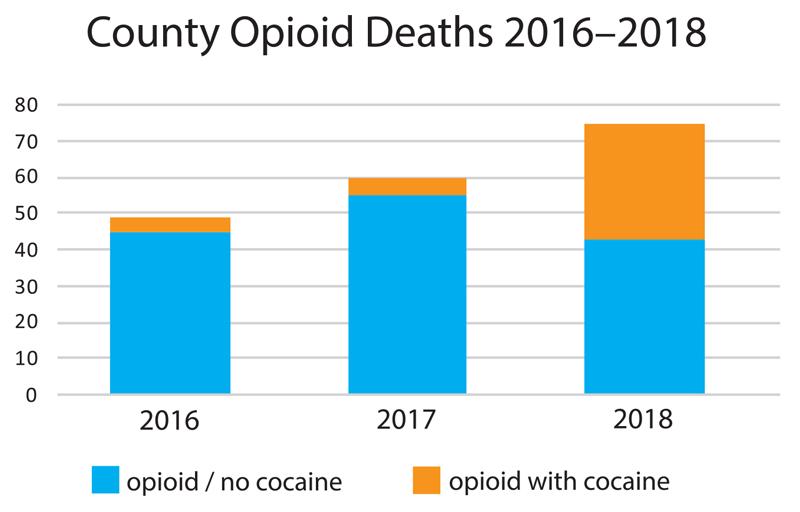

Opioids killed more people in Washtenaw County than ever in 2018. Seventy-five county residents died of overdoses last year, up from sixty in 2017 and forty-nine in 2016 (see chart).

Most of those deaths involved fentanyl, a synthetic opioid fifty to 100 times more potent than heroin. Dealers add it to other drugs to increase their potency, but even a slight miscalculation can be fatal.

Most deaths in recent years have involved heroin laced with fentanyl, but now cocaine is driving the increase. Thirty-two of the county’s opioid deaths involved cocaine last year–compared to four in 2016 and five in 2017.

“People use cocaine thinking that might be a safer drug” says deputy county health officer Jimena Loveluck. But what’s being sold as cocaine is far deadlier than it used to be. “Dealers are purposely lacing cocaine and other drugs, such as methamphetamine, counterfeit Xanax and oxycodone, with fentanyl and carfentanil,” emails county epidemiologist Adreanne Waller. “The Washtenaw County Medical Examiner has suggested that users are unwittingly using cocaine not knowing that it includes fentanyl.”

“It’s happening with all kinds of drugs,” adds Loveluck. “We’re seeing a multidrug epidemic.”

“Fentanyl is much cheaper than heroin,” Waller explains. “It’s much easier to move because the volume required for the dosages are much smaller. It also seems to accelerate the addiction process. From a business model, even though many of your customers die, you still are producing more and more demand. People are now looking specifically for fentanyl.”

Whether they take it knowingly or not, fentanyl users are much more likely to overdose–and harder to save when they do. Naloxone, an “opioid antagonist,” now widely carried by paramedics and law enforcement, can quickly revive people who’ve overdosed–but it’s less effective when they’ve taken fentanyl.

“If we get there quickly, one [Naloxone] dose in five minutes should do it,” says Huron Valley Ambulance spokesperson Matt Rose. “A second dose is used if they’ve taken mixed drugs.”

“If there’s an overdose involving fentanyl, it often takes more than one dose of Naloxone to revive someone,” concurs Loveluck. “If they can be revived at all.”

Waller warns Naloxone is no magic bullet. “A true solution has to involve multilevel interventions: from policy to education to law enforcement.” That’s the goal of the Washtenaw Health Initiative Opioid Project, which, Loveluck says, “brings together key stakeholders to share information to formulate a coordinated response.” Members are now finalizing a two-year action plan that, she emails, will “include communication tools for providers, promoting pain management options that are an alternative to opioids, greater community education and addressing stigma and providing tools to help navigate resources for substance use disorder treatment and support for family members/loved ones.”

In addition, Loveluck says, “several new initiatives are starting to expand recovery housing options, expand medication assisted treatment [and] focus on specific populations like pregnant women and youth.”

Loveluck also points to a new local chapter of Families Against Narcotics (FAN). In addition to supporting users’ families, their monthly meetings at the 2|42 Community Church on Wagner Rd. are a source of Naloxone kits.

—

This article has been edited since it was published in the March 2019 Ann Arbor Observer. The sponsorship of the Opioid Project has been corrected.