After studying seven centuries of pandemics, the U-M physician and medical historian knows the best and worst of how humans treat one another when threatened by mass infections. But he says even he was “gobsmacked by the COVID-19 crisis.”

As scary as it is to see Ann Arbor’s schools and concert halls shut down, even more drastic steps are being taken around the world. “I think it’s almost a billion people [in China who] are under lockdown,” Markel said in mid-March.

“It’s a giant pyramid. At the top of the pyramid, at the apex, is the isolated and the sick. The next wedge are the quarantined–people you suspect of being ill or suspect of having contact with the ill.

“And then there’s the bottom wedge–we actually came up with the term–they’re ‘protectively sequestered.

“We are enacting a similar arrangement here in America,” he adds. “We’re putting [people] away before they have contact” with the virus. That includes nursing homes confining residents to their rooms and people sequestering themselves in their apartments and getting food delivered.

Markel started studying quarantines when he was in graduate school at John Hopkins in the 1980s. “I had finished my pediatrics training there and was getting a PhD in the history of medicine, and in the evenings I was volunteering in an AIDS clinic.

“A lot of my gay male patients and intravenous-drug-using patients would ask me, ‘Do you think I’ll be quarantined because I have AIDS?’ And I said, ‘No, it’s a sexually transmitted disease and [quarantine is] just not appropriate.'”

But people kept asking, “so I started to think about it. These people have been stigmatized on so many levels, it’s not an unreasonable thing to ask.”

That’s when Markel “started getting interested in the historical roots of quarantine–all the way back to the Middle Ages … I got interested in looking at immigrants who imported, or who were accused of importing, infectious diseases. And what happened is an era when quarantine was actually used–or misused–and misapplied to people society just didn’t like.”

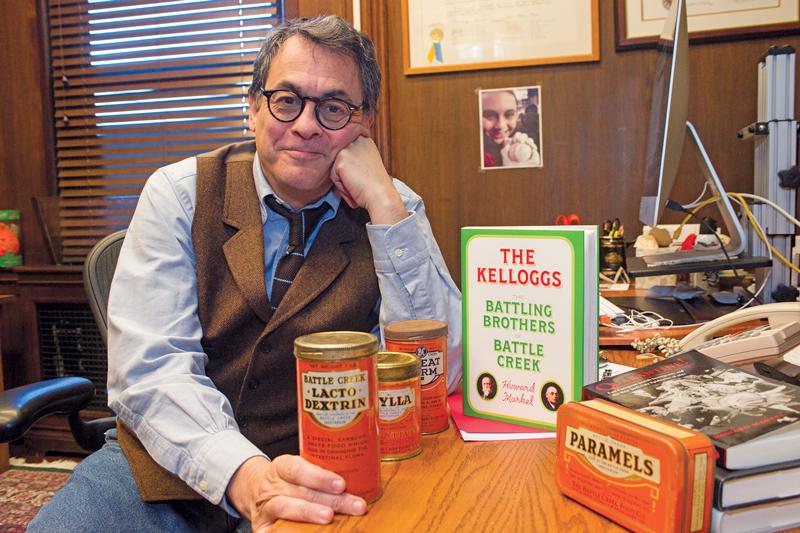

After writing two books–Quarantine! and When Germs Travel–Markel says, he “was perfectly content to put that topic aside.” But in 2005 he got a call from the Pentagon, which led to consulting “with the Defense Department and then with the CDC, from about 2005 all the way to 2016.” Along the way, he became a media mainstay as a national expert on epidemics.

Markel was teaching English 317–“Literature and Medicine”–in East Quad when “we all got an all-points bulletin from the [U-M] president that we’d be teaching long distance.” So in mid-March he was learning how to teach remotely.

It’s the prudent thing to do, but “it can’t replace the magic that happens with a professor in a classroom,” he says. And he’s been giving as many as seven interviews a day, providing perspective to media ranging from the Wall Street Journal and People magazine to CNN and the BBC.

Getting up at 5 a.m. and working late, “I have my hands full,” he says. But, he adds, “the very hard jobs are the health officers’ who are on the front lines, trying to manage this crisis.”

Why was Washington caught so flat-footed? “They get distracted by other things,” Markel says. “They get distracted by the spin of the moment. And we tend to have a government of political actors who are more interested in a game of gotcha–on both sides, mind you–than on governance.

“So it’s entirely predictable that we would be unprepared in a world that forgets about the last pandemic or epidemic and, almost as soon as it ends, goes along its merry way.”

In an interview on NPR’s On Point, he added that “history is littered with public health officials who either acted too early, and then everybody gets angry about that, because these are incredibly disruptive to human society and economics and so on. Or they acted too late, and then people get sick and or die. So … you really have to be the Babe Ruth of public health to knock that one out of the park.”

Markel tries to be Ruthian in his line of work. “I have a very narrow talent that I’ve learned to maximize,” he laughs. “I am a pediatrician, and I am a teacher, and I teach many different levels, from children to adults … I’ve gotten very good at changing channels and communicating in different points of view.”

What’s his message? “If you don’t have to be in a public space, don’t do it,” Markel says. “A lot of the choices of public gatherings have been made for us. Major League Baseball, my beloved baseball, did exactly the right thing. I would not go to a movie if I could see it at home.

“It’s circulating,” Markel says of the virus. “It’s not an issue of a contact anymore. It’s out there.”

He reminds people that other mass infections preceded Covid-19 and others will follow. “We’ve had six epidemics–two of them pandemics–in the last twenty years,” Markel says: “SARS, bird flu, H1N1, MIRS, Ebola, and Covid-19 … So it’s not like this problem is going away.”

He adds, “if you look at the last few lines of Camus’ The Plague, a book I teach every year, that’s exactly what it says–[Camus] was not an epidemiologist, but he got it perfectly.”

Humanity has “survived many, many challenges,” he says. “And I suspect, I hope, I believe, we’ll continue to do so, particularly if we remember we’re part of a community. And there’s no situation where we’re more part of a community than an epidemic. Because the microbes themselves are socially mediated, and how we deal with them is very much socially mediated.”

The next pandemic, he says, is “not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when.” So, along with preparedness and emergency drills, we need “experts thinking and talking about it and doing studies before it happens. And doing policy studies, too, because there’s a lot of policy implications–poor people are going to have a much harder time financially with quarantines than some, say, wealthier people.

“You have to talk about that before, not during. And frankly, after, people have this amnesia, and they forget all about it.”

So where does that leave us as we hunker down while COVID-19 crests?

“I think [the shutdown] may help to flatten the curve, so to speak, to lower the amount of cases … and hopefully will protect our most vulnerable Americans–the elderly and the ill,” he says.

“But we’re flying by the seat of our pants,” he adds. “Because anyone who tells you that they know the answer or can predict when this will be over is either lying or is foolish.”