Dr. Alvan Wood Chase of Ann Arbor was the genius behind a national best-seller–long before the New York Times best-seller list. He promoted his Dr. Chase’s Recipes; or, Information for Everybody to “merchants, grocers, saloon-keepers, physicians, druggists … harness makers, painters, jewelers, blacksmiths … barbers, bakers … farmers, and families generally.”

Chase’s kitchen recipes might not tempt today’s palates, since with no refrigeration, salt and vinegar were often used in food preservation. They can also be a little vague. One for yeast cakes, to be used in baking, calls for: “Good sized potatoes 1 doz; hops 1 large handful; yeast pt; corn meal sufficient quantity.”

His discussion of fruit-infused wines and brandies for the home sounds like a Temperance tract, writing under the heading “Spiritual Facts: That whis-key is the key by which many gain entrance to our prisons and almshouses … That punch is the cause of many unfriendly punches … That ale causes many ailings … That wine causes many to take a winding way home.” Yet elsewhere he testifies that the daughter of Wm. Reed of Pittsfield, when bitten on the arm by a rattlesnake, “was cured by drinking whiskey until drunkenness and stupor were produced….”–thus demonstrating that “The bite of the Devil’s tea is worse than a rattlesnake’s bite.”

Most of the explanations hyping Dr. Chase’s recipes focus on pseudoscientific accounts of the operation of various organs, which he purported to regulate through his homemade medical concoctions. Some may have briefly improved patients’ symptoms, only to expose them to far greater long-term risk. Touting his cures for “ague”–chills and fevers– Chase lists a dozen remedies but adds that “any preparation of opium as laudanum, morphine, &c……are valuable in ague medicine.”

—

Chase was born in New York in 1817. As a young man, he moved to Ohio and then Marine City, Michigan. Seeing advertisements in periodicals for individual recipes, he set upon the idea for publishing his own collection.

Looking to gain knowledge and advance his qualifications, he relocated his family to Ann Arbor to attend the U-M Medical School. Lacking the required knowledge of Latin, however, he had to content himself with monitoring some classes. The M.D. after his name was later acquired via a sixteen-week course in Cincinnati at the Eclectic Medical Institute.

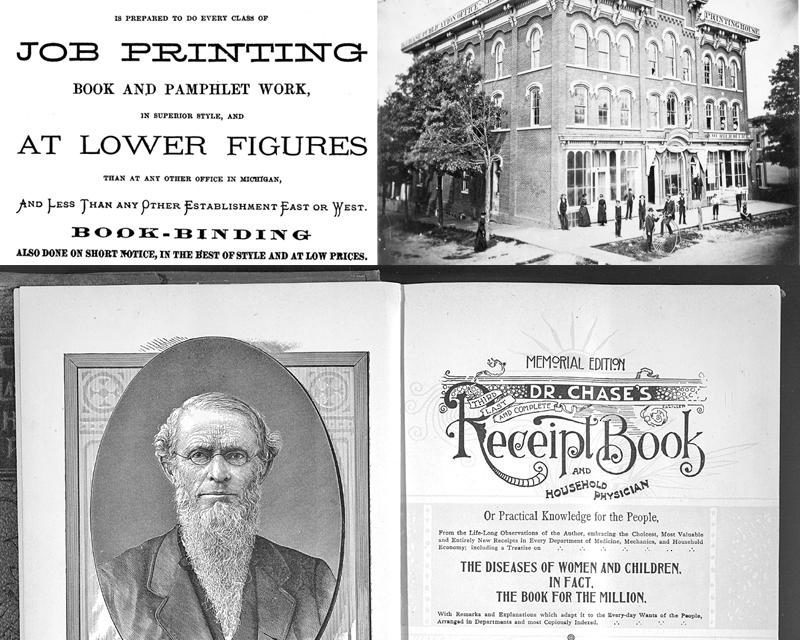

Chase collected recipes and advice from physicians, farmers, Native Americans, backwoods healers, and grandmothers, among others, and assembled them into books that advised readers on everything from treating injured horses to detecting (or indirectly abetting those making) counterfeit money. He launched his publishing business in 1864 on the northwest corner of Main and Miller and was so successful he soon had to greatly increase his space, celebrating the opening of his new “steam printing house” in 1868. He also published a newspaper, The Peninsular Courier and Family Visitant.

But soon Chase became obsessed by the fear that his medical printing empire would crumble. His endless immersion into diseases such as typhoid fever, pleurisy, cancers, and other infirmities also left him with a haunting sense of his own frailty.

Saddled with insecurities and convinced that he was near death, Chase sold his building and business to lumber baron Rice Beal in 1869. But his sense of impending doom proved premature: he would live another sixteen years.

—

With Beal’s medical publication business thriving, Chase jumped back into the game–despite a clause in the sale contract in which he’d agreed not to engage directly or indirectly “in the business [of] printing and publishing in the state of Michigan so long as Beal should remain in the business of printing and publishing in Ann Arbor.”

By 1872, Chase joined a number of local businessmen to form the Ann Arbor Publishing Company, with himself as president and business manager. First on the agenda was the preparation of Dr. Chase’s Receipt Book, which he promoted as superior to the Recipe Book he had sold to Beal.

When Beal sued, Chase claimed their contract should be voided as an “undue restraint of trade.” The Michigan Supreme Court disagreed: in 1873, it enjoined him against “being engaged directly or indirectly in the printing and publishing business in this state, or printing or publishing the second receipt book, in this state.”

By then, though, Chase had already set up business in Toledo, though he continued to live in Ann Arbor. He launched his new book in Ohio under the title Dr. Chase’s Family Physician, Farrier, Bee-keeper and Second Receipt Book: Being an Entirely New and Complete Treatise. It ran through seven editions between 1872 and 1878, followed by a revised edition in 1880. He also began manufacturing patent medicines, selling by mail order such concoctions as “Dr. A.W. Chase’s Kidney-Liver Pill”; “Dr. A.W. Chase’s Catarrh Cure”; and “Dr. A.W. Chase’s Syrup of Linseed and Turpentine, a certain cure for asthma, bronchitis, sore throat, croup, coughs, colds and consumption in its early stages.”

Despite the competition, both Beal and Chase were successful. After Beal died in 1883 and Chase in 1885, their businesses were carried on by their sons for years to come. In an odd happenstance, Chase’s final resting place at Forest Hill Cemetery is within view of the medical school that denied him a degree.

The last edition of his book was completed only two months before his death. Bound in oilcloth, the 865-page “memorial edition” included nearly 3,000 prescriptions and recipes. It was sold as far away as Australia.

In earlier generations, the material Chase collected and disseminated would have been passed down from generation to generation through oral tradition. While few would recommend following his medical advice today, his tomes are like lost treasures for those searching for old family recipes and archaic remedies.