In January 2017, my wife Andrea and I purchased an old Greek Revival home at 1418 Broadway. Years earlier, I’d researched this house for the new edition of Historic Ann Arbor: An Architectural Guide, which I cowrote with Susan Wineberg. It was built by Absolom Traver in the 1830s or 1840s. But I could find very little information on Traver.

This was odd, since Traver’s name is everywhere in northeast Ann Arbor–Traver Road, Traver Creek, Traver Village Shopping Center, Traver Crossing Apartments, Traver Knoll Apartments, Traverwood Library, and on and on. Yet so little is known about him that one history calls him “Augustus Traver.” The announcement of the Traverwood Library said it was named after a “George Traver Sr.”

I was determined to find out more. Using techniques I picked up while writing the book and researching my own genealogy, I located Absolom’s descendants, who generously shared historical documentation and family stories.

George Traver Sr., it turns out, was Absolom’s son. His reminiscences, set down in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, traced Absolom’s path from Manhattan tavern keeper to Ann Arbor farmer, miller, and neighborhood developer.

Absolom Traver was born September 29, 1800, on Governors Island, New York, to parents Catherine and Frederick Traver. A record from 1812 has the family living in the Five Points neighborhood of Manhattan. “Five Points,” an 1827 painting by George Catlin, shows the neighborhood during the Travers’ time–animals running wild, prostitutes leaning out of windows, fights breaking out in the streets, people of different races and classes mixing freely, and a “grocery” on every corner. In early nineteenth century New York, “groceries” were just unsavory gin houses.

In the 1819 NYC common council minutes, Traver is listed as chief of Fire Engine Company No. 40. Though still a teenager, he was also running a “grocery” below the family’s residence at 226 Mulberry St. Traver had co-founded the celebrated Engine Company No. 40, whose white and gilded fire engine was known as “Lady Washington” or “The White Ghost.” Life in these engine companies was rough and rowdy as rival companies brawled over bounties and turf.

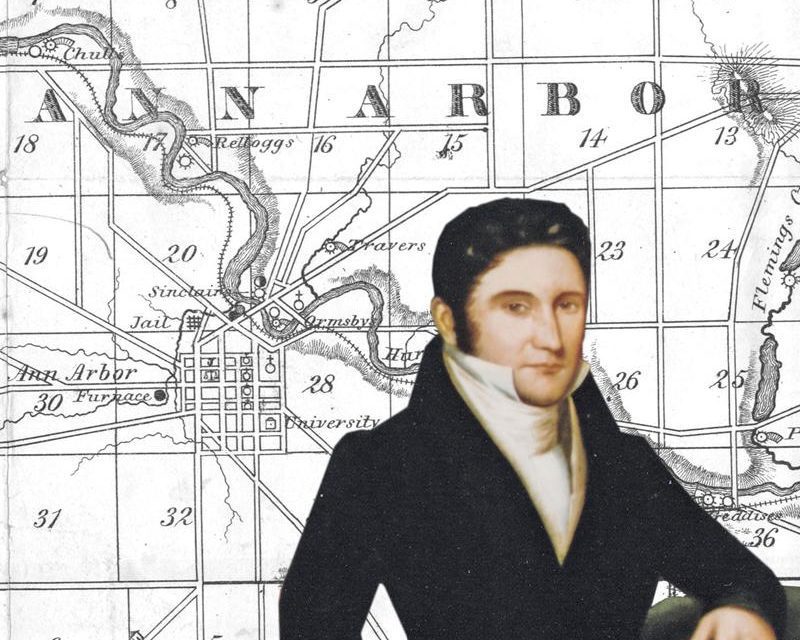

In 1825, Absolom married Charlotte Miller of Boston. Fine portraits in the possession of descendant Debbie Delong capture an image of the young couple shortly after their marriage. I tracked down Delong and her cousin Herb Miller through online genealogy forums. Both were extremely helpful, and shared vast amounts of biographical information, pictures, and family lore.

In the summer of 1830, Traver and a friend, Hay Stephenson, boarded a steamboat for Albany. From there they walked to Buffalo then crossed into Canada and continued their epic walk to Detroit, finally following a series of rough roads and Indian trails to the burgeoning frontier village of Ann Arbor.

—

Though founded by John Allen and Elisha Walker Rumsey just six years earlier, Ann Arbor already had more than 1,000 residents. George Traver recalled the advice his father was given by a New York neighbor: “Now Absolom, you were born and brought up in the city and know nothing about choosing good land, if you want a good farm choose land on which is good thrifty timber and plenty of running water.” Traver passed up the land where the U-M Central Campus now stands because the timber was scrubby. Instead, for $1,000, he purchased 178 acres in Section 21 of what was then Ann Arbor Township. The land was covered with substantial virgin forest and had a creek running through it that was sufficient to drive a water wheel. There were also freshwater springs and three well-worn Indian trails. After securing his future homesite, Traver made the long walk back to New York before winter hit.

In early May 1833, Absolom and a very pregnant Charlotte packed up their five children and all their possessions and boarded a Hudson River steamboat to Albany. From there they took an Erie Canal flatboat to Buffalo, and a Lake Erie steamer to Detroit. Charlotte gave birth to their sixth child, Jane, on board.

Much had changed in Lower Town since Absolom was last there in 1830. New Yorkers Anson Brown and Edward Fuller had subdivided land along the river, ambitiously naming the streets after those in Manhattan: Broadway, Wall, and Maiden Lane. In 1831, Brown and Asa Smith had built two substantial brick buildings on Broadway. Still standing at 1001 Broadway is Ann Arbor’s oldest surviving commercial building. The Washtenaw House Hotel, built the same year, was known as the finest stagecoach stop between Detroit and Chicago. For a brief period, this new “Lower Town” would rival the original “Upper Village” as the center of Ann Arbor.

Traver immediately began construction of a frame house, which still stands today at 1309 Jones Drive. That house had always piqued my interest. Though obscured by vinyl siding, the outline and shape of the home speak to a very early Greek Revival residence.

In our book, we called it the David Lesure House, after a Traver relative who bought it in 1840. Over months of walking by it with my dog, I kept asking Wineberg if it might have been Traver’s first house. Finally she remembered a note she had made more than ten years earlier. In a barely legible legal description conveying a series of lots on Jones Drive in 1866, she had circled “also the right of conveying the water from a spring near said Traver’s old house.” Voila!

The Jones Dr. house lies much lower on the Broadway hill than Absolom’s later home at 1418 Broadway–the street wasn’t extended to the hilltop until 1837. This section of Jones Dr. is much older–it appears to follow one of the Indian trails.

“Michigan Fever” was in its early stages, and Traver was set to take advantage of the boom. In 1834, he built a water-powered sawmill near where Jones Dr. and Plymouth meet today. By late 1837, he subdivided part of his farmland along Broadway and Jones as “Traver’s Addition” to the village.

By then, though, the nation was in the grip of the Panic of 1837. With banks failing and land prices plummeting, lots in Traver’s Addition sold slowly. His sawmill milled the lumber for the original U-M buildings in 1839, but as the city’s center of gravity shifted toward the university, Lower Town would never again rival the Upper Village.

George Traver recalled that slabs of wood from the sawmill were fashioned into benches for the students in the area’s first school, held in the upstairs of the farmhouse on Jones Dr. In 1837, with the help of a carpenter friend from back east, Traver built a small frame schoolhouse on Maiden Lane. An article in “Michigan Farmer Vol. 11” in 1853 calls Traver an “industrious farmer” and discusses his techniques for breaking large boulders and draining his low, wet land. But others did the heavy work of plowing–apparently the city boy never mastered the skills needed to work with oxen. “My father farmed it for twenty years, but never did a day’s work with a team; he never wanted anything to do with a team,” George recalled. “So as soon as I got old enough to hold the lines I had to learn to drive.”

Other Traver relatives joined the family in Ann Arbor, including Absolom’s parents Frederick and Catherine, who lived with the family on Jones. Herb Miller told me a family story: “The children loved their grandmother dearly and would visit her in her room. But the grandfather was a mean-spirited S.O.B., and, when they would hear his cane on the porch as he approached the room, they would all scramble out the back window so he would not catch them there.”

Catherine lived with her son until her death in 1860 at the age of ninety-three. Frederick Traver died in 1840, the year Absolom sold the farmhouse on Jones and moved to Broadway. There he built two Greek Revival homes–our house at 1418 and a larger house at 1300 Broadway. 1418 Broadway may have been built first, and after 1845 became the home of daughter Mary Ann and her husband Apollos A. Tuttle. In the 1840s and 1850s, Traver Rd. was sometimes called Tuttle’s Rd.

Charlotte Traver died in March 1846 at the age of forty-two. In September Absolom married Amanda M. Hill in the Unitarian Church. Amanda took on the daunting task of helping to raise Absolom and Charlotte’s by-then nine children; over the next eight years she would give birth to three more.

The Traver children were put to work at an early age. In addition to the farm, the sawmill needed to be run, and in the late 1850s, Traver built a grist mill on Traver Creek, next to his 1300 Broadway house. George Traver recalled, “I never could go to school except for a short time in the winter, and when I was 17, I had to give up school for good.” In 1856, Absolom platted Traver’s Second Addition along Maiden Lane.

Three of Absolom’s sons volunteered to fight for the Union during the Civil War, along with son-in-law Tuttle, who with Alonzo Traver likely saw the most action as members of Michigan’s distinguished Twentieth Infantry Division. Son Robert C. was a regimental tuba player in the Fifteenth Michigan Infantry; George served primarily in the western theater, in the Sixth Infantry. Though all survived the war, other neighbors weren’t so lucky. Lower Town had the highest number of enlistments of any part of Ann Arbor, and forty-one men from the neighborhood died in the Civil War. Their names are inscribed on a monument in Fairview Cemetery off Pontiac Trail.

—

Absolom Traver died at his home on August 12, 1869. In the papers, only a small notice marked his passing. The remaining Traver family would soon leave Ann Arbor for Milan, Saline, Jackson, and Hillsdale. As was true of many early Ann Arbor pioneers, few remained in town to record Traver’s legacy when the local histories were written.

In the nearly 150 years since Absolom Traver’s death, the neighborhood that he shaped has changed significantly. The 1879 ToledoAnn Arbor Railroad, and the 1925 Plymouth Road bypass of Broadway hill, changed the natural landscape forever. The Leslie Science & Nature Center now occupies the northern part of Traver’s old farm, along with homes and apartments from the 1950s and 1960s along Traver Rd. and Barton Dr. Apartments and condos line his land on Maiden Lane and Island Dr. Sadly, his home at 1300 Broadway was razed in 2006, but that led to the neighborhood receiving historic district protection in 2008.

If you look hard enough, though, remnants of this very different time still remain. The roads in Traver’s two subdivisions still follow the map that he laid out. Many of the homes that he and his neighbors built, with wood from his sawmill, still stand. And Traver Creek still winds gently through the neighborhood.

Hi Patrick,

Thanks so much for a wonderful article!!! Absolom is my 4th great grandfather 🙂

Daryl Traver

Absalom was also my 4th grandfather. Michael Hunter, Athens, Ohio

The family tree available to me doesn’t reach as far back as Absolom, but I know Ella Traver, wife of Charles Porter Wood, as my great grandmother and namesake. Nice to learn more detail about the “family farm” as it was described to me as a child.

Thanks for your article. I have a house next to Traver Creek. For years I’ve wondered how the name Traver came to be associated with so many places in AA.

Thanks so much for this very interesting article. The Zahn family moved to 1300 Broadway in 1919. Nine Zahn children lived to adulthood. My grandfather, Christian, died in 1938 and grandmother Pauline died in 1960. An article in AA News stated that due to foundation problems, it had to be torn down. Per Zillow, the replacement house was built in 2006. It looks very similar to the original, and I am sure the family would be pleased. It is being used for student rentals.

What an interesting article! Absolom and Charlotte were my 3rd great grandparents. Their son, George, was my 2nd great grandfather. And Herb Miller, mentioned in this article, was my dad who we lost in 2020. He so enjoyed researching his Traver roots.