In the early years of the U-M School of Medicine, Gregor Nagele was a legend. Dean Victor Vaughan described him as a “most proficient anatomist and there is no artery or nerve described by Gray, which Nagele could not find and trace to its final termination.” Students would sometimes place a knife on a cadaver, and Nagele would describe everything it would penetrate if pushed through. His position at the university: janitor.

Born in Wittenberg, Germany, in 1821, Nagele and his wife emigrated in 1848. In February of that year, they walked from Buffalo to Ann Arbor–because, Nagele later explained, Lake Erie was frozen “so the ships could not go” and “the stage [coach] cost too much.”

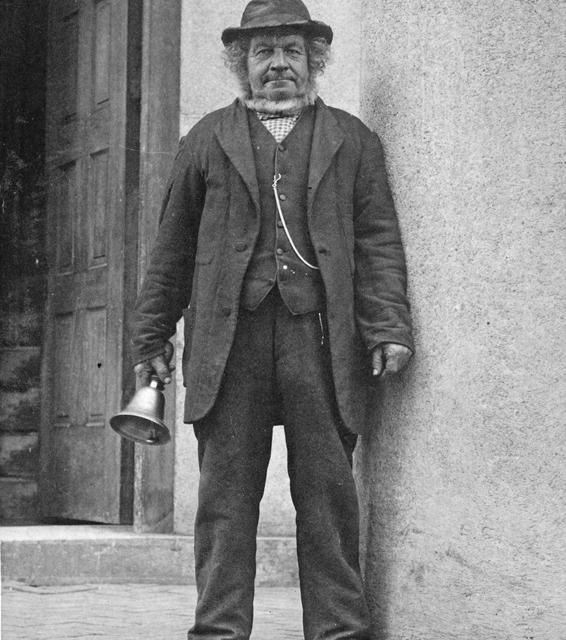

Working for masons Mount & Ferry, he helped dig the basement for the med school’s first building. Then he carried the bricks to build the walls. When the school opened in 1850, he was employed as the janitor, where his duties included ringing a dinner bell from the front steps to summon the students to class. He was, Vaughan wrote, “kind hearted, genial in manner, true to his duty, and beloved by all who came in contact with him.”

Nagele picked up a good part of his proficiency in anatomy from Corydon La Ford, who was hired as professor of anatomy in 1854 and taught the subject for forty years. A cautious man who feared nothing more than being wrong, Ford carefully prepared for each class and often worked on his dissections late into the night. Nagele stayed with Ford as he did so, and the professor liked to teach as he worked.

“Years of this association with Professor Ford made Nagele extremely proficient in identifying most parts of the body, and he was frequently called on by the students to help them with their dissection,” writes Donald Huelke in The History of the Department of Anatomy (1961). In the practical anatomy laboratory he became far superior to most demonstrators of anatomy in identifying body parts (except for the brain–“that was too much for me,” he’d say). Recognizing his prowess, the students affectionately called him “Doc.”

—

In Nagele’s day, a major problem for medical schools was procuring cadavers for dissection. That responsibility fell to the Demonstrator of Anatomy, who found the duties to be peculiar. “The chief end of my official existence was to buy, steal, dig up, or in any other manner procure subjects for the dissecting room,” recalled Edmund Andrews in 1901. “To instruct the students was deemed meritorious, if I could get the time for it, but by no means as important as getting the subjects [for dissection]. Then the law was peculiar. I was a state officer charged with the duty of getting the material, but there was a statute consigning me to prison if I did my duty.”

Enraged by reports of grave robbing, mobs sometimes stormed medical schools to reclaim their loved ones. To prevent this at Michigan, Andrews wrote, “I allowed no cadaver to be exhumed in Ann Arbor in any circumstances.” Instead, the School of Medicine developed a network of distant suppliers and arranged for deliveries to arrive at night. The job of receiving these deliveries fell to Nagele, who was said to have cared for more than 2,000 cadavers over the years.

According to a Michigan Daily article in 1900, “Dr. Nagele always claimed never to have participated in these disturbances of the cemetery graves, but he never denied that he was always ready in the name of science to accept any material upon which he could use his dissecting blade. These efforts of his to obtain subjects for dissection forced him to appear several times upon the witness stand, but he always managed to save himself from trouble on these occasions by denying any knowledge of the English language.”

—

After forty-seven years with the university, the Board of Regents decided Nagele was no longer needed. By then he was too old and feeble for janitorial work, and, with the university clock tolling the hours, his handbell was no longer needed.

According to Vaughan, Nagele came to him and with tears in his eyes said, “They tell me that I can no longer ring the bell, and that I am discharged.”

Suddenly, every member of the department was infected with a strange illness. None of them could hear the university clock, but they could hear Nagele’s bell. The Board of Regents relented, and Nagele continued to ring his bell for the rest of his life. The members of the medical faculty provided him a pension of $10 a month.

In June 1900, Nagele completed fifty years of service to the university. In all those years, he had missed only two days of work. He died a month later after a brief illness.

The Michigan Daily shared the news with students when they returned to school that September.

“It is safe to say,” the article concluded, “that had the old man died during the college year the department would have closed its doors for a day and the medical students attended his funeral in a body.”