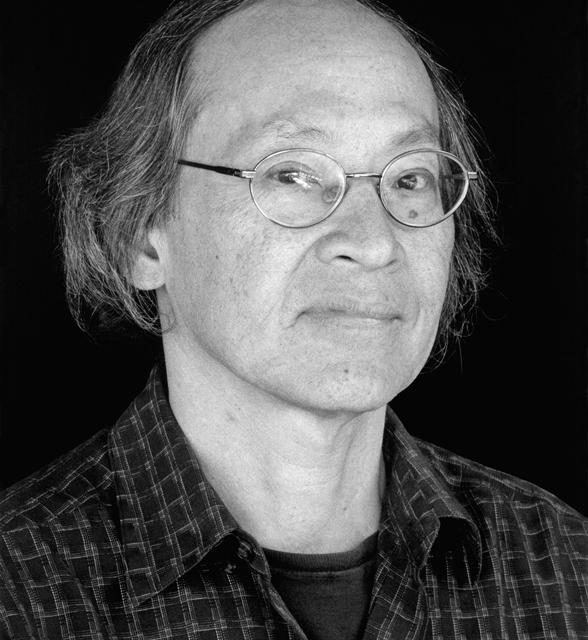

Between the time I write this and the time you read it, we will know whether or not Arthur Sze has won the National Book Award for his latest collection of poems, Sight Lines. That his book has appeared on this short list is another in a long list of recognitions that include a near-miss on a Pulitzer. He is a past chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. This makes Sze sound as if he’s one of the Grand Old Men of the poetry establishment. But once you know his poems, that impression seems entirely wrong.

Almost twenty years ago, Sze published The Silk Dragon, a very personal selection of translations from the Chinese. In eighty pages he skipped through 2,000 years of Chinese poetry, but his purpose was not to give a survey of Chinese verse. It was to find inspiration, a way back to his own practice, in the example of the careful and precise observations of poetic forebears. His poems, like the ancient Chinese poems he has so meticulously translated, are built on what seems an almost spiritual belief in the power of precise observation of the things we see around us.

In Sze’s own work, however, those things are shaped by an imagination that puts them in unexpected relationships with other objects in the world. In an early poem in Sight Lines, the wildfires that are devastating the western states are set next to a woman making delicate confectionaries or a water drop that “hangs at the tip of a fern.” At the end he allows himself to go from the smallest moment to an apocalypse in just a few lines:

In the West, wildfires scar each summer–

water beads on beer cans at a lunch counter–

you do want to see exploding propane tanks;

you try to root in the world, but events sizzle

along razor wire, along a snapping end of a power line.

The “sight lines” of the title are presented at several points throughout the book. They appear as simple fragments running down a page, at first seemingly unconnected. As we go back to the moments in these fragments, we realize that there is an imaginative jump between them. In the title poem, a collection of such fragments–including images of nuclear explosions, horses, and walks in the desert–ends:

I’m walking on silt, glimpsing horses in the field–

fielding the shapes of our bodies in white sand–

though parallel lines touch in the

infinite, the infinite is here–

Each line grows out of those that came before (for instance, “field” in one line becomes a verb in the next), until at the very end the poet brings the infinite into this very moment.

Arthur Sze reads his poems in the U-M Museum of Art on Tuesday, Dec. 3.