It was not till 1870, more than fifty years after the U-M’s founding in 1817, that it first admitted female students, beginning what some regents of the time termed “a dangerous experiment.” In February, as part of the U-M’s bicentennial celebrations, the LS&A’s Residential College will present A Dangerous Experiment, a play written by Emma McGlashen, a junior majoring in English and drama, that tells the story of those first women students. Collaborating with McGlashen on researching and writing the play were fellow student Catherine Audette and Kate Mendeloff, the RC lecturer who directs the popular Shakespeare in the Arb productions every summer.

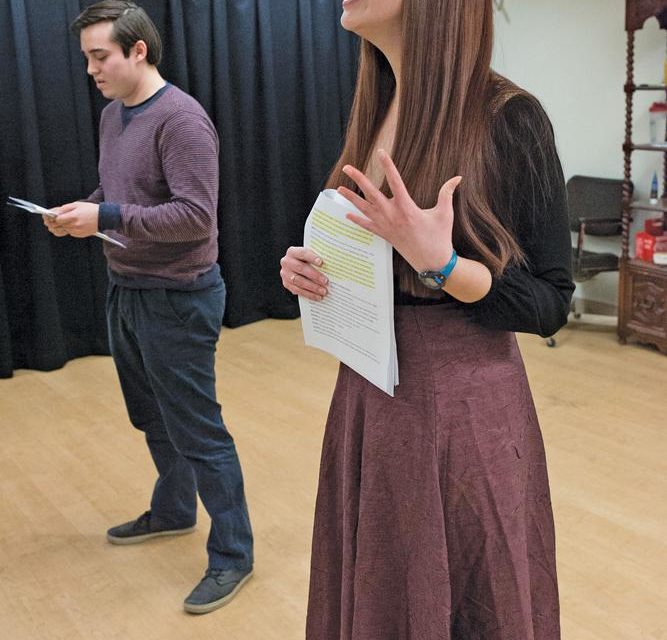

The play follows five women–each a fictionalized amalgam of several of the actual thirty-four women in that first class–on their pioneering journey, starting with their arrival at Ann Arbor’s train station in the fall of 1870. Watching some early rehearsals, I was moved by the production’s depictions of the rejection, ridicule, and open hostility the women faced at every turn: when trying to rent rooms in boarding houses, in the blatantly unequal treatment they experienced while taking their entrance exams, and with the artificial limitations placed on their learning in classrooms, such as being denied equal access to cadavers in anatomy class.

The longer I watched, the more the play brought up for me memories of another struggle for human rights, the civil rights movement. When, in A Dangerous Experiment, two women face verbal harassment and physical intimidation in a street encounter with several male students, I was reminded of the similar, though often far more vicious, encounters African Americans faced while attempting to integrate some schools and colleges in the South in the 1950s and ’60s. And watching one of the scenes, an academic debate in which a male character spouts some pseudoscience to justify denying women equal access to higher education, I was reminded of similar arguments used to rationalize racism in the U.S. and anti-Semitism by the Nazis.

Happily, the play also shows more enlightened attitudes and actions, such as when U-M president James Angell allows an otherwise qualified young woman to be admitted on probation while she brings her Latin proficiency up to the standard required on the entrance exam. Watching the actors, most of them current students, I was often aware that the power of the play is amplified by the fact that their lives as students are at once similar and of course quite different from their stage roles.

The play’s sets are spare, but the actors perform in full period costumes, and the play’s language is an effective meld of nineteenth- and twentieth-century vernacular. “We wanted to capture the feeling of contemporary humanity while retaining the elevated nature of Victorian speech,” says McGlashen.

A Dangerous Experiment is not only a worthwhile reminder of an important watershed moment in the history of the U-M and of women’s rights in general, but also a timely opportunity to reflect on our present-day blind spots regarding equal rights for everyone.

The play runs February 10-12.