When the U-M baseball field was named Ray Fisher Stadium in 1970, it honored the winningest coach in the history of Wolverine athletics. What even Fisher didn’t realize at the time was that he was still officially banned from Major League Baseball–because of the very contract squabble that had brought him to U-M in 1921.

Fisher pitched for a decade in the big leagues before quitting the Cincinnati Reds to take over as Michigan’s baseball coach (and assistant football coach) that April. By the time he stepped down in 1959, he’d won fourteen Big Ten baseball titles and an NCAA championship. As head coach, Fisher won 661 games and lost only 292–the win total a record that stood until 2000, when it was surpassed by legendary women’s softball coach Carol Hutchins.

Nineteen of Fisher’s players made it to the majors, and he recruited black players long before Jackie Robinson integrated the big leagues. Fisher twice took his squads to Japan for exhibition games that helped introduce baseball to that nation, where it remains wildly popular to this day. He also carried on a long battle with the NCAA, advocating–unsuccessfully–for the right of college ballplayers to earn money in semipro leagues over the summer. On the field he was a fighter for his players as well, renowned throughout the Big Ten for his sometimes spectacular tirades against umpires.

—

Born in 1887 on a farm in Vermont, Fisher pitched for Middlebury College and played two seasons in the minor leagues while still in college. After graduating he moved to the big leagues with the New York Highlanders–the team later renamed the Yankees. He was nicknamed “The Schoolmaster,” because during the off-season he was athletic director at Middlebury and taught Latin there.

The great Ty Cobb said Fisher, armed with a then-legal spitball, was one of his least favorite pitchers to face. He was so tough that he beat the legendary Walter Johnson, considered by many to be the greatest pitcher of all time, on the very day in 1917 that Fisher returned from a month on the disabled list with pleurisy.

After a stint in the Army in WWI, in 1918 he was acquired by the Cincinnati Reds, who promptly cut his salary nearly in half. That trade would bring him face-to-face with the scandal that changed baseball forever–and led indirectly to his banishment.

—

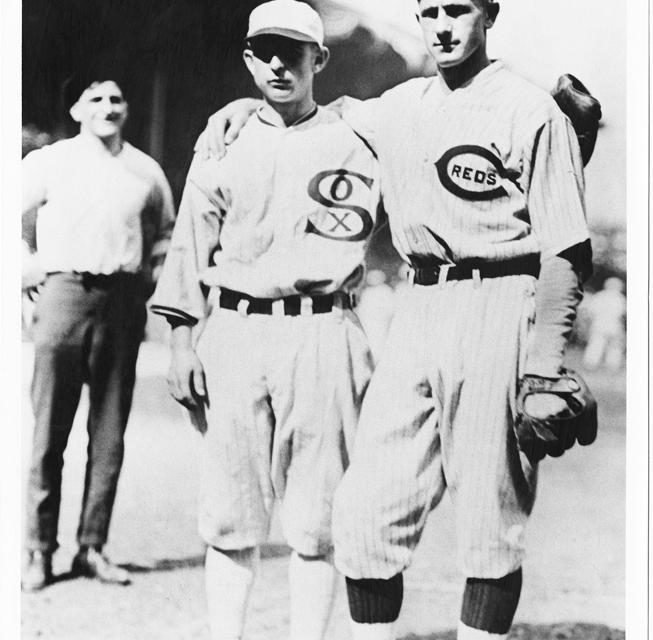

In 1919 Fisher had his best big-league season, winning fourteen games, including five shutouts, and losing only five. The World Series that year pitted the Reds against the Chicago White Sox. Fisher pitched Game Three and lost 3-0 to Sox rookie Dickey Kerr. But Cincinnati went on to win the series, and fans and writers soon started to talk about the obvious ineptitude the Chicago players had displayed.

It soon came to light that eight of the Sox had agreed with gamblers to throw the series (Kerr was one of the few not in on the fix). Major league owners, worried for the future of the sport, agreed for the first time to install a commissioner, federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, to rule the game. In 1920, Landis banned the eight “Black Sox” from baseball for life.

By then, Fisher had a young child and was exploring other options for making a living. He sought and thought he had obtained the permission of Pat Moran, the Reds manager, to interview for the coaching job at Michigan. But after he was offered the job, Moran, having examined his roster more closely and concluding he needed Fisher, changed his mind and decided to keep him. Reds owner August Herrmann offered Fisher a one-year contract with a $1,000 raise, but when he refused to sign him to a multi-year deal, Fisher took the job at U-M.

Herrmann then complained to Landis that Fisher had given only seven days’ notice of his intention to quit the team, not the contractually required ten days.

The commissioner, feeling his oats, put Fisher on the “permanent ineligible list”–one of nineteen players banned during his tenure. Ironically, one of the others was Kerr, also over a contractual dispute, in 1922.

Kerr was reinstated in 1925. Fisher remained banned, but no one at U-M cared much about that. Wolverine fans adored Fisher’s winning teams and were mightily entertained by his histrionics with umpires. Those showdowns were even less restrained in the off-season–until 1949 he coached in Vermont’s popular semipro summer league. His temper tantrums were designed mostly as showmanship and as inspiration for his players, and they so riled up opponents that in Vermont he was dubbed “Rowdy Ray” and “Cry Baby Ray” in the local press. Fisher sometimes needed police escorts to exit enemy turf after his incendiary displays turned fans into howling mobs.

Fisher finally quit Vermont baseball at age sixty-two, in mid-season during a dispute with the league commissioner over complaints he’d lodged about umpires. He continued to coach at U-M until he was seventy. Though he remained officially banned from Major League Baseball throughout his Michigan career, by then even he thought that he’d been exonerated–after all, no one in the league office objected when he served as a special spring training instructor for the Detroit Tigers and the Milwaukee Brewers in the 1960s.

—

In 1980, U-M history professor Don Proctor, after extensive research, revealed that the ban was still on the books. After receiving letters of protest–including one from president Gerald Ford, whom Fisher had coached in freshman football at U-M–major league commissioner Bowie Kuhn belatedly pronounced Fisher a “retired player in good standing.” Two years later, Fisher returned to Yankee Stadium for an Old-Timers’ Day, pushed to the pitcher’s mound in a wheelchair.

Only the oldest fans in attendance remembered him. He died a few months later, at age ninety-five, and is buried at Washtenong Memorial Park.

There’s no plaque at the stadium in the Wilpon Complex about Ray Fisher, and no official U-M biography recounts the story of his banishment. But his place in history is probably secure–who else was ever barred for nearly sixty years from the sport played in a stadium named after him?