson, returned in 2020 with their son, now five years old. They also have a three-year-old daughter and live in the Ann Arbor Hills area. David, who grew up in Tennessee, works remotely for a San Francisco–based public relations and communications firm.

Big-city problems also are factors. Barbarin said that during their last four months in Seattle, “anytime we would go to a public park, me and my wife would have to walk the park first just to see if somebody had been shooting up in a corner, because they would leave their needles just right on the playground.” Since the public schools were underfunded, they chose to send their child to private school—with the price tag for kindergarten at more than $33,000 a year, not counting required fundraisers and additional donations. Their children now attend Burns Park Elementary.

As someone of Puerto Rican and Creole heritage, Barbarin says, he “often felt isolated, excluded, or seen as an outsider” in Seattle. He says that in comparison, Ann Arbor is “more welcoming and less segregated.”

Carter said diversity was a draw for her too. She’s Black, and says that at her previous job in Seattle, she was one of just five Black employees out of more than 100. “I have a son who is biracial, and I knew I wanted him to grow up in a space that was diverse and accepting of others,” she says.

The impacts from climate change were also a factor in the move. When Patterson lived in Denver, the ash falling from wildfires was frightening. “You were carrying the baby monitor and the air monitor at the same time,” she says. “I thought, ‘We can’t live here anymore.’”

Lindsay Bellock Lieber, who lives on the northeast side of Ann Arbor, has fond memories of seating customers at Seva when she was a child. Her father, Steve Bellock, opened the restaurant in 1973 and sold it in 1997, and she often did her homework in his office above the restaurant. “On one of my very first school dances, I went on a double date to Seva and felt very cool,” she said. But after attending Brandeis University near Boston, she headed to Los Angeles, finding her passion as a casting director.

Lindsay and her husband, Adam Lieber, both forty-five, moved back to Ann Arbor in August 2020 with their two children, now twelve and seven years old. Many factors fueled the decision, including the cost of living, safety, a larger house and yard, and better public schools. “I was raised riding my bike around the neighborhood and walking home from school. We wanted a community where our kids were free and safe to do that,” she says. Though Adam grew up in L.A., he was game for the move.

Lindsay’s parents live less than a mile away, and they see them weekly. During Covid, her mother, a retired kindergarten teacher, helped teach her daughter to read. The two “have a great relationship,” Lieber says. “She can talk to my mom about anything.”

The move came with a big compromise: while her husband is able to work remotely for a small hedge-fund company, being a casting director isn’t conducive to such work. Though she occasionally gets jobs casting for commercials or industrial films, she doesn’t have a project every day and misses it. She instead keeps busy volunteering at her children’s schools and coaching and judging high school forensics.

That professional cost initially made her hesitant about the move. “But I also am not sitting in the car for two hours a day and paying a nanny while I’m sitting in traffic.” She says the trade-off was worth it. “Los Angeles was a great place to build my career and an exciting place to live in my twenties and thirties without kids. Once kids entered the picture, it was clear that raising them in Ann Arbor would be the right move for us.”

Oscar Barbarin and Katherine Wu also returned from Seattle. He says that they find Ann Arbor “more welcoming and less segregated.” | Peter Matthews

Drew Denzin, age fifty-one, boomeranged back into his childhood home in Burns Park: in 2004, he and his wife, Jen Denzin, welcomed a daughter and moved back to the house on Shadford where he was raised. After serving in the Peace Corps in Kenya, they had been living in Saline when his parents decided it was time to move to a one-story house.

“It was a little surreal,” Drew says, but also “super comforting to have a feeling that you know the bones of the house.”

They put on an addition, but after eleven years, they wanted something closer to the park and farther from Stadium Blvd. When an old friend’s father moved to Glacier Hills, Drew offered to show his house on Granger to young colleagues looking to move to the neighborhood. When he and Jen looked at it, they realized it needed a new electrical system, windows, and foundation. But it was closer to the park and they were ready to downsize. They sold his parents’ house, bought it, and did the renovations.

Their daughter is now twenty-one, and Drew says she’s still in touch with her own Burns Park friends. They also have an eighteen-year-old son. “Ann Arbor is a special place,” he says.

Allie Fahlsing, age thirty-two, and her husband Charles, thirty-four, both grew up here and met as counselors at Camp Algonquin. They moved to Boulder in January 2018—a city Allie describes as “like Ann Arbor with mountains”—after Charles got a job with a summer camp management software company there.

But in time, the distance from their families took a toll; both of their parents live in the Ann Arbor area, and they wanted to start their own family nearby. The pandemic was the major catalyst to return, since Charles could continue his work remotely. Allie was able to find a job as a social worker with Ann Arbor Public Schools.

They returned in September 2021 and their son was born in November 2023. Allie is now a stay-at-home mom. “We both knew how great of a childhood we had in Ann Arbor,” she says. “We have loved having my parents around to see [our son’s] connection with the two of them grow. That part feels really special.”

But the transition has been challenging for those purchasing their first home here. Like many growing cities, housing prices in Ann Arbor have escalated.

Drew was able to finance the purchase of his parents’ home through a land contract and got a “family discount,” paying well below market value.

Charles Fahlsing said it helped that interest rates were at record lows and that they found a house before it went on the market. Even so, they paid $445,000 for a 1,900-square-foot house.

When Stephen Lichtenstein, a physician, moved from Baltimore with his wife in 2023, they searched for several months before purchasing their Lower Burns Park home, outbid several times by those offering cash well above their price range. “It felt like any time a single house popped up, everybody was kind of pouncing on that all at the same time, so it was super competitive,” he said. He said many of his friends are looking for homes in Ypsilanti and the outskirts of Ann Arbor because of the challenging housing market.

Even though Barbarin and his wife had proceeds from the sale of their Seattle house, they searched for nearly six months. They made eight sight-unseen offers via video tours—all of which were rejected. “It’s a huge problem,” Barbarin said. “You start getting priced out really quick because a lot more people from the east and west coasts are flooding the market with cash.” They temporarily moved in with his father and eventually bought a home in Ann Arbor Hills in September 2021.

Carter says she couldn’t have bought a house without her parents’ assistance. They purchased a 1,383-square-foot home for $500,000 the year before she moved back and rented it out, then sold it to Carter for the same price in 2024 on a land contract. “Even with their help, it’s a stretch on a budget,” Carter says.

But she has no regrets. “I love being back,” Carter says. “Ann Arbor will always be home.”