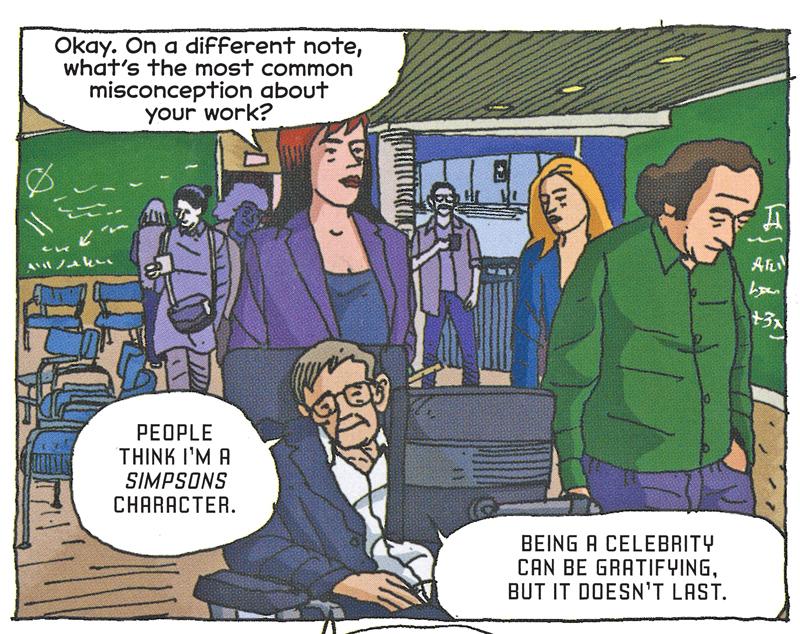

Curiosity and volunteering are how I have the good fortune to know Jim Ottaviani and his wife, Kat Hagedorn. They’re also why Jim and Kat almost got to know Stephen Hawking–and got access to Stephen’s archive, which helped Jim write a “nonfiction graphic novel” about him. The book, Hawking, illustrated by Leland Myrick, was released in July.

Jim and I met around a decade ago at 826michigan, the tutoring center hidden behind Liberty Street Robot Supply & Repair. The shop off Main St. is both an enticement and a funding mechanism for the nonprofit. Volunteers of all ages and inclinations do tutoring and encourage writing under the direction of a vigorous staff.

Volunteering there with Jim, I was intrigued by his tender and wise approach to helping high school kids with their math homework. He told me that he works at the University Library and in his spare time writes nonfiction graphic novels about science and scientists. Those offbeat books make him one of Ann Arbor’s most significant authors, though not necessarily its best known.

Jim has been an engineer, an engineering consultant, and now, he says, he “makes U-M scholarship and research available to the world” through its Deep Blue archive. And, as he is with tutoring, I’ve found him a gentle and wise friend.

—

After I learned about his books, I asked Jim if he would like to meet Stephen Hawking. This was probably a pretty silly question to ask someone with his passion for science. I knew I could probably set this up through my friends Anna Zytkow and Malcolm Perry, who were very important in Stephen’s life, and my connection to Stephen, too, through my physicist husband, Gordy.

That all worked! About five years ago, Jim and Kat and illustrator Leland Myrick set out for England. At the time, Stephen was ill and in hospital (as they say there). So Stephen’s capable and caring personal assistant and gatekeeper, Judith Croasdell, took over, for which Jim is grateful (as are the many other people Croasdell aided during her years with Stephen).

She arranged for Jim to see Stephen’s papers, photos, and memorabilia. These are stored in what Jim describes as a cramped closet in Cambridge University’s science library. “It’s totally unorganized. Box on box. Binders without labels. There were so many treasures in there,” he recalls. “Just exploring the beauty in there is good and meaningful.”

Fortunately, his work at the U-M had accustomed him to this kind of disorganized collection. He even once sorted a donation of part of Orson Welles’ “War of the Worlds” archives.

Stephen’s archive included “beautiful, beautiful photographs,” Jim says. “There is one of his hands that’s amazing.” Myrick included drawings of Stephen’s hands throughout their book.

When Judith asked, “Would you like to see Stephen’s house?” the answer again was obvious. Jim even lay down on Stephen’s bed. A polite “midwestern boy,” he says he felt like he was intruding when he did that–but it let him see the view out the window. That led to the image at the end of Hawking: a dark sky and Stephen floating freely among stars–where, instead of mythical figures, he sees mathematical diagrams.

When I thumbed through the book after Jim told me about his experiences in England, I was touched to realize that it’s not a construction imagined by Jim. It’s really a reconstruction of Stephen’s life through artifacts, research, and conversations.

“How do you deal with all that material?” I asked him. “I get a headache,” he said with his usual self-deprecating grin. It’s a big grin, which stands out even more in contrast to his balding head and modest, middle-aged demeanor.

He digests his research material slowly, learning as he goes along. And then comes the critical thing–remembering how he felt before he understood the life and the science. He needs to reclaim that innocence to make the book fit the experience of the reader.

“It’s not really a conscious process,” he says, struggling to explain. “It’s a matter of envisioning what the character is going to say, and what the artist is going to draw. It’s trying to show what the person feels when they are saying that.”

That’s also why he uses images as well as words to convey the beauty he finds in science and its practitioners. Nonfiction graphic novel “is an unfortunate name for the kind of thing I do,” he says. “But words and pictures are an effective form of communication.”

As an engineer, he did a lot of envisioning. As a librarian he works with words. As both he worked with research. Perhaps that’s a perfect background for making visual books.

“I often think simultaneously in images and words,” he agrees. “It’s a process of discovery as you go along.”

He works with several different artists and says they communicate a lot even about very fine points. They also sometimes argue about which is the best way to illustrate something. He says the story is the winner in this process, because the back-and-forth makes it better.

As if mimicking his books, or vice versa, he’s an animated talker, gesticulating and using body language and his expressively mobile face. To me it’s a perfect example of artists and their work as a unified whole.

—

Breaking into publishing is notoriously difficult, so in 1996 Jim established his own publishing company, General Tektonics Labs, chosen as an allusion to the place where Peter Parker became Spiderman (he later shortened the name to G.T. Labs). “It was a get-rich-slow scheme,” he says. He paid the artists and printers for his early books out of his own pocket. It was thirteen years before he could pay those expenses out of royalties instead.

But a dozen self-published books provided him with “proof of concept,” and with the market for graphic books expanding, he finally landed an agent and then a big publisher. His 2013 book with Myrick, on physicist Richard Feynman, was a New York Times best seller. Volumes on women in space and biologist E.O. Wilson are in the works.

He writes his books after work, when he might otherwise be running, bicycling, or kayaking. “What if I found out it was bad for me–would I stop?” he asks himself.

“I don’t think so,” he answers, flashing that big grin.