“It was the grandest thing I ever experienced. The most beautiful comradeship, love and perfect understanding was established in those four hours that you call awful,” said Jane Hicks, as she told of the events that cost three of her friends their lives.

“They are happy,” she added, “I know they are. In those last few hours when we faced death together, we talked it over. Life held a great deal that was dear for all of us, but death was also attractive. We said among ourselves, that we had never done anything in our lives that we could really regret.”

—

Ella Rysdorp, who had left the U-M in 1912 to teach at Spring Lake, was visiting Ann Arbor during spring break. She was staying with her friend Jane Hicks and spending time with John Bacon and Archie Crandall.

On Sunday, March 30, 1913, the four friends decided to go for a canoe ride. Barton Dam had been completed since Rysdorp had left Ann Arbor, so the four chose to spend the afternoon on the new reservoir. They paddled up the river to the dam, where the men carried the canoe up to the pond. After spending about four hours on the water, they set out for home.

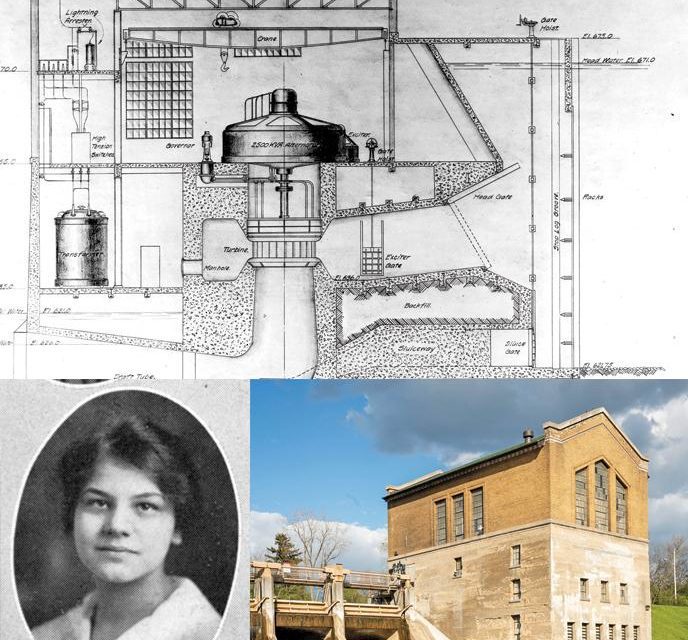

Back at the dam at about 6:30 p.m., as evening was falling, Bacon and Crandall carried the canoe down the stairs along the side of the powerhouse. They placed it in the tailrace, where water exited the turbines.

“When they paddled up the river in the afternoon, the machinery was stilled,” the Michigan Daily reported on April 1. “The tailrace with its smooth cemented side proved alluring and the canoe was guided up to the … landing without any thought. The water was still. Everything was safe. But the return trip was different. It was night and thousands of incandescent lights were clamoring for fuel. Hence the turbines were turning and tons of water poured down the tailrace transforming its calm surface into a whirlpool.”

Warning signs had been ordered but were not yet in place. The girls were at first reluctant to enter the craft, but the men laughed off their concerns. Bacon was the last to seat himself in the canoe. As soon as they pushed off, an eddy drew the canoe back toward the powerhouse. It hit the wall, crumpled, and threw the passengers into the water, where the current swept them under the arch of the building.

They found themselves on a concrete ledge about four feet wide. Standing in darkness with water up to their necks swirling around them, the friends could speak only by shouting.

Hicks recalled Bacon saying, “We came out under that arch. If I can dive into the deep current I can swim out and get help.” Then he set out into the darkness. A moment later he was thrown back onto the ledge. Three times Bacon tried to swim out under the arch, but each time he was tossed back.

“Part of the turbine discharge,” the Daily Times News explained on March 31, “striking the arch of the wall coiled upwards and back, a great wheel of water with the top running always toward the ledge.”

Bacon made his way along the ledge and found a small pipe vent with warm water running from a boiler. The four gathered under it to stay warm.

Bacon continued to explore and found a wooden trap door in the ceiling. He tried to push it open but was unable to do so.

Returning to the others, Bacon told them of what he had found, but they refused to believe him. Once again, Bacon tried to swim out but was tossed back onto the ledge. Then he slipped into the water and disappeared.

—

Standing under the pipe vent, Crandall, Rysdorp, and Hicks yelled for help.

Two stories above them, Walter Yost, the night operator, began his regular inspection. A floor below, as he passed the door to the transformer room, Yost heard a voice but could not understand it.

“Pretty late for anyone to be out on the river,” he thought, relayed in an account he later gave to the Daily Times-News. He completed his inspection and made his way upstairs.

According to the paper, Hicks then said, trying to laugh, “This is a poor way to entertain a guest.”

“It’s not your fault,” answered Rysdorp.

Suddenly Hicks called out, “Where are you?”

Rysdorp did not answer.

Hicks and Crandall were now alone. “We talked it over,” recalled Hicks later. “We said we had no fear, and we trusted in God.” Added the reporter, “Over both there was that calm that comes when one first sinks into refreshing sleep.” Hicks recounted, “We felt that when we were completely numb, we too would slip off the ledge to our death, but we were no more desperate than we had been at any time.”

“‘It’s to be just as God wants it, Jane,'” she recalled Crandall saying. “‘If someone comes for us, it is all right, and if not, we are ready to die. We have done our best all our lives, and if it’s time to die, we will not complain; we will be brave about it.'”

At about this time another worker entered the transformer room and heard noises.

“Don’t they ever go home?” he reportedly wondered, as he climbed up the steel spiral stairs to the dynamo room.

Yost made another inspection of the transformer room at about 10 p.m. and again heard voices. This time he went back upstairs and told the other two workers, “Something’s wrong on the river. I’ve heard somebody calling twice tonight.”

The men used lanterns to search the riverbanks but found nothing. Yost again went to the transformer room and listened. He heard someone calling faintly.

He moved a heavy toolbox on top of a trap door, the same one Bacon had found before. He then lowered an incandescent light at the end of a wire into the space between the floor and the waters below. All he could see were the seething water and the wrecked wood of the canoe.

“Help, help,” a voice cried from under the boiler room next door.

Yost pried up flooring, which was made to be removed when access to the discharge pit was needed. Again he lowered the light and saw two heads sticking out of the water.

Yost tied a rope into a loop and threw it to the couple. Crandall caught the rope and slipped the loop around Hicks. Crandall placed his arms around Hicks, so they could be pulled up together.

“Are you ready?” called Yost. He then pulled the rope up. It was hard at first, but then there was a splash, and the weight was lighter. Yost pulled on the rope, and Hicks came up through the floor, alone.

Yost looked again, but there was no trace of Crandall.

Hicks was taken to the Yost home, and a doctor was called to attend her. Yost called her “the gamest girl I ever saw in my life.”

According to the Times-News, when Hicks finished her account, she said, “I do not believe the others are dead. We were all good swimmers, and I believe they swam to some place of safety, and will still be found.”

In this, she was mistaken.

The bodies of John Bacon and Archie Crandall were recovered on April 15. Ella Rysdorp’s body was found on April 20.

Jane Hicks graduated from the U-M in 1915.

Electrical demand quickly exceeded what the Huron could generate, and by the 1920s, southeast Michigan was getting most of its power from fossil-fuel plants along the Detroit River.

In the 1980s, Ann Arbor voters passed a millage to put the generators at Barton and Superior dams back in service. Signs and cable barriers keep watercraft away from the dams and tailraces, and horns sound a warning when water is being discharged.